From Distant to Public Reading

The (Hebrew) Novel in the Eyes of Many

Abstract From its very beginning, the term “distant reading” (Moretti 2000) was controversial, displacing ‘close reading’ by relying on literary histories and thereby reflecting on the entire global literary system. One of the weaknesses of this approach lies in its exclusive reliance on canonical and authoritative historiographies, one or two for each national literature, something which is bound to over-simplify the complexities of national literatures. As is known, Moretti’s proposal became a ‘slogan’ for Digital Humanities while algorithmic manipulation of texts has taken the place of reading literary (human) histories. Yet the problem of over-simplification remains, albeit differently. As an alternative, we offer a fusion approach, radicalising Moretti’s idea. In this article, we demonstrate how computer-based analysis of different readings carried out by many readers – not necessarily professionals – produces a relatively minute picture. Our case study will be the Hebrew novel, from its emergence in 1853 to the present day; a manageable corpus on which we gather information using questionnaires we have carefully created in our lab. Alongside the presentation of our approach, the actual research, and its initial findings, we will reflect theoretically on the conceptual benefits, as well as the limits, of public distance reading.

Keywords Distant reading. Computational literary studies. The novel. Hebrew literature. Public reading.

title

1 Introduction: Size

“Some people have read more”, wrote Franco Moretti in one of the most quoted paragraphs in what later became a kind of manifesto of the Digital Humanities,

but the point is that there are thirty thousand nineteenth-century British novels out there, forty, fifty, sixty thousand – no one really knows, no one has read them, no one ever will. And then there are French novels, Chinese, Argentinian, American... Reading ‘more’ is always a good thing, but not the solution. (2000a, 55)

Clearly, at this early stage, Moretti had not thought of computers; he merely wanted to point out the limitations of close reading. And he chose to do so in a way that echoes Erich Auerbach’s remarks on the exact same issue, in the last article he published before his death nearly fifty years earlier ([1952] 1969). But in an age of growing data, it is no wonder that this paragraph caught the eyes of scholars who suggested various alternatives to good old human reading. From “Distant Reading” (Moretti 2000a) to “Macroanalysis” (Jockers 2013), from “Surface Reading” (Best, Marcus 2009) to “Algorithmic Criticism” (Ramsay 2011), from “Cultromics” (Michel et al. 2011) to “Cultural Analytics” (Manovich 2020), and beyond, the size – the size of what is known as “the great unread” (Cohen 1999, 23) – is presented as a problem. And while size, in and of itself, is not the only problem that the Digital Humanities are having to deal with, it is probably one of the most prominent ones. In effect, focusing on size widens the gap between Digital Humanities and the more traditional humanities. Because, for all the desire for reading that does move between closeness and distance – a position that many uphold (Hammond 2017) – in the end, as graphically described by Jean-Baptiste Michel et al.,

[i]f you tried to read only English-language entries from the year 2000 alone, at the reasonable pace of 200 words/min, without interruptions for food or sleep, it would take 80 years. The sequence of letters is 1000 times longer than the human genome: if you wrote it out in a straight line, it would reach to the Moon and back 10 times over. (2011, 176)

The scale chosen here to describe the size of the corpus is not accidental: it is difficult to think of a more challenging task, for a machine-less person, than that of occupying outer space.1

1 Michel et al. deal with books in general, not necessarily with belles lettres, but they call into question, and in a very figurative way, the notion of size. Moretti himself, dealing with prose, described it in a way more familiar to the experience of a human reader: “a novel a day every day of the year would take a century or so” (2005, 4). Complexity, in addition to size, is another problem raised by textual data; and there is a close connection between these two, as shown by Schöch (2013).

But what if we were able to read the ‘great unread’? In our field, of modern Hebrew literature, Moretti’s description above, as well as the metaphorical journey to outer space, are simply not relevant. Although no one knows exactly how many Hebrew novels have been written – and we will return to this point later – we can calculate roughly how many have been published since the first one, Ahavat Zion (The Love of Zion), was published by Avraham Mapu in 1853.2 And the number is not that big: the community of readers of modern Hebrew literature was quite small in the first decades of the genre’s existence. A new Hebrew language, allowing for essential daily communication that did not rely solely on the language of the sacred sources, had only just begun to emerge. Thus, from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century, a few dozen novels, at most, were published, while the prestige of Hebrew literature was bestowed on two other of its forms: poetry and short stories. From the middle of the twentieth century onwards, the trend began to change. And although poetry and short stories continued to be written, the novel gained a significant place (both quantitatively and qualitatively), a process that reflected diverse cultural, national and political developments. From the establishment of the State of Israel (1948) until the time that these lines are being written, a few thousand novels have been published. So, all in all, the total number of Hebrew novels apparently does not exceed 8,500. While not an insignificant number, it is not an unwieldy one.

2 A few of the significant historiographies of Modern Hebrew Literature include the ones written by Gershon Shaked ([1977] 2000); Dan Miron (1979; 2010) and Yigal Schwartz (2005). Works on the Hebrew novel – as an independent genre – are not many, including inter alia Holtzman’s (1990) and Netanel’s (2016).

At this point in time, fortunately, it does not require getting to the moon and back. Many scholars, especially the oldest ones, have read a lot of the material. And from a computational perspective, as described by Marienberg-Milikowsky, it is a fairly convenient corpus: large enough for algorithmic reading, but not too large for human reflection (Marienberg-Milikowsky 2019). The question is, however, can we reverse the picture? Is it humanly feasible for us to re-read the great read, with mechanised reflection? How can we handle such a large-yet-manageable corpus? What are some of the methodological approaches we might use to reach beyond the canon? Alone, of course, we are not able to do that. But “some people have read more”... maybe they can help? Maybe ‘reading more’ is a solution?

In the subsequent sections of this contribution we turn to examine different methods and ideas that attempt to deal with a large corpus of texts. Following this, we will present Roman Mafte’ach (literally: roman à clef),3 a new digital approach we have developed aiming to deal with the Hebrew novel as a whole. We will describe the questions that such an approach can give rise to and look at both its possibilities and limitations. We will conclude this contribution with a section devoted to our initial findings, as well as with a few of our reflections and further suggestions. Setting our new methodology within the larger frame of Digital Humanities, we wish to offer it as another bridge between traditional literary studies and the digital age.

3 The title of the project is therefore based on the professional name of a specific genre, but it makes secondary use of it, taking it out of the original context: the project has no special interest in the roman à clef per se, but in the concept ‘key’ that it includes, which, in Hebrew also indicates an index. The key, or index, is an important part of the project’s tasks, as we will demonstrate by and by.

2 Option #1: The Humanities and the Digitized Text

Indeed, there are ways to deal with great corpora, and projects in the humanities are able to respond to the challenges posed by them. Such projects, varied in discipline, scope and technique, strive to include a large number of texts as their source material; they approach these texts as containing data, that is

a digital, selectively constructed, machine-actionable abstraction representing some aspects of a given object of humanistic inquiry. (Schöch 2013; emphasis in the original)

Thus, the machine, determining the dominance of quantitative methods, plays a crucial part in such projects. The text being digitised is (almost always) a condition, enabling this kind of research.

A prime example lies in a study that was carried out by Michel et al., presented in their oft-quoted article mentioned above, “Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books” (Michel et al. 2011). Aiming to observe cultural trends through quantitative investigation, the authors used 5,195,769 digitised books; according to them, this is about 4% of all books ever written (176). The term ‘culturomics’ was coined by them to describe this form of computational lexicography which, using Google Ngram Viewer, focuses on culture and on human behaviour. A similar methodological approach was used in many subsequent studies in many fields: history, media, linguistics and, more relevant to our study, literature. Thus, most projects in computational literary studies (CLS) – a relatively new branch of literary criticism and one of the main subfields of the Digital Humanities – have heavily depended, especially since the turn of the twenty-first century, on big corpora of digitised texts analysed by means of computational processing. This is clear, for example, in the publications of the Stanford Literary Lab founded by Moretti and Jockers in 2009,4 and in the work of many other scholars and centres as can be seen in leading DH journals such as the Journal of Cultural Analytics (CA) that, in five years, has become one of the flagships in the field.

