“Da natural vaghezza mosso”: Giovanni Francesco Gemelli Careri’s Travels Through Armenia (1694)

Abstract Travel Literature is a goldmine of information for the study of Armenian art and culture. Nevertheless, it is a largely unexplored field of investigation, especially accounts written in Italian. Among the understudied works, Giro del mondo (1699‑1700) by Giovanni Francesco Gemelli Careri (1651‑1724) stands out. Travelling to Ispahan across Historical Armenia in 1694, Gemelli described populations, settlements, and monuments. The analysis retraces the traveller’s path examining the information on the presence and conditions of the Armenian artistic heritage in the Eastern Ottoman districts and the Safavid provinces of Erevan and Naxiǰevan.

Keywords Armenian art. Travel literature. Giovanni Francesco Gemelli Careri. Ottoman Empire. Safavid Empire. Erzurum. Kars. T‘alin. Ēǰmiacin. Erevan. Gełard. Naxiǰevan. J̌ułay.

1 European Travel Literature: A Source for Armenian Art History

Since the dawn of civilisation, travels have been part of the human experience in response to dangers, necessity, or even the pure desire for knowledge. They constitute a fertile soil for humanistic studies thanks to the accounts of those who entrusted their memory to posterity through writing. Despite the long-standing fascination with travel literature and the extensive studies devoted to it, the field is still far from being fully explored. This is due to the vast quantity of material to be examined and the inevitable language barriers associated with it.1

This paper is the result of research conducted with the financial support of the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research and the intellectual and moral support of Marc Mamigonian, to whom I express my gratitude. I would also like to thank Dr. Roberto Rabbia and Prof. Patricia Stirnemann for proofreading the English text. Furthermore, my gratitude extends to the anonymous referees whose advice led to improvements to the article.

1 From the purely historical perspective, the period most extensively studied to date continues to be the Middle Ages; in contrast, studies of the Modern and Contemporary Ages tend to adopt either a monographic or anthological approach, cf. Guglielminetti 1967; Searight 1979; Berchet 1985; Reichert 1992; Menestò 1993; Invernizzi 2001; Surdich 2017. However, recent progress in the field of mobilities turn research can provide new insights and methodological tools to the disciplines of humanistic sciences, cf. Urry 2007; Adey et al. 2014; Merriman, Pearce 2017; Biasiori, Mazzini, Rabbiosi 2023; Nelles, Salzberg 2023; Holmberg 2024.

A promising line of research combines art history and odeporic, i.e. the use of travel literature as a source for the study of artistic heritage. This approach is highly significant for Armenian art, whose numerous samples only represent the remnants of a much more glorious past.2 Considering natural disasters, neglect and deliberate destructions, the voices of wayfarers from the past can help to understand (and sometimes to reconstruct) what was once the ancient consistency of a cultural heritage sadly heavily threatened to this day (Ferrari 2019, 11‑32; Dorfmann-Lazarev, Khatchadourian 2023).

2 If only a tiny percentage of the art of medieval Byzantium remains today, the situation of Armenian art is far worse, cf. Demus 2008, 5.

However, this is still a relatively unexplored area of research, apart from the monographs dedicated to the most famous sites (e.g. Grigoryan 2015; Kéfélian 2021), works conceived with an avowedly Armenian focus (Lynch 1901) or dedicated to Near Eastern antiquities, in which the description of Armenian monuments is relegated to the background compared to other contexts.3 To this day, there is no comprehensive and critically updated documentation on Armenia and its artistic production, even less so related to European travel literature.4

3 E.g. Chardin 1711; Ker Porter 1821; Layard 1853; cf. Invernizzi 2005, VII-XIII.

4 Previous studies have predominantly referenced renowned travel accounts, from Marco Polo to Henry Lynch, in a more descriptive than analytical perspective, e.g. Karagezjan 2019. It is beyond doubt that the French jeweller and traveller Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (1605‑89) is among the most frequently cited authors in Armenia studies. Like the younger Jean Chardin (1643‑1713), Tavernier undertook business voyages through its regions, and his account provides useful insights into the commercial mobility of the period; however, it lacks references to artistic and historical matters, and is full of inaccuracies and far-fetched anecdotes, which have been disproved or ridiculed by subsequent writers, e.g. Gemelli 2: 17. Among the Italian travel-writers of the seventeenth century, Ambrogio Bembo (1652‑1705) and Nicolò Manucci (1638‑1717) are worthy of note. For further information, cf. Pedrini 2011, Invernizzi 2012 and the related bibliography.

This paper aims to fill the gaps of a mosaic that is as complex as it is essential to the understanding of Armenian culture and its perception, possibly expanding the still ill-defined boundaries of its frame. To this purpose a travel report scarcely known in Armenian studies will be analysed, of which exists no critical edition (not even in Italian, the language it was written in). The author of the account is Giovanni Francesco Gemelli Careri (1651‑1724), one of the first Italians to undertake an around-the-world voyage for sheer pleasure.5

5 Gemelli 1699, vols 1 and 2. There are only a few studies on this author and his works, and the most specific ones concerning mostly travels to the Far East and the Americas, which are beyond the scope of the present discussion. This is a selected and updated list of such studies: Du Halde 1722, XIV-XVIII; Prevost 1753, 465; Grossi 1820; Ciampi 1859; De Gubernatis 1875, 57‑8; Amat di S. Filippo, 467‑70; Ghirlanda 1899; Magnaghi 1900; Nunnari 1901; Zeri 1904; Vece 1906; Croce 1929, 106; Magnaghi 1932; Barthold 1947, 139; de Vargas 1955; Guglielminetti 1967, 683‑4; Zoli 1972, 409‑16; Perocco 1985, 144‑65; Fatica 1998; Galeota 1994; Buccini 1996; Ballo Alagna 1997; Maccarone-Amuso 2000; Doria 2000; Negro Spina 2001; Invernizzi 2005, 387‑91; Hester 2008, 155 ff.; Sarzi Amade 2012.

2 An Unexplored Case: Giovanni Francesco Gemelli Careri and His Chronicle Around the (Armenian) World

When the first volume of his Giro del Mondo went to press in 1699, Gemelli was 48 years old, which means he was born in 1651 (Gemelli 1: 2) [fig. 1].6 Born in Radicena (Calabria), he was educated in Naples at the Jesuit Fathers College. Having obtained a degree in utroque iure, he was allowed to hold positions in the administration of the viceroyalty of Naples between 1671 and 1685. Being allegedly prevented from exercising his duties by serious disagreements with shady personalities,7 he left his post to undertake a journey through Europe (from 1685 to 1687), during which he participated in the Hungarian campaigns against the Ottoman Empire, both being wounded (Battle of Buda, 2 September 1686) and receiving commendations for military prowess (Battle of Mohács, 12 August 1687). These awards guaranteed him reinstatement in the viceroyalty administration, but only for four years. Between 1689 and 1693, he worked as auditor at the magistracies of Lecce and L’Aquila. In those years, he published two travel reports, Relazione delle campagne d’Ungheria (1689) and Viaggi per l’Europa (1693) (Doria 2000, 43).