4 See, for example: Heuser, Le-Khac 2012.

The computational manipulations are many and different. Among others, topic modelling algorithms, one of the most popular tools in the field, were designed to identify groups of words that are often associated with each other, in pre-chosen digitised documents, providing “a compromise between full manual tagging and naïve word counting” (Mimno 2012, 9). Good examples of this are Jockers’ and Mimno’s analysis of 3,346 works of fiction from nineteenth century English literature, focusing on the authors’ sex and on gender-related themes (Jockers, Mimno 2013), and Andrew Goldstone and Ted Underwood’s observation of trends in literary theory and criticism (Goldstone, Underwood 2014) – a study which is based on more than 21,000 scholarly papers in literary history, written over the course of 120 years. Such solutions must be accompanied by additional techniques, of varying levels of technological and conceptual complexity: from the use of graph theory (Moretti 2011), through other non-naive word-counting applications such as TTR (type-token ratio), word clouds and more (Hammond 2016; Rockwell, Sinclair 2016), to manual annotation (Meister 2014) and alternative modes of data modelling (Flanders, Jannidis 2019) also adapted for literary analysis (Piper 2019) – the market of solutions is not small.

These options are available for any trained scholar who wishes to see cultural and stylistic trends in a large corpus of texts. The field is well established: this is almost a paved pathway. Though the prerequisite of the texts being digitised might be an obstacle, it is a technical (as well as legal) hindrance that is not insurmountable. And indeed, we have begun to enable such statistical measuring methodologies by archiving digitised versions of the Hebrew novel. Nevertheless, the platform we are proposing here is somewhat different. We will describe it in detail after surveying another, pre-computational, option.

2.1 Option #2: Distant Reading and the Canonical

The methodological approaches described above, varied as they might be, are often placed under the umbrella of ‘distant reading’. Thus, distant reading is usually seen today as any computational approach in literary studies (and related fields) that aims at a systematic consideration of a large corpus of texts without, necessarily, reading it at all. Therefore, distant reading (sometimes, and not necessarily) is identified with big data processing, with data visualisation, and more generally, with computer-dependent reading strategies that offer an alternative to traditional reading processes (Jänicke et al. 2015).

Nevertheless, a closer look at the first appearance of this concept, reminds us again that, back in 2000, computers were not included in its interpretive mission. Moretti published his groundbreaking article (Moretti 2000a) before entering the now-imperial kingdom of the Digital Humanities – or, to put it more simply, before he started using computers. A close reading of his distant reading approach might be conceptually useful here. Clearly, his corpus and its scope is different than ours: while Moretti was preoccupied with world literature, it is the (relatively small-scale) Hebrew novel that interests us. Yet the question remains the same: “The question is not what we should do – the question is how” writes Moretti, continuing by formulating that

world literature is not an object, it’s a problem, and a problem that asks for a new critical method: and no one has ever found a method by just reading more texts. (Moretti 2000a, 55; emphasis in the original)

The new critical method suggested by Moretti is distant reading, offering a new way to approach the field of literary studies. A lot has been written about this approach in its early pre-computational version, its strengths and importance to the emergence of Digital Humanities, as well as its weaknesses: Moretti’s model became a subject of much debate, seen as causing damage to what is sometimes perceived as the essence of the discipline (i.e. close reading of individual texts), as a model that is ‘not-accurate-enough’, and also as promoting western, English-language-oriented generalisations about third world literature (Arac 2012; Parla 2004). Later, as distant reading became more and more identified with computational analysis – a gradual and insinuative process, both in Moretti’s own work (2005, 2013) and in the way the concept was adopted (or not adopted) in the research of many others – it naturally provoked further criticism (Ross 2014; Kirsch 2014; Underwood 2017; Da 2019).

Although (or, perhaps, because) it was revolutionary and audacious, over twenty years after it was first suggested, there are still voices arguing that despite its significant achievements, the new paradigm has not resulted in a convincing combination of traditional research and technological perspectives. Some scholars admit that many typical projects of distant reading have not produced ‘great results’, failing to fulfil the potential of the model and disappointing also Moretti himself, who declared in an interview that “the results so far have been below expectations” (Dinsman 2016). As Adam Hammond explains:

[m]any distant reading projects have produced disappointing results because they have been more interested in validating their tools – showing that their computational methods are able to confirm existing stereotypes – than in pursuing genuine discoveries. Many others, meanwhile, produce provocative results that cannot be meaningfully validated. (Hammond 2017, 1)5

5 It is interesting to read this statement in light of the way Andrew Piper approaches the role of computational validation procedure in literary studies (2020).

This critical voice has had an impact. At this point it may be too early to characterise current computational attempts at distant reading, but it seems that at least some of them have taken the criticisms into account. More and more works in Digital Humanities call for reflective observations, ones that have a greater degree of self-criticism and self-awareness; all the while, the issue of size continues to be one of the focal points of the discussion (Underwood 2019; Dobson 2019; Jannidis 2019).

On the other hand, Moretti’s early distant reading does deal directly with the problem it was created to solve, that is, with the problem of size. Not through machine learning, but rather – and this point should be emphasised – through second-hand readings of different literary historians. In other words, his main argument is made possible by an exclusive reliance on canonical and authoritative historiographies. He explicitly writes that his intuitions about the modern novel were supported by the following literary historians:

Gasperetti and Goscilo on late eighteenth-century Eastern Europe; Toschi and Martí-López on early nineteenth-century Southern Europe; Franco and Sommer on mid-century Latin America; Frieden on the Yiddish novels of the 1860s; Moosa, Said and Allen on the Arabic novels of the 1870s; Evin and Parla on the Turkish novels of the same years; Anderson on the Filipino Noli Me Tangere, of 1887; Zhao and Wang on turn-of-the-century Qing fiction; Obiechina, Irele and Quayson on West African novels between the 1920s and the 1950s (plus of course Karatani, Miyoshi, Mukherjee, Even-Zohar and Schwarz). Four continents, two hundred years, over twenty independent critical studies, and they all agreed: when a culture starts moving towards the modern novel, it’s always as a compromise between foreign form and local materials. (2000a, 59-60)

However, historiographies – reliable as they may be – take into account the canonical novel within their respective literatures (be it Yiddish, Arabic or Filipino).6 They neither challenge the canon explicitly, nor do they venture out to “the great unread” to use the terminology of Margaret Cohen. Thus, although Moretti undermines the dominance of European literature through his reading of, inter alia, West African, Latin American and Turkish historiographies, by doing so he still replicates the literary canon, within these respective literatures.7

6 The very perception of the novel as a multi-faceted phenomenon underlies the comprehensive collection of articles edited by Moretti (2006); in a way, this is another reflection of his pre-digital distant reading approach. For a more unified perception on the development of the novel see Pavel (2015), who manifests another semi-distant-reading attitude. We believe that the two perspectives can add to each other, in the unique trajectory of the development of the Hebrew novel, including its complex relationship with the tradition of pre-modern Hebrew/Jewish literature.

7 For a broad look at the tension between local and global in the context of world literature and theory, see Damrosch 2003; Bar-Itzhak 2019.

Let us be reminded that studying the canon is, according to Moretti, close to “a theological exercise – very solemn treatment of very few texts taken very seriously” (2000a, 57). As demonstrated above, however, in the very same article Moretti in effect reflects on the canon of different literatures. “Conjectures on World Literature”, where the term ‘distant reading’ was coined, and where this idea was formulated, is where Moretti renounces both reading and the noncanonical in order to deal with size. As we will promptly see, in another article by Moretti, the noncanonical entered the picture differently, and using quite a different strategy. This time, reading – real reading – reclaimed its position.

2.2 Option #3: Distant Reading and the Noncanonical

In “The Slaughterhouse of Literature” Moretti is interested precisely in the question of the noncanonical; he proposes a change in our understanding of literary history, suggesting to look at both the canonical and the noncanonical (Moretti 2000b). With the help of students and research assistants he reads canonical and noncanonical detective stories, in order to discover the reason in their form for them being either read or unread. “Literary history is, and my thesis here is that what makes readers ‘like’ this or that book is – form”, writes Moretti, focusing his attention on a (relatively speaking, of course) narrow corpus: about 20 detective stories in one experiment, 108 mystery stories in another. Big enough, but not too big (Moretti 2000b, 211).

Clearly, distant reading is the method here, too, albeit in a different way: now Moretti does not rely on historiographies of literary texts, but on readings of the texts themselves, using a concise research question (concerning the clue as a literary device in canonical and noncanonical detective stories) and employing different readers who, in his words, comb the texts for clues (Moretti 2000b, 212). In “The Slaughterhouse” the distance from the text had shortened; though not close, this is still reading. The noncanonical remains a (big) part of the question, yet the scope – indeed, befitting Moretti’s task in this study – is nevertheless much smaller.

As far as we know, Moretti has not returned to such an approach. Distant reading split into two different – perhaps even in some sense opposite – directions, and this observation is accurate, generally speaking, with regard to the work of the major players in the field. Indeed, there were a few rare yet serious attempts to combine the humanised and the computationalized, with a commitment to the theoretical and practical challenges involved (Meister 2014). However, for the most part, the humanised has been taken out of the computationalized. This has a price, first pointed out fifty years ago by those engaged in computational literary research in its early days, a long time before Digital Humanities became a buzzword: one does not perceive ‘the text’ merely as words, one perceives it as a set of relationships between him or her, and the literary work. Even in the age of computers, we cannot forget, thankfully, what reader-response criticism has taught us,

whether the computer has been used in ways that significantly alter our view of the literary universe, or whether it has merely been used to show, in more distinct outline and with more substantiating data, what we already knew to be there,

wrote Susan Wittig long ago,

The major conceptual problem […] is the [computational] concept of the text […] [while] the text acquires meaning, or rather is fulfilled with meaning, only in the act of reading, in the creative encounter between the reader and the text. The text exists, not formally, on the page, but phenomenally, in the moment when the reader invests it with meaning and value that are partly dependent on the author’s direction. (Wittig 1977, 211-13)

What was true for Wittig 44 years ago is true for us today as well, even if the tools that we use now are much more sophisticated. How can the two concepts of the text be combined into one? How can we retain the scope including the noncanonical part, without renouncing the reading? Finally, how can we use computers to support, rather than replace, reading? A few approaches address these questions. One, developed by Jan Christoph Meister and his team, deals directly with this challenge, and is represented pragmatically in the annotation platform CATMA (Gius et al. 2020; see also Horstmann 2020). Quite a different one harnesses the computer to support the research of social reading, a term referring to reading practices carried out digitally in social media, or in specific platforms. In fact, these two approaches, though very different, open the door for multiple, human reactions and considerations of literary texts (Vlieghe et al. 2016; Gius, Jacke 2017; Rebora, Pianzola 2018). With these ideas in mind, we turn to present our Hebrew novel project in detail.

3 The Hebrew Novel in the Eyes of Many

The Hebrew novel, being both big-enough and small-enough, can be seen as a case-study by means of which one can examine answers to these methodological and conceptual questions. Analysing it with algorithmic tools is a feasible task (even if we have to put a lot of effort into finding and developing NLP solutions for Hebrew, which, like other Semitic languages, is morphologically and syntactically different than European languages). Validating the results manually, even only partially, is a feasible task as well. But such a corpus may offer an even greater opportunity: limited as it may be, it is an entire literary field, rather than a fragment artificially created for research purposes. We have not determined how the corpus will be defined; we have started from the very reality of it as a fact, as a promising fact. And we want to read it before it becomes too big.

And yet, reading 8,500 novels is a challenge, particularly if we do not want to reflect on them through second-hand hegemonic and canonic historiographers and critics; particularly if we want to include all of them, and not only the canonical and studied ones; and also not just understand them as, say, 3,000,000 pages that need to be processed by digital and computational means, ignoring the fact that these pages are “fulfilled with meaning, only in the act of reading” (in the words of Witting 1977).

With these challenges in mind, we decided to turn to the public, and to experiment with a new type of reading, a new concept if you will: that of public distant reading. We realised that, if we turned to the public, to broad communities of readers (not necessarily scholars of Hebrew literature), we would be able to address all of these issues. Through public reading, we will be able to cover, potentially, the entire corpus; we will be able to see beyond the canon, beyond the classics, and beyond the best-sellers; we will be able to get rid of hierarchies, both within the literary sphere of different sub-genres and other divisions, and also between our readers; and, as a cherry on the top, we will be able to gather hermeneutic-based knowledge that can deepen, and sometimes even contradict, any non-human computational attempt to analyse the material at a glance. In other words, turning to the public is a way of ensuring a broader scope as well as overall diversity, without paying the price of a non-reflective sampling of the texts in the corpus.8 Moreover, by bringing in non-professionals as reliable readers, the project is able to bridge the gap between academia and the public, igniting public interest in what is often considered ivory tower academic scholarship, and locating the novel (and its study) where it belongs: in society.

8 This approach, of course, is not unique to the study of Hebrew literature; it can be helpful in analysing any defined corpus of literary works, in any language.

The method chosen is quite simple, and is based on the following steps:

-

composing a comprehensive questionnaire that will be addressed to the general readership, expert and non-expert readers alike, and that will ask for as much information as possible (objective and subjective) about the Hebrew novel;

-

distributing the questionnaire among readers’ communities through electronic media, social networks and more;

-

collecting the questionnaires, sifting through the data and structuring it, then analysing it with statistical and visual tools;

-

validating fundamental objective elements that emerge from the questionnaires against more authoritative sources of information (see below);

-

at the same time, building a comprehensive digital corpus of the Hebrew novel, and analysing it with algorithmic tools based on the insights arising from an analysis of the questionnaires.

“Admittedly, contemporary distant reading is usually based on textual evidence, or on social evidence on dead people, rather than on questionnaires” writes Underwood in his “Genealogy of Distant Reading” (2017). And indeed, besides questionnaires-based studies in pedagogy (see, e.g., Miall, Kuiken 1995), we know of only one study that employed such a methodology: Janice Radway’s Reading the Romance (1984), a feminist, groundbreaking work of reader-response, centring on a community of readers using interviews and questionnaires. Yet the focus of Radway was, first and foremost, the readers, and the ways in which they understood romance novels, as opposed to the way that critics understood them (Underwood 2017). Although we can use our data also to learn about communities of readers, this is not the only outcome of our project, which aims at using reader responses as a means for the study of the novel. In a way, we are applying the conceptual promise of computational literary studies into the realm of human reader-responses, in order to have a better understanding of our chosen literary corpus: the Hebrew novel.

In Roman Mafte’ach, then, we use questionnaires to collect data on every novel originally published in Hebrew, from Ahavat Zion (The Love of Zion) published in Vilna in 1853 till today, both in Israel and elsewhere.9 Thus, the project is haphazard in its essence, as we ask that readers answer a questionnaire on any Hebrew novel they have recently read: both canonical and noncanonical novels; both popular and belletristic; novels published by well-known and commercial publishing houses, as well as ones that were published by independent, small ones; Hebrew novels throughout the generations, across the continents in which they were published. We assume that once we see the Hebrew novel as a distinct phenomenon, and once we gain enough data on Hebrew novels, we will be able to draw connections between different types of data concerning different aspects of the novel. These connections have the potential to power ideas and arguments, and can only be perceived through public distant reading, when approaching the Hebrew novel from above.

9 Our approach can be compared to CATMA, which is similar in its theoretical essence, but practically different, as we do not collect text-linked annotations, but general metadata about each novel as a whole.