6 In fact, some claim that Gemini was born in 1648, cf. Fatica 1998, 66.

7 In explaining his motivations for travelling, the author speaks about “unfair persecutions and undue outrages”, Gemelli 1: 2‑3. Translations from Italian are by the author of this article.

Figure 1 Portrait of Giovanni Francesco Gemelli Careri, 1699, Giro del mondo, 1, frontispiece

Once again victim of alleged harassment by his detractors, he decided to leave Naples and, notebook in hand, set off on a new, longer journey. The original plan to visit the Chinese Empire underwent a gradual expansion that in five and a half years (13 June 1693‑4 December 1698) took him from Egypt to the Indies, then from China to the Philippines, where he sailed for Mexico and from there came back to Europe. After his return, he gained international fame by publishing the six-volume detailed account of his wanderings, entitled Giro del Mondo (Around the World, 1699‑1700). The work was reprinted at least seven times between 1699 and 1728, and was translated into French (1719), and English (1732), while excerpts from it were included in foreign compilations, including German and Russians works (Doria 2000, 44; Invernizzi 2005, 387). After his return to his homeland, perhaps due in part to his literary success, Gemelli was appointed vicar judge and auditor of the navy. He died in Naples on 25 July 1724.

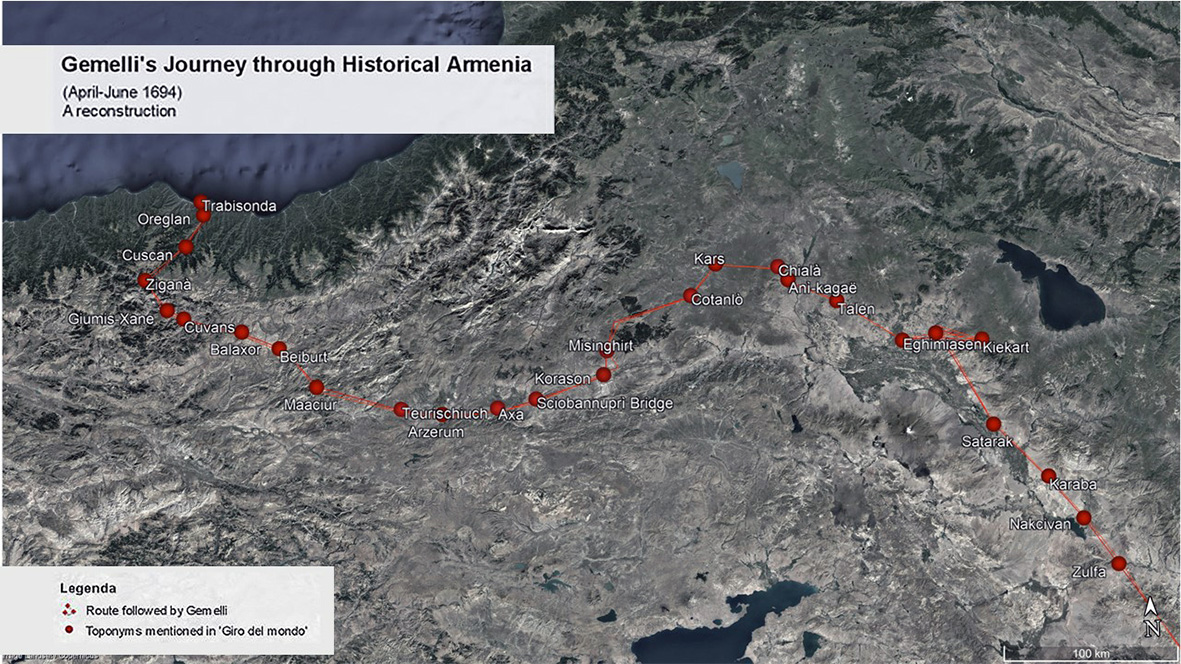

Apart from the editorial history and the critical success of the Giro, what is important to us is its relevance as a source for the study of Armenian art and culture in a period characterised by constant clashes between the Ottoman and Safavid Empires. Thus, an annotated reconstruction of the traveller’s path through historical Armenia is proposed here. At the same time, the Mediterranean area is excluded, not for lack of evidence of Armenian presence – significant in the districts of Edirne,8 Smirne9 and Jerusalem10 –, but because it would deserve a separate discussion. The itinerary analysed and reconstructed is that from Trebizond to J̌ułay [fig. 2], described in the first two volumes of his monumental report, dedicated respectively to Giro del Mondo del Dottor D. Giovanni Francesco Gemelli Careri contenente le cose più ragguardevoli vedute nella Turchia/Persia (The Most Remarkable Things Seen in Turkey and Persia) (Gemelli 1: 395‑450, 2: 1‑22).

8 Between 22 December 1693 and 4 January 1694, Gemelli stayed in Adrianople, “inhabited by Greeks, Jews, Armenians, Turks, Wallachians, and other nations” (Gemelli 1: 242‑89, in particular 244). The author also mentions the existence of an Armenian community in Malgarà (i.e. Malkara), cf. Gemelli 1: 240.

9 Gemelli stayed twice in Izmir: from 27 November to 12 December 1693 and from 17 February to 9 March 1694 (cf. Gemelli 1: 213‑24, 342‑50). He also reports that, on the latter occasion, he lodged at the Armenian caravanserai because, in his opinion, the Armenians “though schismatics, have no such aversion; on the contrary, they lovingly procure to render every possible service to Catholics on occasion, as I have experienced many times” (Gemelli 1: 343). The Greeks, on the other hand, are thought by Gemelli to be fraudulent and unfriendly to Catholics.

10 During his stay in Jerusalem (29 August-8 September 1693), Gemelli described the St. James complex, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the tomb of the Virgin, a small Armenian church on Mount Zion and other places of worship attended (also) by Armenians (cf. Gemelli 1: 111‑78).

Figure 2 Reconstruction of Gemelli Careri’s travel through Armenia (1694). Author’s elaboration

Having left Naples on 13 June 1693, Gemelli stopped in Redicina to bid farewell to his brother, Abbot Giovanni Battista. He left for Messina on 7 July11 and, within six months, he visited Malta,12 Egypt,13 the Holy Land, then, via the Aegean islands,14 Izmir, Gallipoli,15 and Edirne, where he also saw Sultan Ahmed II (Gemelli 1: 6‑402). He then reached Constantinople on 10 January 1694, where he remained until 11 April.16 During these three months, a series of worrisome accidents occurred, including Gemelli’s arrest by the Ottoman authorities, just before his planned departure for Trebizond, on suspicion of being a spy (Gemelli 1: 292‑336, 369‑402).17 The traveller had previous misadventures with Ottoman guards and janissaries, which contributed to eliciting antipathy towards the Turks that, with rare exceptions,18 made his stay within their domains rather unpleasant.19

11 He arrived in Radicena on 27 June and left from Palmi on 7 July 1963.

12 The Italian traveller stopped in Malta from 15 to 21 July.

13 Gemelli was in Egypt from 1 to 23 August 1693, then from 2 to 10 October, mainly in Alexandria and Cairo.

14 Specifically, he called at Rhodes (24 October-11 November 1693), Stanchio (Coo, 13‑14 November 1693), Scio (Chios, 17 November 1693) and, after passing Smyrna (cf. fn. 9), Mitylene (Lesvos port, 13‑15 December 1693) and Tenedos (today’s Bozcaada, 15‑17 December 1693).

15 He stayed in Gallipoli for just two days (17‑19 December 1693).

16 Gemelli also stayed twice in the Ottoman capital: from 10 to 28 January, then from 29 March to 11 April 1694.

17 Gemelli was detained from 2 to 6 April 1694.

18 The Turks with whom he travelled from Constantinople to Trebizond, for example, turned out to be “costumed people” (Gemelli 1: 405‑6).

19 The traveller describes the Ottomans as: “utterly barbarous, uncivil, proud above all other nations, liars, much given to idleness, greedy for money, ignorant, and enemies of the Christian name. Nor is the government any better than the customs, because the trials are very short, and exposed to the falsehood of the witnesses; the cases being determined for the benefit of those who give more, not those who are more right” (Gemelli 1: 386‑7).

In the former Byzantine imperial capital on the Black Sea, Gemelli enjoyed the hospitality of the local Jesuit mission, consolidating a practice already experimented during his Mediterranean pilgrimages (Gemelli 1: 117, 408).20 For his safety, he decided to undertake the journey to Ispahan together with a small group of missionaries: Fr. Villotte, Superior of the mission of Erzurum by decree of the Sultan; Fr. Dalmatius of Auvergne, destined for the province of Şamaxı; Fr. Martin of Guyenne, directed to Ispahan; and Dominic of Bologna, a Dominican Friar directed to Aparaner (Gemelli 1: 413‑14).21 Gemelli later reported that Fr. Villotte “had well learned the Armenian language” for obvious missionary purposes, using games he invented to bring the faithful closer to Catholic doctrine (Gemelli 1: 419). This is important because it helps to explain the acquisition of so much knowledge about Armenian customs and traditions by the curious writer, who assiduously reported the names of places and settlements, rendering a pronunciation that was as close as possible to the language he heard. By doing so, he attested a fair number of Armenian toponymies along the way.

20 When he arrived in Jaffa, a few months earlier, he had to take lodging with a Jew, “neither Friars nor French being in such a small country” (Gemelli 1: 117). In Trebizond he stayed with the missionaries from 21 to 27 April 1694. The traveller was received by Fathers “dressed in Armenian fashion” (Gemelli 1: 407).

21 A fifth missionary, Fr Lau from the province of Lyons, remained in Trebizond.

Gemelli’s Trabzon was “a province between Asia Minor and Greater Armenia”, and a city in decay, of which

due to the many vicissitudes it had undergone, it must be believed that nothing has remained of its ancient splendour, as it now looks more like a village than an imperial city; indeed it looks like an inhabited forest, as there is no house that does not have its own large garden, with olive trees and other fruits, as well as the fields that are interspersed with it. (Gemelli 1: 408‑9)22

22 Gemelli also mentions a violent sacking of the city by the Russians in 1617, asserting that the same fate befell Sinope and Caffa.

The day after his landing, Gemelli was able to observe the two citadels, emphasising how both were “poorly provided with garrison and artillery” (Gemelli 1: 409‑10). In a later visit to the lower citadel, “situated on a rock, with two orders of walls and a deep moat”, he judged it to be the oldest one (Gemelli 1: 412). On 23 April, he visited the urban suburbs where, he says, “for the most part live Armenians, and Greeks, with their bishops for the exercise of their Religion” (Gemelli 1: 410). Unfortunately, the traveller does not describe Armenian churches and places of worship, showing more interest in practical aspects such as the lax customs controls. Above all, he notices that both Armenians and Greeks live in uncomfortable socio-economic conditions caused by the many taxes combined with the burden of supporting the visiting paša’s family during Ramadan (Gemelli 1: 412).

Gemelli’s small company joined a caravan to Erzurum on 27 April, finding refuge in the ruined caravanserai of Oreglan, after four hours of “mountainous and muddy” travel (Gemelli 1: 414). The journey was no less difficult in the following days, as the caravan had to cross the Zigana pass relying on small and unprotected shelters (Gemelli 1: 414‑16).23 On 30 April, the caravan reached the village of Giumis-Xane, near the silver mines which gave it its name, probability corresponding to present-day Gümüşhane, about 120 km south of Trebizond (Gemelli 1: 416‑17; cf. Barsełyan, Hakobyan, Melik‘-Baxšyan 1986, 1: 913). On 1 May the caravan passed through the village of Cuvans (Gemelli 1: 417),24 reaching after 20 miles the village of Balaxor, where it stopped at the dwelling of one of the Catergì (coachman) of the group. The Catergì was perhaps an Armenian, as Gemelli notes the hamlet was “almost all inhabited by Armenians”, and the place’s toponym seemed to be Armenian (Gemelli 1: 417‑20; cf. Barsełyan, Hakobyan, Melik‘-Baxšyan 1986, 1: 551).25 The author was struck by the architecture of the dwellings in Balaxor, described as

23 Gemelli mentions the Cuscan caravanserai (24 miles past Oreglan, possibly located in the area between the present centres of Kozağaç and Coşandere) and a second one at the foot of Mount Zigana, from which it took its name, where the caravan stopped after another 24 miles.

24 Based on the distances reported by the author, it was around the present-day village of Tekke.

25 Gemelli’s Balaxor probably corresponds to the present Akșar or its vicinity.

caves or stables […] hollowed out in the ground, that serves as a wall, with large beams placed across the top to support the roof, which is also made of earth, over which (being at the same level of the road) one can walk. In the middle they leave a very large opening to receive the light, not caring that one can then observe what is done in the house, and do more harm if one wishes […]. Beasts and men are housed in it at the same time. (Gemelli 1: 417‑18)

This is one of the rare descriptions of the traditional architecture of the glxatun type, of ancient memory, which the traveller found in other villages along the route to the Persian border, such as Avirac and Carvor (Gemelli 1: 422‑3; cf. Donabédian 2008, 50 fn. 121, fig. 92) [fig. 3]. Although Gemelli considered the accommodation inelegant and referred to it henceforth as a “stable”, he also stated its functionality.