3.1 Towards an Authoritative List of the Hebrew Novel

The anchor to this haphazard project is an inventory we compiled which includes all the titles and authors of the Hebrew novel, from Ahavat Zion to the present day. After a process of defining the large corpus, based on the catalogue of the National Library of Israel (which archives a copy of every book published in Hebrew, using the Library of Congress cataloguing system), we retrieved a list containing, supposedly, more than 13,000 novels. A thorough examination of this list revealed that many of the books that were included as novels are, in fact, essays, short story collections, textbooks, and more. We have automatically and manually sifted through the inventory, until arriving at a more-definitive list consisting of roughly 8,500 titles of Hebrew novels.10

10 As an anecdote, scholars with whom we spoke about the project in its early stages found it difficult to provide an estimation of the total number of Hebrew novels. Some indicated extremely low numbers, no more than 2,000 novels. Those who indicated the highest numbers spoke of no more than seven or eight thousand (a number relatively close to the one found in our inventory). These varied estimations point to the necessity of an authoritative and validated list, indicating the number of Hebrew novels; as is explicated earlier, such list became a central part of our project.

It is important to stress that the list includes data that does not exist elsewhere. This is because, up until our research, the Hebrew novel was not systematically catalogued as a distinct category in library catalogues and databases. The importance of this list is twofold: first, the inventory itself is a new source of data (mainly of bibliographical nature: titles, authors, year of publication, publishing house, number of pages). Thus, it answers several of the main questions posed when initiating the project, including the most crucial ones: how many titles make up the corpus of the Hebrew novel? And how are these titles distributed over time?11 Second, the list is useful for validating, as well as anchoring, some of the data we collect using the questionnaires.

11 An interesting one-answer question – who is the most prolific author of Hebrew novels? – receives a decisive answer, based on our inventory: it is Bert Witford, pseudonym of multiple authors who wrote in the sixties, seventies and eighties some 170 (!) Hebrew novels (and more precisely, detective stories and pulp fiction). These Hebrew-original novels where presented by the publishing house (and catalogued sometimes by librarians) as translations – a strange episode in the history of Israeli literature and culture, which is not the place here to discuss; in other words, 2% of the Hebrew novel belong to pseudo-translated works, which, from the common academic point of view, are perceived as inferior to have a place in the standard historiography of Hebrew literature.

This way, the decisiveness of one source of information balances the open nature of the other, and vice versa. To start with, some easy, one-answer-questions – ones that the data from our inventory can easily deal with – can be productive. Indeed, Moretti’s “Style, Inc.” (2009) devoted solely to titles, demonstrates how a distant reading of thousands of titles can include cultural, as well as methodological insights. However, our project, consisting of data from the inventory as well as the questionnaires, aims to combine these kinds of objective (or one-answer) questions with more subjective or interpretive ones. Thus, it is one thing to determine the length of the novels in the corpus; it is quite another to explore the relationship between length and plot. It is one thing to check which wars are mentioned in the novels; it is quite another to ask if they are important in the narrative structure at all. It is one thing to explore the linguistic register of the novel; it is quite another to examine its connection to the type of narrator. We could list more examples here, but the idea is clear enough: given the scale of data we collect, the number of questions that can emanate from this project, as well as their complexity – relying on possible combinations of different aspects of the Hebrew novel – is limited only by our imagination.12

12 These, of course, are only a few examples. In the end, many disciplines and subdisciplines can benefit from the project: narratology, Hebrew literature, Jewish culture, European history, as well as interdisciplinary studies that deal with the connections between belles-lettres, society and history.

3.2 There are Questions to be Asked

Some simple and necessary details: the questionnaire of Roman Mafte’ach is designed to collect data in several main categories, using multiple-choice questions, linear scales, and a few short-answer questions which allow for more personal and interpretive responses. We have designed the questionnaire with the general public in mind, and therefore we have added clear explanations next to every literary or professional concept included in the questionnaire. Moreover, we have left the option to skip any question not understood.

Later on, we will reflect on the question of pluralism versus a systematic interpretation. But an intrinsic tension should be noted: a project based on questionnaires, although widening the interpretive horizons, still limits and structures (by definition!) the possibilities of interpretation. Such tension is inevitable; nevertheless, in our opinion it is not undesirable. Since our focus here is less on the reading experience and more on the novels as mediated by readers, we have decided to pay the price of forming the questionnaire in a way that supports our focus.

The questionnaire consists of many questions in the following categories:13

13 We have decided to limit the number of questions, so filling out the questionnaire should take a maximum of 15 minutes.

-

Biography and bibliography

Name and sex of author, novel title, year of publication, position of the novel within the author’s oeuvre, publishing house, editor, number of pages.

-

Reception

The critical response the novel received, prizes (local and/or international) where applicable.

-

Structure

Sub-genre, graphic components, sub-structure of the novel, chapter length.

-

Narratological aspects

Type of narrator, narrator reliability, ‘eventful’ events, plotting, types of exposition and closure.

-

Language and reading experience

Grammatical tense, linguistic register, other languages used in the novel, inter-textuality, and readability.

-

Time and space

Temporal scope of the novel, main historical epoch, main space(s) in which events take place, main geographical area(s).

-

Themes

This part includes multiple-choice questions about many themes addressed by the Hebrew novel (e.g. love, family, childhood, marriage, physical illness, mental illness, crime, Judaism, Christianity, religiosity, war, sex, sexual identity, science and technology, climate change and more).

-

Personal assessment

This part includes a reflective question about the effectiveness of the questionnaire, as well as an open question that allows space for other ideas and topics not directly addressed in the questionnaire.

3.3 Tell Me What You are Reading and I’ll Tell You Who You are

Before we turn to examine some of our initial findings, a quick sociological insight, regarding the gap between academia and the public in the reception of our project, is called for. It should be said, without bitterness: so far, only one senior scholar responded to our call to participate in the research (one of 229 readers!) and only a few young scholars contributed by filling out a questionnaire. In private conversations, some of them expressed a real fear of recording insights from their research into the seemingly closed-ended templates of the questionnaire. Some even explicitly claimed that the project is ‘too innovative’ for them, or that they are no longer ‘at the right age’. As a result, the bulk of our readers consists of the general public, people who define reading as their hobby, rather than professional readers, alongside a significant group of young literature students.

This situation is also evident from the place of the project in the media: radio broadcasts and podcasts, local newspapers, news websites and even the Israeli edition of National Geographic, all were interested in including an item – or more than one – on Roman Mafte’ach. The continual interest from the media, as well as numerous appeals from readers whom we seek to involve in the research, reflect, yet again, the public nature of our project.

4 Initial Findings

From readers to novels: the findings below are preliminary by definition. They represent the first experimental stage in the gathering of material, allowing us to test the method: its effectiveness as well as its challenges. Given the length of the questionnaire and the complexity of the task our respondents agreed to take on themselves, we estimated and hoped that by now we would have data on no more than three hundred novels. We knew that some readers might be deterred by its length and complexity, but we have decided to maintain this relatively high bar as a threshold; after all, the questionnaires should be answered seriously and attentively. The answers, we assumed, would be enough to indicate initial trends and to reveal meaningful developments. And happily, within fourteen months, 525 questionnaires were collected, filled out by 229 readers, who covered in total 386 novels. What we have here is data on roughly 4.5% of the Hebrew novels ever published – assuming the total number of novels is 8,500, as indicated by our inventory. Good enough for a start. Consistently and persistently, we cover more and more sections of the Hebrew novel. We do not end here, of course: we are continuing to disseminate the questionnaires to as many readers as possible, including professional ones for more-specific reading tasks (as we explain below).

Preliminary as they were, the findings were astonishing: many scholars must have read more than 300 novels in their professional lives, guided by specific research questions or any other personal interest, but no one has seen them the way we, now, can see them. No one, as far as we know, could outline an empirical picture obtained from accumulating synchronously so much data that is both comprehensive and random – in the positive sense of the word.

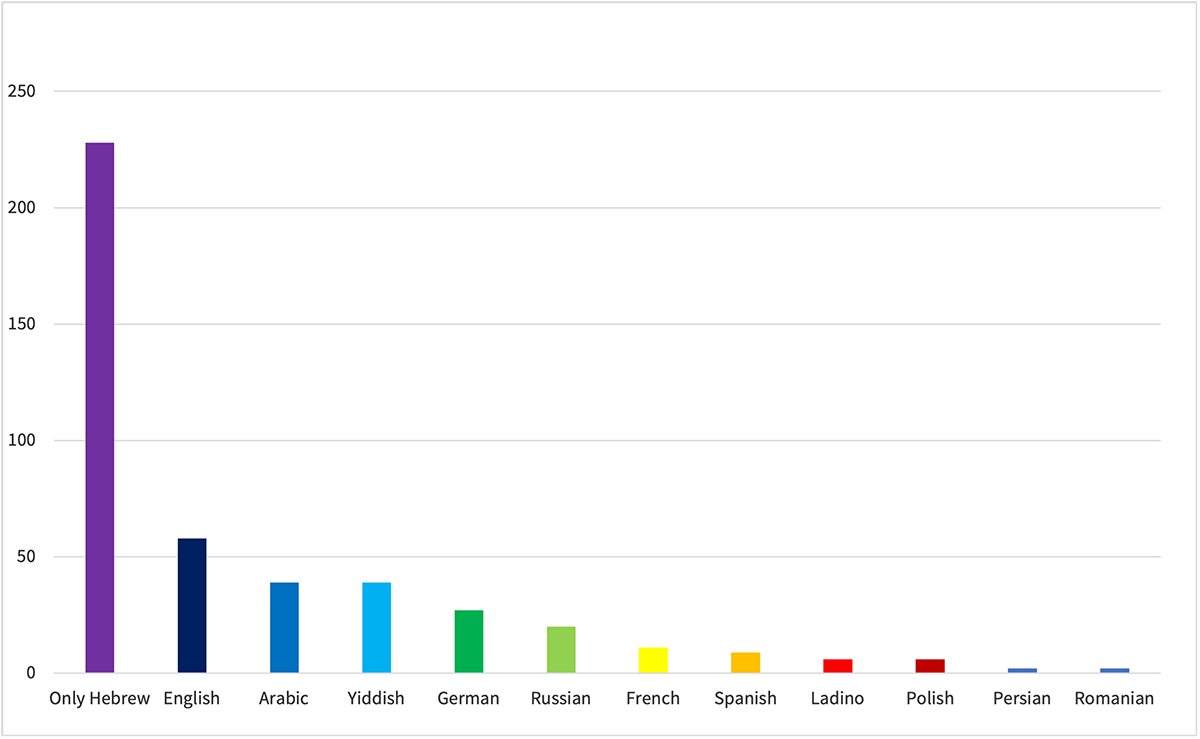

For example, none of them could say with as much clarity as we can now, that the variety of languages represented in the Hebrew novel encompasses within it intense cultural and historical tensions. It should be noted, for instance, that the most prominent language after Hebrew is English (and not Arabic, as one might have presumed); that Yiddish is ahead – quantitatively – of German; and that both of these are far ahead, quantitatively, of a distinctly Jewish language like Ladino [graph. 1]. At least in the case of languages in the Hebrew novel, even if a later picture is different, we can cautiously estimate that the difference will not be dramatic.

Graphic 1 Languages in the Hebrew Novel

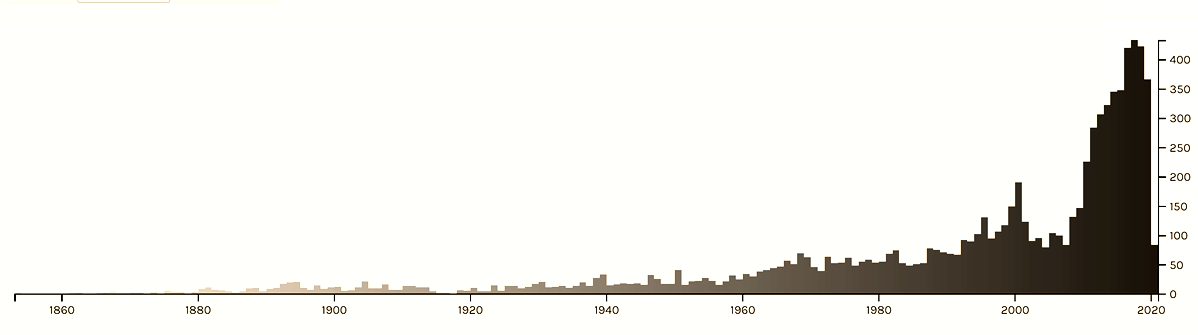

This figure, in itself, does not indicate any processes of development. The picture is static, unreflective of the history of, say, the emergence of English in the Hebrew novel, or the influence of other cultures (German, Russian, American, etc.), each in turn, on the Hebrew republic of letters. As the study progresses, we aim to show such developments. Moreover, since we asked the general public to fill out a questionnaire based on a novel that they have recently read, it is contemporary literature that is absolutely dominant in our database. As the following illustration shows, among the 525 questionnaires that have been collected so far as part of the project, a powerful bias towards the literature of the last twenty years is evident [graph. 2a].

Graphic 2a Timeline: Year of Publication of the Novels read in Roman Mafte’ach, updated to August 2021

The timeline that emerges from the questionnaires should be examined against the timeline that emerges from the full authoritative list of 8,500 novels [graph. 2b]; then, what seemed biased is actually seen as more accurate, as the two graphics reflect the uneven distribution of novels over time, with a notable peak in the last decade.

Graphic 2b Timeline: The Distribution of the Hebrew Novel over the Years

On the other hand, this bias, which must, of course, be taken into account when analysing the results, has also accentuated what is a very real and practical challenge: the general public does not guarantee direct and equal access to all kinds of knowledge. Clearly, contemporary readers tend to read recently published novels more than old ones. A lot can be learned from this about the reading habits of our readers (are there any other parameters – not only the time of publication – that influence the scope of reading today?). However, since our primary interest is in the Hebrew novel as a whole, we are encouraging professional readers (students, colleagues, research assistants) to fill in the gaps in our developed timeline.

Focusing on the range of years that is most represented in our data, some intriguing phenomena begin to emerge, things to examine in more depth in later stages of the project: when do Hebrew writers (avant-garde, probably) begin to use non-textual elements as part of the plot itself, not as an ‘external’ decoration to it, and not as part of the graphic novel? The answer, according to preliminary findings is, not before the last decade of the twentieth century. How does the typical graphic structure of a page in a novel change over time? According to the same preliminary data, it seems like in the mid-eighties some diversity began to form, with the ‘classic’ page (divided into paragraphs) taken over by two inverted page-models, one compact and dense, and the other spacious and airy. According to our readers, these are also the years in which the dominance of the omniscient extradiegetic narrator shifted, making way for the diegetic narrator, who is involved in the plot to some degree.

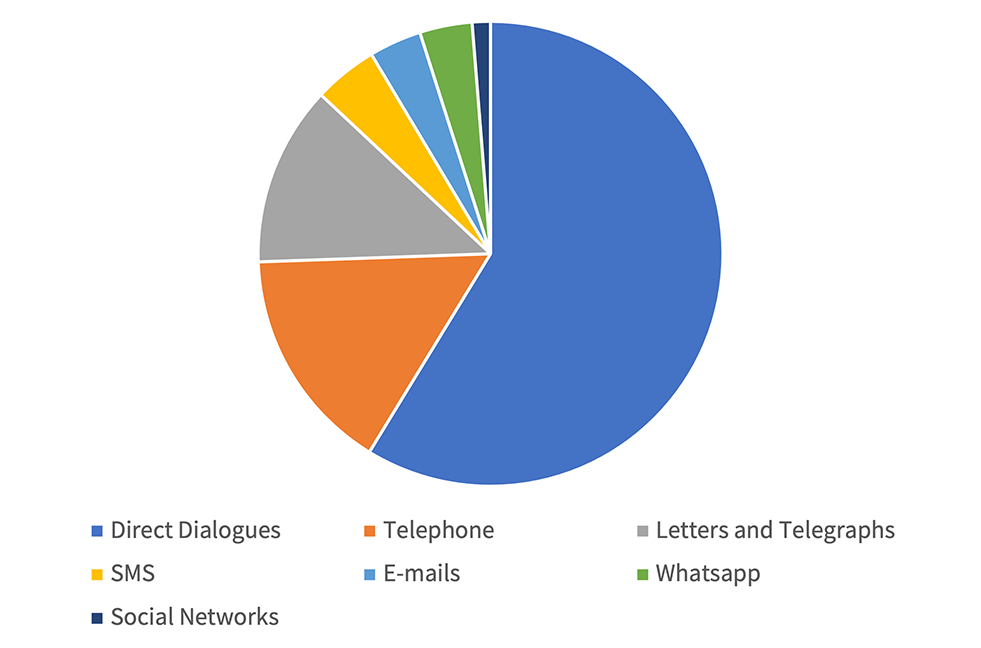

These findings still require future comparisons with earlier periods of the Hebrew novel. But some findings became even more significant than expected, precisely due to the proliferation of contemporary literature in our database. Among other things, in our questionnaire we examine the extent to which contemporary forms of human communication (emails, SMS, social networks etc.) are reflected in the novel – and the result was quite low: strangely, even books of the twenty-first century find it very difficult to translate our ultra-technological daily life into a mimetic representation [graph. 3].