Figure 3 Relief and plan of a glxatun type dwelling, from © Donabédian 2008, 50, fig. 92

The caravan drove 12 miles later to the city of Beiburt (Bayburt), which Gemelli reports as a centre of manufacturing and trade of “good woollen carpets” (Gemelli 1: 414), perched on a rock, surrounded by walls, but with weaponry lacking. After another six miles along the Č‘orox river, the caravans were camped at a place called Maaciur (perhaps the Armenian village of Mahaǰur) (Gemelli 1: 421; cf. Barsełyan, Hakobyan, Melik‘-Baxšyan 1986, 1: 652).26 After stopping “in the house, or, to put it better, the stable of an Armenian” (Barsełyan, Hakobyan, Melik‘-Baxšyan 1986, 1: 364), near Avirak, and then in another “stable” in Carvor,27 the caravan ended up, on 6 May, in the village of Teurischiuch (Tebrizcik, arm. T‘aruǰuk), arriving the next morning in the city of Erzurum (Gemelli 1: 422‑4; cf. Barsełyan, Hakobyan, Melik‘-Baxšyan 1988, 2: 422).

26 An approximate calculation of distances suggests a location near the modern Medan.

27 It is conceivable that Carvor was located near the present Kügükegeçit, 5 km east of Ashkale, and a village called Avirak is reported in the same province.

Gemelli describes its plateau as fertile, well cultivated and populated by various hamlets, almost scenically “crowned with snow-covered mountains”. He reports that Erzurum resembled Constantinople for its walls “defended by a middle ditch and by several towers placed at a suitable distance and equipped with small pieces of artillery called falconets”. Next to the Janissaries’ Castle, Gemelli remarked the presence of “the Archiepiscopal Church of the Armenians, much of it ruined, except for two towers that are made of brick” and low houses made of wood and mud “mostly inhabited by Armenians”, flanking narrow streets without cobblestones which lead to ordinary bazaars, as well as 22 caravanserais. According to Gemelli, as well as many authors, one of the most remarkable features of Erzurum was its cold climate, as well as its proximity to the Euphrates. The stay in Erzurum ended abruptly after ten days because of the Armenian Apostolic Church’s aversion to Catholic missionaries. The local authorities, who pandered to the Church, acted so hostile that Gemelli and his companions fled the city at night, in secret (Gemelli 1: 424‑38).28

28 Two years earlier, the Jesuits were forced to leave the city, and the same happened in Trebizond. The phenomenon can be interpreted in terms of harmony between the local Ottoman government and the Armenian ecclesiastical hierarchy.

The group stayed overnight in the village of Axa, four miles from the fortified centre of Hassan-kale (near the present day Pasinler, Gemelli 1: 439).29 On 19 May they passed the Taliscì customs post, the bridge of Scio.ban.nuprì (sic) (probably Yeniçobandede), reaching after 28 miles Korason, a village on the left bank of the Arax, with houses “like those of Balaxor”, and where women “cover their faces, almost Egyptian-style, with certain small silver plates, [as large] as a Neapolitan carlin, which with the movement of their heads also make a graceful sound; and on each side of the robe there are two orders of large buttons, with other small silver plates”. This was probably the Armenian village of Korasan (modern Akkiran) and the women’s clothes described were Armenian as well (Gemelli 1: 428, 440‑1).30

29 Cf. Barsełyan, Hakobyan, Melik‘-Baxšyan 1991, 3: 368‑9; Chiesa 2011, 506‑7.

30 Cf. Barsełyan, Hakobyan, Melik‘-Baxšyan 1988, 2: 794; Nisanyan Envanteri. Gemelli was careful in reporting women’s clothing, which was also the case in Erzurum, where women dressed in “boots, and a black cloth in front of the forehead, to hide their faces” (Gemelli 1: 428), and a knee-length cloth on their heads.

From this point on, Gemelli’s narrative becomes more confused, probably reflecting the roughness of a mountainous route and the threat of bandits. The caravan reached a place named Misinghirt; contrary to his custom, Gemelli does not specify the distance from the previous halting place, which, however, must have been at least 15 km.31 From this fortified centre populated by “many Christians” and some Kurdish settlements, the group reached a rural hamlet inhabited by Armenians called Cotanlò, 12 miles from Kars (Gemelli 1: 442‑3).32

31 This place could be identified with the Armenian Mžnkert already mentioned in the thirteenth century by William of Rubruk and probably located in the vicinity of today’s Bulgurlu. Cf. Guglielmo di Rubruk 2011, 310; Barsełyan, Hakobyan, Melik‘-Baxšyan 1991, 3: 814‑15; Harut‘yunyan 2007, 87; Boschis 2023, 148 fn. 32.

32 This could be the Armenian village of Kotanlu, cf. Barsełyan, Hakobyan, Melik‘-Baxšyan 1991, 3: 225.

The company arrived in the border city of Kars, the last before entering Safavid territory, on Sunday 23 May and left after two days. Despite the short time, Gemelli managed to sketch out a minimal description of civil and military structures rather than the religious ones [fig. 4].33 Kars was a large but sparsely populated city, which, being on the frontier between enemy empires, was too often victim of ravages from both Turkish and Persian armies. The destruction wrecked on the region by wars was visible for “eight, nine, days of march” (Gemelli 1: 445‑8). The only exception to this desolation seemed to him to be the Bagratid capital, Anì-kagaë (Ani), with its still-standing walls and monastic ruins (Gemelli 1: 448‑9) [fig. 5].34 After passing through the Ottoman fort of Arpaçay and crossing the Axuryan river, the caravan entered the Safavid territory, to the relief of Gemelli, who, as soon as he reached the opposite bank, dismounted from his horse and kissed the long-awaited land, now out of the reach of any “Turkish slyness” (Gemelli 1: 449‑50).

33 Gemelli mentions neither the church of St. Aṙak‘loc‘ (tenth century), nor the nearby Beşik kilise, both of which are clearly visible, centrally located in the lower township, on the opposite bank of the river from the upper citadel. Cf. Cuneo 1988, 686‑7, 689; Ferrari 2019, 124‑43.

34 Cf. Ferrari 2019, 90‑123. The caravan reached Ani after stopping in the unidentified village of Chialà, 30 miles away from Kars.

Figure 4 Kars, church of St. Aṙak‘eloc‘, tenth-thirteenth centuries. Photograph by Łukasyan, 1941. Courtesy of the © History Museum of Armenia, inv. no. 468

Figure 5 Ani, northern wall, tenth century. Courtesy of © History Museum of Armenia, inv. no. 270

By the evening of the same day, 26 May 1694, the company stopped in Talen, “the first village of Persians”. Gemelli wrote:

There was already an excellent church here, for the use of the Armenian Christians, who make up the majority of the inhabitants; the figures of the Holy Apostles can be seen painted on the high altar; however, it has now fallen into disrepair, like another adjacent one. (Gemelli 2: 2‑3)

This is the first known description of the monumental complex of T‘alin, its cathedral and its St. Astvacacin church (seventh century) [figs 6‑8].35 Gemelli was attracted by the fading apsidal paintings, among which he recognised the figures of the Apostles in the second register, today barely visible [fig. 9].

35 Donabédian 2008, 118‑22, 146‑7.

The next day the company reached Ēǰmiacin, where Fr. Villotte acted as Gemelli’s guide, instructing him on the history of the Armenian Church and on legendary and etymological anecdotes.36 An important description of the cathedral is provided by Gemelli: domed, cruciform, accessible through three entrances and floors covered with carpets, three altars and a patriarchal seat, as well as a series of service buildings including a convent, the patriarchal residence, gardens with fountains and the guesthouse where Gemelli himself with his companions passed the night (Gemelli 2: 4‑5).37

36 This good-natured missionary is the same Jacobus Villotte (1656‑1743), the author of a Latin-Armenian dictionary printed under the patronage of Propaganda Fide in 1714, as well as of a mission report to the East published in Paris in 1730, cf. Villotte 1714; Villotte, Frizon 1730; Tadevosyan 2001‑02.

37 Gemelli also briefly described the martyria of St. Gayanē and St. Hṙip‘simē, but did not mention St. Šołakat‘, the construction of which began in 1694, cf. Cuneo 1988, 88‑101; Donabédian 2008, 83‑7, 105‑7.

The next morning, after the office celebrated in the cathedral by 70 monks (Gemelli 2: 6‑8), the group reached Erivan, where Gemelli lodged at the only caravanserai in the city, rather than in the city’s Jesuit residence. The description he supplies of the administrative centre of Safavid Armenia is critical of defence devices and building techniques, but he is fascinated by the organisation of activities, from the bazaars to the palace of the Sardar (governor), from the method of making coins at the Mint to the origin of the main source of water, the Hrazdan river and its beautiful bridge. Walking through hamlets and gardens Gemelli did not record any information about the religious architecture, then represented at least by the churches of St. Astvacacin, St. Połos-Petros and the chapel of Gethsemane.38 What he dwells on instead is the damage caused to the city by the Ottoman wars, neglecting to mention the disastrous earthquake of June 1679, whose effects were probably still evident at the time (Gemelli 2: 8‑10).39

38 St. Astvacacin is the only medieval church in Erevan, while the other two mentioned were destroyed in the 1930s in the implementation of the new urban plan approved by the Soviet authorities in 1924. The church, also called kat‘ołike, was among the few city structures to withstand the 1679 earthquake, following which St. Ananias Zoravar (1694) had to be rebuilt. The old churches of Avan, St. Astvacacin and St. Hovhannēs were at the time quite isolated from the city centre. Cf. Cuneo 1988, 110‑13; Shahaziz 2003.

39 Regrettably, unlike Chardin (in 1672), Gemini published few engravings of his trip to the Near East, none of which concern Armenia; it would have been extremely useful to compare engravings from just before and just after the 1679 earthquake.

On 1 June, Gemelli made an excursion to the monastery of Gełard, “cut into the rock, of which are also made the pillars that support the church”, an aspect as impressive in his eyes as the presence of the Holy Lance relic in the treasury. The author also mentions the presence of five other monastic centres in the surroundings.40 On his return to Erevan, Gemelli dined at the Jesuit residence, but provides no information about its location.

40 Cf. Cuneo 1988, 136‑9; Sahinian, Monoukian, Aslanian 1972.

On Saturday 5 June he left for Naxiǰevan with Fr. Dominic, joining a Georgian caravan (Gemelli 2: 11‑17). Heavy rain forced the group to make frequent stops, first in Gavuri-ciny, then in Satarach (Sədərək, AZ; Barsełyan, Hakobyan, Melik‘-Baxšyan 1998, 4: 459). Passed the guard post on the Arp‘a River, the caravan reached the caravanserai of Karaba (nowadays Qarabaqlar, AZ; Barsełyan, Hakobyan, Melik‘-Baxšyan 1988, 2: 937), whose square factory was, according to Gemelli, one “of the most spacious and beautiful I have ever seen” (Gemelli 2: 17). Nearby there was a spring by Armenian legends said to have been created by Sem, Noah’s son.

On 8 June 1694, the group arrived in Naxiǰevan (Gemelli 2: 17‑20), where Fr. Dominic directly left for the monastery of Aparaner, leaving Gemelli as the sole target of robbery by the city guards. The situation became so dire to remind him the misadventures suffered in Erzurum, and he considered Nak Civan to be its Persian equivalent. Gemelli dedicates to it a succinct description, recalling the legend of its foundation by Noah,41 and remarking how its buildings, “reduced to nothing by constant wars” (Gemelli 2: 18), were relics of the glorious past. The modern village was small, with only one narrow street, a good bazaar and four large caravanserais. Its houses were made like caves. What impressed Gemelli the most was the exotic building visible just outside the city, made of bricks “more than 70 palms high, octagonal in shape, ending spire-like”, with “two tall towers on either side, without any communication with the spire” (Gemelli 2: 19), which he assumes to be of Timurid age, but truly the mausoleum of Momine Xat‘un (1186). Gemelli does not mention Armenian churches. Most of them were razed to the ground in the thirteenth century, so that of the original eighty churches only two remained, probably St. Errordut‘yun (seventh-eighth century, destroyed in 1975) and St. Gevorg (rebuilt on older structures in 1869, now disappeared).42 Because of the guards’ abuses, Gemelli decided to leave the same night, taking advantage of the company of a Persian envoy on his way to Ispahan (Gemelli 2: 20‑1).

41 Abaraner (or Aparaner) corresponds to today’s Bənəniyar in Azerbaijani territory.

42 Cf. Guglielmo di Rubruk 2011, 302‑6; Ayvazyan 1986; Cuneo 1988, 466; Barsełyan, Hakobyan, Melik‘-Baxšyan 1991, 951‑5; Karapetyan 2012, 25.

The next morning, on a poorly crafted and very badly steered boat, he crossed the Araxes in the vicinity of the ancient J̌ułay, according to him an uninhabited “heap of mud and caves built underground” with “two caravanserais, built at great expense by the Armenian Coggia [arm. xoǰa] Nazar on either side of the river, [...] also ruined”. The description depicts the desolation into which the city, once a small but flourishing centre on the so-called Silk Road before the Persian deportation, had fallen at the time. Gemelli’s annotations on his contemporary J̌ułay, disdainful of its buildings, are the result of an increasingly confident European mentality of superiority, from which even the jurist could not escape. The passage reveals a certain hastiness in writing: Gemelli does not mention the presence of churches, chapels and cemeteries reported by other travellers, probably because he did not even have the time to notice them while fleeing early in the morning.43 Quite a pity, because it would have been interesting to know whether the underground caverns he mentioned were of the same type as those he had already encountered in the provinces of Ottoman Armenia, and whether they were only inside or also outside the walls, made of raw brick rather than mud. What is certain is that with the crossing of Arax, the Italian traveller’s experience in the lands of Historical Armenia came to an end.