Graphic 3 Communication in the Hebrew Novel

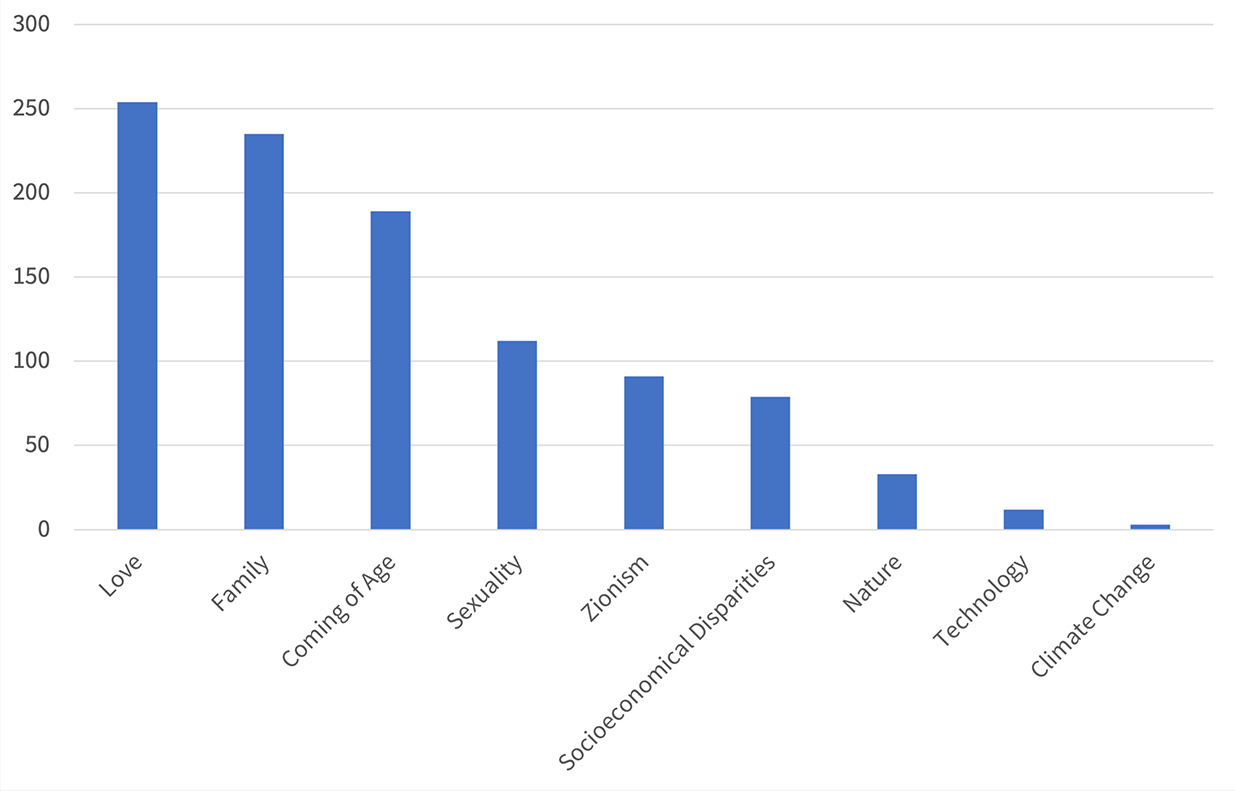

Moreover, as shown in the next figure, technology as a subject is almost non-existent in the data collected [graph. 4]. Not to mention the climate crisis, which, though a recurrent topic in the news at the beginning of our current millennium, is not reflected as such in the data. True, Hebrew writers are writing and publishing in the present; and yet according to our relatively rich data, it seems that they either do not see ‘the now’ or they do not give it an artistic mantle. The latter phenomenon was documented in contemporary novels in general, as brilliantly shown by Amitav Ghosh (2016).

Graphic 4 Themes in the Hebrew Novel (Selected Categories)