43 Gemelli does not mention any of the at least five ancient churches that should have been in the city at the time: St. Amenap‘rkič‘ Pomblozi (Hovvi), St. Astvacacin, St. Hovhannes e St. Gevorg, cf. Cuneo 1988, 476; Barsełyan, Hakobyan, Melik‘-Baxšyan 1998, 426‑8; Karapetyan 2012, 25.

Figure 6 T‘alin, cathedral (seen from the west), late seventh century. Photo by the Author, June 2022 (before restoration currently underway)

Figure 7 T‘alin, church of St. Astvacacin, late seventh century. Photo by T‘. T‘oramanyan, beginning of the twentieth century. Courtesy of © History Museum of Armenia, inv. no. 640

Figure 8 T‘alin, church of St. Astvacacin, after the latest restoration. Photo by the Author, June 2022

Figure 9 T‘alin, cathedral, wall paintings in the apse, late seventh century. Photo by the Author, June 2022

3 Conclusions

Despite his having received little attention in historical studies, Gemelli’s Giro del mondo constitutes a valuable source of knowledge of Armenian history and culture in many respects. The author, well disposed towards the Armenians, who according to him were schismatics but still devoted and good-hearted Christians, often sought refuge and support in case of need or simply out of preference among the Armenians, both in the Ottoman and Persian Empires, from Smyrna to Ispahan (Gemelli 1: 21, 2: 35). Considered to be the first tourist in history and, by his own admission, a traveller “moved by natural wanderlust” (Gemelli 1: 2), he was an attentive observer, rigorous in distinguishing data from unverifiable hearsay, sometimes quick to judge cultural attitudes different from his own, yet demonstrating great intelligence in going beyond the preconceptions consolidated in his mind by education and experience (Gemelli 1: 413, 429‑3, 2: 3).44

44 This is true in both positive and negative terms, for despite Gemelli’s esteem for the Armenian people, he is also sharply critical of the Armenian clergy. In some cases, Gemelli’s negative attitude was influenced by the Armenian clergy’s blatant rivalry with Catholic missionaries, as in Erzurum, in other occurrences it was linked with simpler, everyday contexts, such as his encounter with the superstitious Vardabietto (Vardapet) of T‘alin.

This reconstruction of Gemelli’s journey through the provinces of Historical Armenia highlights the relevance of his account for investigating the spread of Armenian communities in lands that today belong to Turkey and Azerbaijan, as well as studying Armenian toponymy. From an art historical perspective, Gemelli’s contribution cannot be considered more precise or detailed than other works, but it remains important. Neither the references to the popular architecture of the hypogeal Armenian houses, nor the description of the jewellery and traditional clothing are trivial. Through the pages of the Giro, one seems to be able to relive the ancient atmosphere breathed in villages now lost, such as Balaxor, Avirak, Carvor and Korason.

The same can be said for urban realities such as Trebizond, Erzurum, Kars and Erevan, although the descriptions of places and monuments are not as exhaustive as a modern scholar might wish, focusing mainly on aspects of the military, economic and administrative organisation rather than on the appearance of churches and monasteries, usually briefly mentioned in relation to the presence of religious communities. An important and physiological exception is the Patriarchal See of Ēǰmiacin, which greatly fascinated Gemelli: much remains to be said about the evolution of its churches, particularly the cathedral, which was much altered over the centuries.

Reports on caravanserais and ancient bridges (especially in the Naxiǰevan area, sadly notorious for the physical and cultural obliteration of Armenia’s artistic heritage) would also need to be discussed separately. In this sense, Gemelli’s thin descriptions, which are the results of short stints more than thoughtful sojourns, are very useful and interesting, as seen in the case of J̌ułay and its muddy houses. Certainly, it would have been useful to know more about the Armenian churches in ruins in the Ottoman domains, as well as about the appearance, name, and location of the “many hermitages inhabited by Christian Religious” (Gemelli 2: 14) scattered at the foot of Ararat. Gemelli, on the other hand, without omitting linguistic information such as the mountain’s Armenian and Persian names (Masesusar and Agrì respectively), takes care to point out how its summit was always visible in the morning and always obstructed from view by a crown of dense clouds “from vespers onwards” (Gemelli 2: 14). To appreciate fully the importance of the testimony of this eclectic wayfarer-writer, it must be contextualised within the cultural framework of which it was a brilliant product.

Bibliography

Primary sources

Amat di S. Filippo, P. (1882). Biografia dei viaggiatori italiani colla bibliografia delle loro opere. Roma: Società geografica italiana.

Chardin, J. (1711). Voyages de Monsieur le Chevalier Chardin, en Perse et autres lieux de l’Orient. 3 vols. Amsterdam: Jean Louis de Lorme.

Chiesa, P. (a cura di) (2011). Guglielmo di Rubruk: Viaggio in Mongolia (Itinerarium). Milano: Fondazione Valla.

Du Halde, J.-B. (1722). “Aux Jésuites de France”. Le Gobien, C.; Du Halde, J.-B.; Patouillet, L. (éds), Lettres édifiantes et curieuses, écrites des missions étrangères, vol. 15. Paris: Le Clerc.

Gemelli Careri, G.F. (1699‑1700). Giro del Mondo. 6 vols. Napoli: Rosselli.

Guglielmo di Rubruk (2011). Viaggio in Mongolia (Itinerarium). A cura di P. Chiesa. Milano: Fondazione Lorenzo Valla; Arnoldo Mondadori Editore.

Invernizzi, A. (a cura di) (2001). Pietro della Valle: In viaggio per l’Oriente. Le mummie, Babilonia, Persepoli. Alessandria: Edizioni dell’Orso.

Ker Porter, R. (1821). Travels in Georgia, Persia, Armenia, Ancient Babylonia &c. &c., During the Years 1817, 1818, 1819, and 1820. 2 vols. London: Longman-Hurst-Rees-Orme-Brown.

Layard, H.A. (1853). Discoveries Among the Ruins of Niniveh and Babylon; with Travels in Armenia, Kurdistan, and the Desert. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers.

Lynch, H.F.B. (1901). Armenia: Travels and Studies. 2 vols. London: Longmans Green & Co.

Villotte, J. (1714). Dictionarium novum latino-armenium. Roma: Typis Sacrae Congregationis de Propaganda Fide.

Villotte, J.; Frizon, N. (1730). Voyages d’un missionaire de la Compagnie de Jesus, en Turquie, en Perse, en Arménie, en Arabie, & en Barbarie. Paris: Jacques Vincent.

Secondary sources

Adey, P. et al. (eds) (2014). The Routledge Handbook of Mobilities. London: Routledge.

Ayvazyan, A. (1986). Naxiǰevani ISSH haykakan hušarjannerə (Armenian Monuments in the Autonomous Republic of Naxiǰevan). Erevan: Hayastan.

Ballo Alagna, S. (1997). “Italiani intorno al mondo. Suggestioni, esperienze, immagini dai diari di viaggio di Antonio Pigafetta, Francesco Carletti, Gian Francesco Gemelli Careri”. AGEI-Geotema, 8, 107‑25.

Barsełyan, H.X.; Hakobyan, T‘.X.; Melik‘-Baxšyan; S.T. (eds) (1986). s.v. “Avirak”. Hayastani ev harakic‘ šrǰanneri tełanunneri baṙaran (Dictionary of Toponyms of Armenia and Bordering Regions), vol. 1. Erevan: Hamalsarani hr., 364.

Barsełyan, H.X.; Hakobyan, T‘.X.; Melik‘-Baxšyan, S.T. (eds) (1986). s.v. “Balaxor”. Hayastani ev harakic‘ šrǰanneri tełanunneri baṙaran (Dictionary of Toponyms of Armenia and Bordering Regions), vol. 1. Erevan: Hamalsarani hr., 551.

Barsełyan, H.X.; Hakobyan, T‘.X.; Melik‘-Baxšyan, S.T. (eds) (1986). s.v. “Gyumišxane”. Hayastani ev harakic‘ šrǰanneri tełanunneri baṙaran (Dictionary of Toponyms of Armenia and Bordering Regions), vol. 1. Erevan: Hamalsarani hr., 913.

Barsełyan, H.X.; Hakobyan, T‘.X.; Melik‘-Baxšyan, S.T. (eds) (1986). s.v. “Mahaǰur”. Hayastani ev harakic‘ šrǰanneri tełanunneri baṙaran (Dictionary of Toponyms of Armenia and Bordering Regions), vol. 1. Erevan: Hamalsarani hr., 652.

Barsełyan, H.X.; Hakobyan, T‘.X.; Melik‘-Baxšyan, S.T. (eds) (1988). s.v. “Karaba”. Hayastani ev harakic‘ šrǰanneri tełanunneri baṙaran (Dictionary of Toponyms of Armenia and Bordering Regions), vol. 2. Erevan: Hamalsarani hr., 973.

Barsełyan, H.X.; Hakobyan, T‘.X.; Melik‘-Baxšyan, S.T. (eds) (1988). s.v. “T‘aruǰuk”. Hayastani ev harakic‘ šrǰanneri tełanunneri baṙaran (Dictionary of Toponyms of Armenia and Bordering Regions), vol. 2. Erevan: Hamalsarani hr., 422.

Barsełyan, H.X.; Hakobyan, T‘.X.; Melik‘-Baxšyan, S.T. (eds) (1991). s.v. “Hassankala”. Hayastani ev harakic‘ šrǰanneri tełanunneri baṙaran (Dictionary of Toponyms of Armenia and Bordering Regions), vol. 3. Erevan: Hamalsarani hr., 368‑9.

Barsełyan, H.X.; Hakobyan, T‘.X.; Melik‘-Baxšyan, S.T. (eds) (1991). s.v. “Kotanlu”. Hayastani ev harakic‘ šrǰanneri tełanunneri baṙaran (Dictionary of Toponyms of Armenia and Bordering Regions), vol. 3. Erevan: Hamalsarani hr., 225.

Barsełyan, H.X.; Hakobyan, T‘.X.; Melik‘-Baxšyan, S.T. (eds) (1991). s.v. “Mžnkert”. Hayastani ev harakic‘ šrǰanneri tełanunneri baṙaran (Dictionary of Toponyms of Armenia and Bordering Regions), vol. 3. Erevan: Hamalsarani hr., 814‑15.

Barsełyan, H.X.; Hakobyan, T‘.X.; Melik‘-Baxšyan, S.T. (eds) (1998). s.v. “Sadarak”. Hayastani ev harakic‘ šrǰanneri tełanunneri baṙaran (Dictionary of Toponyms of Armenia and Bordering Regions), vol. 4. Erevan: Hamalsarani hr., 459.

Barthold, V.V. (1947). La découverte de l’Asie. Histoire de l’Orientalisme en Europe et en Russie. Paris: Payot.

Berchet, J.-C. (1985). Le voyage en Orient. Anthologie des voyageurs français dans le Levant au XIXe siècle. Paris: Laffont.

Biasiori, L.; Mazzini, F.; Rabbiosi, C. (2023). Reimagining Mobilities Across the Humanities, Abingdon: Routledge.

Boschis, A. (2023). “‘Omnia depinxissem vobis si scivissem pingere!’. L’Armenia nell’Itinerarium di fra Guglielmo di Rubruk”. Eurasiatica, 20, 133‑66.

Buccini, S. (1996). “Coerenza metodologica nel Giro del mondo di Giovanni Francesco Gemelli Careri”. Annali d’Italianistica, 14, 246‑56.

Ciampi, I. (1859). Il Gemelli. Discorso. Vol. 5, Saggi e riviste. Roma: Aureli.

Croce, B. (1929). Storia dell’età Barocca in Italia. Bari: Laterza.

Cuneo, P. (1988). Architettura armena: dal quarto al diciannovesimo secolo, vol. 1. Roma: De Luca.

De Gubernatis, A. (1875). Storia dei viaggiatori italiani nelle Indie orientali. Livorno: Vigo.

de Vargas, P. (1955). “Le Giro del mondo de Gemelli Careri, en particulier de récit du séjour en Chine. Roman ou vérité?”. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Geschichte, 5, 417‑51.

Demus, O. (2008). L’arte bizantina e l’Occidente. Torino: Einaudi. Trad. it. di: Byzantine Art and the West, New York: New York University Press, 1970. The Wrightsman Lectures 3.

Donabédian, P. (2008). L’âge d’or de l’architecture arménienne. VIIe siècle. Marseille: Parenthèses.

Dorfmann-Lazarev, I.; Khatchadourian, H. (2023). Monuments and Identities in the Caucasus: Karabagh, Nakhichevan and Azerbaijan in Contemporary Geopolitical Conflict. Leiden; Boston: Brill.

Doria, P. (2000). s.v. “Giovanni Francesco Gemelli Careri”. Dizionario biografico degli italiani, vol. 53, Roma: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 42‑5.

Fatica, M. (1998). “L’itinerario sinico di Giovanni Francesco Gemelli Careri. Saggio di decrittazione degli antroponimi europei e dei toponimi cinesi nel Giro del mondo”. Faizah, S.; Rivai, S.; Santa Maria, L. (a cura di), Persembahan. Studi in onore di Luigi Santa Maria. Napoli: Istituto Universitario Orientale, 45‑67.