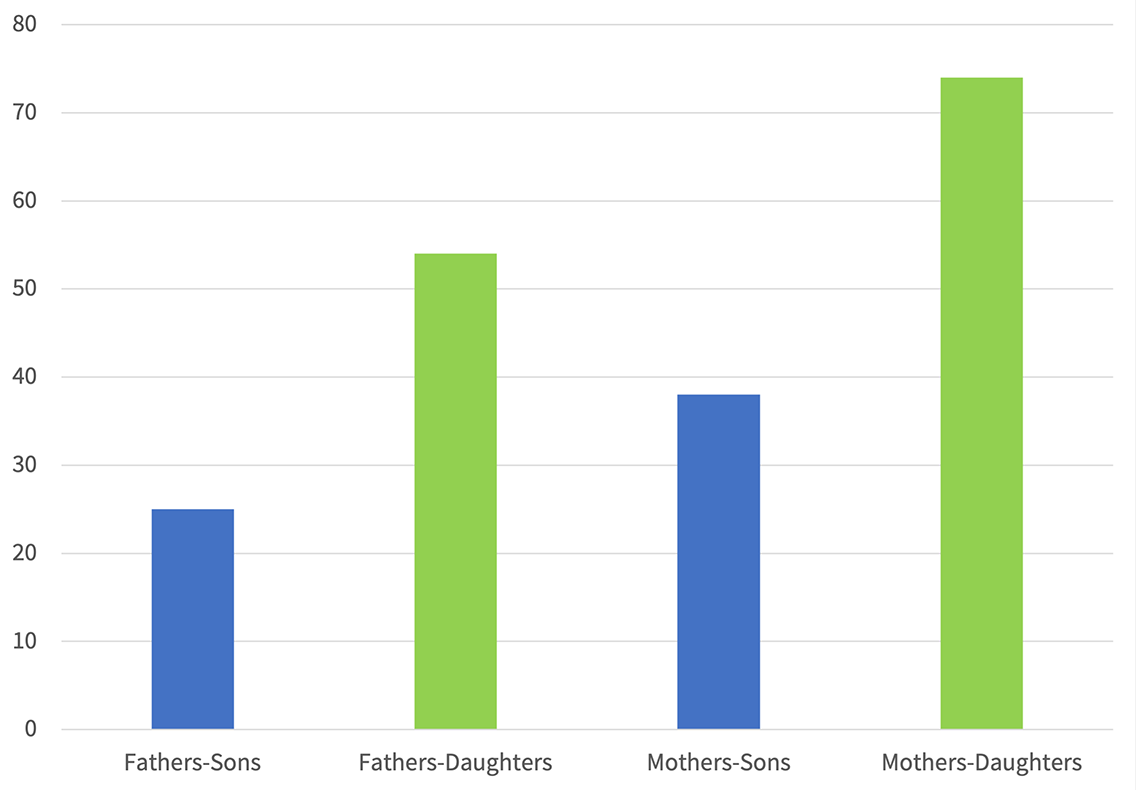

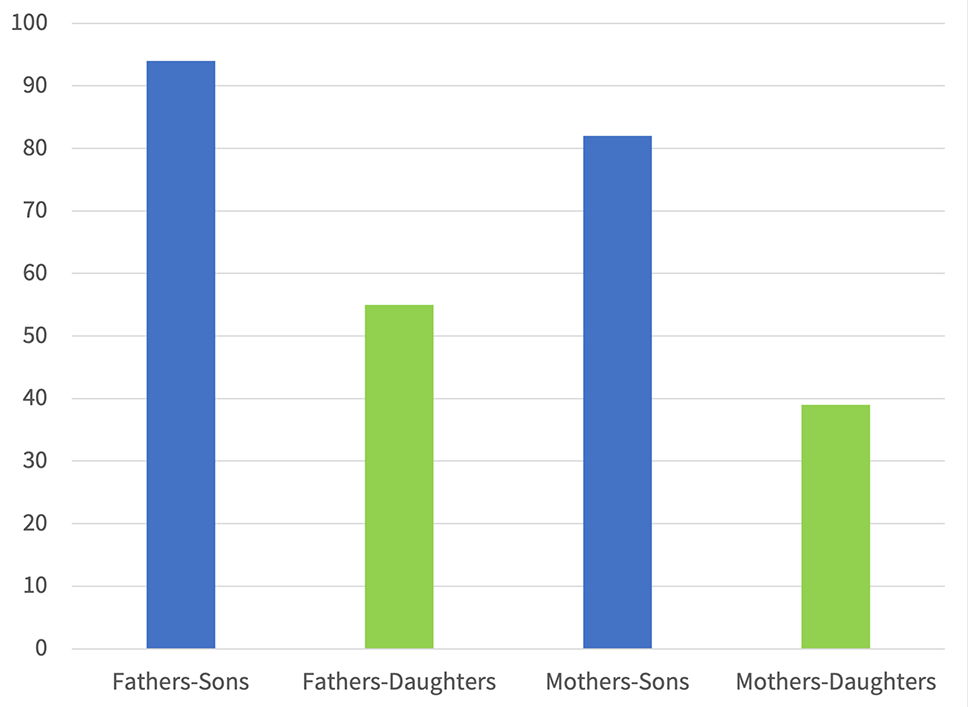

Some of our data show, also, a clear picture of the correlation between the intergenerational relationship within the family, and the sex of the novel’s author. As shown in the graphics, women authors write more about daughters (and their relationships with fathers and mothers) while men write more about sons (and their relationships with fathers and mothers) [graphs 5-6]. It might not be surprising; we can assume that, in general, different people tend to write on what is like them. However, grounding this notion in facts, and being able to make correlations between this and other issues (for example: themes that women or men write on, the average page number for each, and more) can help to gain significant insights, and to make larger arguments about human culture in general.

Given, for instance, the fact that more novels are written by male than by female authors (as shown in our database), the overall result of the intergenerational relationships question is that in every parameter the male is the focus of literary attention during the history of Hebrew novel: consistently, more fathers-sons relationships are represented than fathers-daughters relationships; more mothers-sons relationships are represented than mothers-daughters relationships. And surprisingly, the exact same result is obtained in third-generation relationships as well: more grandparent-grandchild relationships are represented than grandparent-granddaughters, and more grandmothers-grandchildren relationships than grandmothers-granddaughters.

Graphic 5 Intergenerational Relationships: Female Authors

Graphic 6 Intergenerational Relationships: Male Authors

Our task is a big one for traditional methods, a humble one for computational ones. Since it is big, the current picture is partial and modest. But since this picture is also a humble one, it has become fruitful in spite of the difficulties.

One difficulty lies in the very basic notion of trust. We often get asked: “do you trust your readers? How come?”. Going over each questionnaire, on some rare occasions we do find mistakes: one who filled out a questionnaire about a translated novel (whose original language is not Hebrew), or another who included a children’s novel (a sub-genre we have decided to leave out of the project). But such innocent mistakes are easily fixed by erasing the redundant data. So yes, in general we trust our readers, and the quality of data that we collect once and again vouches for them. In addition, the inventory mentioned above provides a source of validation, anchoring at least a part of the questions in our questionnaire.

The following is more challenging: we will happily receive multiple questionnaires on any one novel. Interestingly, and predictably, such questionnaires are almost never identical – at least in the more complicated and interpretation-dependent questions. Although this is quite confusing, we are not treating it as a threat to the methodology. True, we are extra-cautious when attempting to include this information in standardised graphs. But apart from this, we celebrate the difference, the multiplicity, going over the different readings and appreciating the smaller, as well as the larger differences, as they imply different readings, different points of view, different opinions. Indeed, as traditional, close and human reading is: you can never read the same novel the same way twice, you can never read it the way your friend does, the way your colleague does. Moreover, we see it as an opportunity to examine our questionnaire, as well as some of the concepts in narratology and in the study of Hebrew literature.

The final section of Moretti’s paradigmatic article includes a manifesto calling for intellectual attempts to reach the great unread by developing new, audacious methodologies. We quote this final paragraph here, as we see our project as an answer – even if only partial, as answers tend to be – to Moretti’s call.

Fantastic opportunity, this uncharted expanse of literature; with room for the most varied approaches, and for a truly collective effort, like literary history has never seen. Great chance, great challenge (what will knowledge indeed mean, if our archive becomes ten times larger, or a hundred), which calls for a maximum of methodological boldness: since no one knows what knowledge will mean in literary studies ten years from now, our best chance lies in the radical diversity of intellectual positions, and in their completely candid, outspoken competition. Anarchy. Not diplomacy, not compromises, not winks at every powerful academic lobby, not taboos. Anarchy. Or as Arnold Schoenberg once wonderfully put it: the middle road is the only one that does not lead to Rome (Moretti 2000, 227; emphasis in the original).

Radical diversity; anarchy; collective effort; diversity of intellectual positions; varied approaches. All of these – diversity, anarchy, varied approaches – are here, all are interesting. True, all of these do not make the study any easier, but once this messy data – again, in the positive sense of the word – is before our eyes, it is hard to ignore it.14

14 In recent years, Digital Humanities seem to be more and more aware of the questions of the discipline in its global context, as reflected, for example, in the forthcoming publication of a special volume dedicated to the issue, as part of the influential series Debates in the Digital Humanities (Fiormonte, Ricaurte, Chahudhuri, forthcoming). We see our project as a modest contribution to this important development.

5 Conclusions

At first it might seem as if what has been proposed here is nothing but a technical solution to a conceptual problem: the problem of size. But we are hopeful that, on second glance, things will take on a different aspect, and it will become possible to realise the potential of our approach. In a way akin to algorithmic practices, dealing with literature indirectly, reading (or, unreading) it through the lenses of others, has the potential to miss direct contact with the text itself. But unlike in the case of those practices, whoever chooses the approach proposed here will not give up on human (unmediated) contact with the text. In other words, distant public reading actually returns the reader’s interpretive sensitivity to the picture. Here, we do not extract literary, thematic, or structural insights from word clouds, or from vector representations of words in an abstract space; rather, we listen to what many readers have to say – through our structured yet broad questionnaire – even if that information is ‘dirty’, contradictory and confusing. We do not take the human out of the humanities: those who read the novels are human beings (not machine-learning algorithms); those who make the combinations and ask the questions are human beings, too; those who interpret the data, who perform the distant reading that this project enables, are human beings who wish to see the field from a distance. These human beings harness the technological processing and analytics for this task. A balanced quantitative, computational approach helps us to ground our intuition in data – graphs, numbers, percentages – without leaving the readers and scholars outside of the interpretive picture. Therefore, we cannot – we must not – expect human insights to be clean. Along with the many novels, there will be many readers, and therefore also many questions and answers.

This is also the case with the scope of the multiple possibilities which our approach opens: it does not contradict, prevent or limit other attempts in the humanities. In fact, it may aid them: first, as a tool for detecting and sorting phenomena in literature, and second, on a broader level, it can serve as a reference to be compared with other approaches. Thus, it encourages ‘traditional’ scholars to continue to define a smaller corpus, based on the questionnaires; at the same time it encourages DH researchers to continue on their own way – without reading – but through a thorough comparison of their computational findings with what emerges from the questionnaires. Roman Mafte’ach suggests an on-going, additive, and changing discussion, one which is intellectual (and public), humanist (and proven), thought provoking (and grounded in facts).