Ferrari, A. (2019). L’Armenia perduta. Viaggio nella memoria di un popolo. Roma: Salerno.

Galeota, V. (1994). “Il Viceregno della Nuova Spagna nel Giro del mondo di Gemelli Careri”. Crovetto, P.L. (a cura di), Andando más, más se sabe. Atti del Convegno internazionale “La scoperta dell’America e la cultura italiana” = Conference Proceedings (Genova, 6‑8 Aprile 1992). Roma: Bulzoni, 287‑95.

Ghirlanda, G. (1899). Gianfrancesco Gemelli Careri e il suo viaggio intorno al mondo (1693‑1698). Verona: Paderno.

Grigoryan, A. (ed.) (2015). Ani. The Millennial Capital of Armenia. Erevan: Tigran Mec.

Grossi, G.B.G. (1820). s.v. “Francesco Gemelli Careri”. Biografia degli Uomini Illustri del Regno di Napoli, vol. 7. Napoli: Stamperia di Nicola Gervasi.

Guglielminetti, M. (1967). Viaggiatori del Seicento. Torino: UTET.

Harut‘yunyan, B.H. (2007). Hayastani patmut‘yan atlas, vol. 1. Erevan: Macmillan Armenia.

Hester, N. (2008). Literature and Identity in Italian Baroque Travel Writing. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Holmberg, J.E. (2024). Writing Mobile Lives, 1500‑1700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Invernizzi, A. (a cura di) (2001). Pietro della Valle. In viaggio per l’Oriente. Le mummie, Babilonia, Persepoli. Alessandria: Edizioni dell’Orso.

Invernizzi, A. (2005). Il genio vagante. Viaggiatori alla scoperta dell’antico Oriente (secc. XII-XVIII). Alessandria: Edizioni dell’Orso.

Invernizzi, A. (2012). Il viaggio in Asia (1671‑1675) nei manoscritti di Minneapolis e di Bergamo. Alessandria: Edizioni dell’Orso.

Karagezjan, G. (2019). Naxičevan v zapiskax evropejskix putešestvennikov (XIII-XVII vv.) (Naxiǰevan in the Notes of European Travellers, thirteenth-seventeenth Centuries). Erevan: Izd.-vo “Gitutjun” NAN.

Karapetian, S. (ed.) (2012). Nakhijevan Atlas. Yerevan: Research on Armenian Architecture, Tigran Metz Publishing House.

Kéfélian, A. (2021). “Regards croisés de voyageurs occidentaux sur le site de Gaṙni”. Ferrari, A.; Haroutyunian, S.; Lucca, P. (a cura di), Il viaggio in Armenia. Dall’antichità ai nostri giorni. Venezia: Edizioni Ca’ Foscari, 62‑89. Eurasiatica 17.

http://doi.org/10.30687/978‑88‑6969‑497‑4/004

Maccarone-Amuso, A. (2000). Gianfrancesco Gemelli-Careri: L’Ulisse del XVII secolo. Roma: Gangemi.

Magnaghi, A. (1900). Il viaggiatore Gemelli Careri (secolo XVII) e il suo “Giro del mondo”. Bergamo: Cattaneo.

Magnaghi, A. (1932). s.v. “Gemelli Careri, Giovanni Francesco”. Enciclopedia Italiana, vol. 16. Roma: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 493‑4.

Menestò, E. (1993). “Relazioni di viaggi e di ambasciatori”. Cavallo, G.; Leonardi, C.; Menestò, E. (a cura di), Lo spazio letterario del Medioevo. Vol. 1, Il Medioevo latino. La produzione del testo. Roma: Salerno, 535‑600.

Merriman, P.; Pearce, L. (2017). “Mobility and the Humanities”. Mobilities, 12(4), 493‑508.

Negro Spina, A. (2001). Un viaggiatore del Seicento in giro per il mondo: Giovan Francesco Gemelli Careri. Napoli: Bowinkel.

Nelles, P.; Salzberg, R. (2023). Connected Mobilities in the Early Modern World. The Practice and Experience of Movement. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Nisanyan Envanteri (Inventario Nisanyan) = Nisanyan Yeradları Türkiye ve Çevre Ülkerer Yerleşim Birimleri Envanteri (Nisanyan Inventory of Toponyms of Settlements in Turkey and Neighbouring Countries).

Nunnari, F. (1901). Un viaggiatore Calabrese della fine del secolo XVII. Messina: Mazzini.

Pedrini, G. (2011). Sguardi veneziani a Oriente. Ambrosio Bembo e il suo viaggio per parte dell’Asia [PhD dissertation]. Venezia: Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia.

Perocco, D. (1985). “Fenomenologia dell’esotismo: viaggiatori italiani in Oriente”. Braudel, F. (a cura di). Storie di viaggiatori italiani. Vol. 1, L’Oriente. Milano: Electa, 144‑65.

Prevost, A.-F (1753). Histoire générale des voyages, vol. 2. Paris: Didot.

Reichert, F.E. (1992). Incontri con la Cina. La scoperta dell’Asia Orientale nel Medioevo. Milano: Biblioteca francescana. Trad. it. di: Begegnungen mit Cina. Die Entdeckung Ostasiens im Mittelalter. Stuttgart: Jan Thorbecke Verlag, 1992.

Sahinian, A.; Monoukian, T.A.; Aslanian, A. (eds) (1972). G(h)eghard. Vol. 6, Documents of Armenian Architecture = DAA. Milano: Ares.

Sarzi Amade, J. (2012). “Gianfrancesco Gemelli-Careri: ‘Vagabundu, spiuni, jettaturi’”. Quaderni d’italianistica, 33(1), 121‑43.

Searight, S. (1979). The British in the Middle East. London: The Hague.

Shahaziz, Y. (2003). Old Yerevan. Erevan: Mułni hr.

Surdich, F. (2017). Viaggiatori, pellegrini, mercanti sulla Via della seta. Milano: Luni.

Tadevosyan, Y. (2001‑02). “The Armenian Terminology: Jacob Villot’s Latin-Armenian Dictionary”. Slovo, 64‑72, 111‑16.

Urry, J. (2007). Mobilities. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Vece, V. (1906). Il viaggiatore Calabrese Gemelli-Careri e il suo giro intorno al mondo. Napoli: Maddaloni.

Zeri, A. (1904). “Il primo giro del mondo compiuto da un viaggiatore italiano: Gianfrancesco Gemelli Careri”. Rivista marittima, 37(4), 253‑79.

Zoli, S. (1972). “Le polemiche sulla Cina nella cultura storica, filosofica, letteraria italiana della prima metà del Settecento”. Archivio Storico Italiano, 130, 3/4(475), 409‑67.