We want to read as many novels as possible, but we have not reached world literature; we remain within the bounds of our language literature, which is seen also as national literature. However, within the boundaries of this national literature, we have chosen the broadest common denominator – that of language which has no actual boundaries.15 Since Hebrew literature has always been written in different centres around the world making contact with different cultures, one might say that the borders in question are, in a sense, loose: they are not limited to the actual territorial boundaries of the nation-state (which, in many cases, are artificial with respect to culture); and nor are they restricted to the national, ethnic or religious origin of the author. “Our philological home is the earth; it can no longer be the nation”, wrote Auerbach ([1952] 1969, 17) beautifully, acknowledging that the task of world literature, in a world of nation-states, physical borders and national literatures, is not an easy one.

15 It will be fascinating to see our findings on the backdrop of other language-literatures; to be able to compare and contrast, in order to get to broad cultural observations and insights. From the point of view of world literature, it would be a promising endeavour. Despite that, such attempts to compare are rare and challenging. See, for example, Wilken 2021.

Bibliography

Arac, J. (2012). “Anglo-Globalism?”. New Left Review, 16, 35-45.

Auerbach, E. [1952] (1969). “Philology and ‘Weltliteratur’”. Transl. by M. and E. Said. The Centennial Review, 13(1), 1-17.

Bar-Itzhak, C. (2019). “Intellectual Captivity: Literary Theory, World Literature, and the Ethics of Interpretation”. Journal of World Literature, 5(1), 79-110. https://doi.org/10.1163/24056480-00403400.

Best, S.; Marcus, S. (2009). “Surface Reading: An Introduction”. Representations, 108, 1-21.

Cohen, M. (1999). The Sentimental Education of the Novel. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Da, N.Z. (2019). “The Computational Case against Computational Literary Studies”. Critical Inquiry, 45, 601-39. https://doi.org/10.1086/702594.

Damrosch, D. (2003). What is World Literature? Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Dinsman, M. (2016). “The Digital in the Humanities: An Interview with Franco Moretti”. LA Review of Books. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/the-digital-in-the-humanities-an-interview-with-franco-moretti/.

Dobson, J.E. (2019). Critical Digital Humanities. The Search for a Methodology. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Fiormonte, D.; Ricaurte, P.; Chahudhuri, S. (eds) (forthcoming). Global Debates in the Digital Humanities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

Flanders, J.; Jannidis, F. (eds) (2019). The Shape of Data in Digital Humanities: Modeling Texts and Text-Based Resources. London and New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315552941.

Gius, E.; Jacke, J. (2017). “The Hermeneutic Profit of Annotation: On Preventing and Fostering Disagreement in Literary Analysis”. International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing, 11, 233-54. https://doi.org/10.3366/ijhac.2017.0194.

Gius, E. et al. (2020). CATMA 6.1. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1470118.

Goldstone, A.; Underwood, T. (2014). “The Quiet Transformations of Literary Studies: What Thirteen Thousand Scholars Could Tell Us”. New Literary History, 45(3), 359-84. https://doi.org/10.1353/nlh.2014.0025.

Ghosh, A. (2016). The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hammond, A. (2016). Literature in the Digital Age: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hammond, A. (2017). “The Double Bind of Validation: Distant Reading and the Digital Humanities’ ‘Trough of Disillusionment’”. Literature Compass 14, e12402, https://doi.org/10.1111/lic3.12402.

Heuser, Ryan; Le Khac, Long (2012). “A Quantitative Literary History of 2,958 Nineteenth-Century British Novels: The Semantic Cohort Method”. Stanford Literary Lab Pamphlet 4 [online]. https://litlab.stanford.edu/LiteraryLabPamphlet4.pdf.

Holtzman, A. (1990). “A Junction in the Rise of the Hebrew Novel” [in Hebrew]. Dapim lemehkar besifrut, 7, 111-24.

Horstmann, J. (2020). “Undogmatic Literary Annotation with CATMA: Manual, Semi-automatic and Automated”. Nantke, J.; Schlupkothen, F. (eds), Annotations in Scholarly Edition and Research. Berlin; Boston: De Gruyter, 157-75. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110689112-008.

Jänicke, S. et al. (2017). “Visual Text Analysis in Digital Humanities”. Computer Graphics Forum, 36, 226-250. https://doi.org/10.1111/cgf.12873.

Jannidis, F. (2019). “On the Perceived Complexity of Literature: A Response to Nan Z. Da”. Journal of Cultural Analytics. https://doi.org/10.22148/001c.11829.

Jockers, M.L. (2013). Macroanalysis: Digital Methods and Literary History. Urbana; Chicago; Springfield: University of Illinois Press. https://doi.org/10.16995/dscn.62.

Jockers, M.L.; Mimno, D. (2013). “Significant Themes in 19th-century Literature”. Poetics, 41, 750-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2013.08.005.

Kirsch, A. (2014). “Technology is Taking Over English Departments: The False Promise of the Digital Humanities”. The New Republic. http://www.newrepublic.com/article/117428/limits-digital-humanities-adam-kirsch.

Manovich, L. (2020). Cultural Analytics. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Marienberg-Milikowsky, I. (2019). “Beyond Digitization? Digital Humanities and the Case of Hebrew Literature”. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 34(4), 908-13. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqz010.

Meister, J. Ch. (2014). “Toward a Computational Narratology”. Agosti, M.; Tomasi, F. (eds), Collaborative Research Practices and Shared Infrastructures for Humanities Computing. Padova: CLEUP, 17-36.

Miall, D.S.; Kuiken, D. (1995). “Aspects of Literary Response: A New Questionnaire”. Research in the Teaching of English, 29(1), 37-58.

Michel, J.-B. et al. (2011). “Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books”. Science, 331, 176-82. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1199644.

Mimno, D. (2012). “Computational Historiography: Data Mining in a Century of Classics Journals”. Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage, 5(1), 1-19.

Miron, D. (1979). The Rise of the Modern Novel, in Yiddish and Hebrew [in Hebrew]. Jerusalem: Mosad Bialik.

Miron, D. (2010). From Continuity to Contiguity: Toward a New Jewish Literary Thinking. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Moretti, F. (2000a). “Conjectures on World Literature”. New Left Review, 1, 54-68.

Moretti, F. (2000b). “The Slaughterhouse of Literature”. Modern Language Quarterly, 61(1), 207-27.

Moretti, F. (2005). Graphs, Maps, Trees: Abstract Models for a Literary History. Brooklyn: Verso.

Moretti, F. (ed.) (2006). The Novel. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Moretti, F. (2009). “Style, Inc. Reflections on Seven Thousand Titles British Novels, 1740-1850”. Critical Inquiry, 36(1), 134-58. https://doi.org/10.1086/606125.

Moretti, F. (2011). “Network Theory, Plot Analysis”. Stanford Literary Lab Pamphlet, 2. https://litlab.stanford.edu/LiteraryLabPamphlet2.pdf.

Moretti, F. (2013). Distant Reading. London; New York: Verso.

Netanel, L. (2016). “Mendale’s Time” [in Hebrew]. Iyunnim, 26, 280-300.

Parla, J. (2004). “The Object of Comparison”. Comparative Literature Studies, 41(1), 116-25. https://doi.org/10.1353/cls.2004.0011.

Pavel, T.G. (2015). The Lives of the Novel: A History. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Piper, A. (2018). Enumerations: Data and Literary Studies. Chicago; London: The University of Chicago Press.

Piper, A. (2020). Can We be Wrong? The Problem of Textual Evidence in a Time of Data. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108922036.

Radway, J. [1984] (1991). Reading the Romance: Women, Patriarchy, and Popular Literature. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. https://doi.org/10.1177/003232928501400111.

Rebora, F.; Pianzola, S. (2018). “A New Research Programme for Reading Research: Analysing Comments in the Margins on Wattpad”. Digitcult @Scientific Journal on Digital Cultures, 2(3), 19-36.

Ramsay, S. (2011). Reading Machines: Toward an Algorithmic Criticism. Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

Rockwell, G.; Sinclair, S. (2016). Hermeneutica: Computer-Assisted Interpretation in the Humanities. Cambridge: The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7202/1048829ar.

Ross, S. (2014). “In Praise of Overstating the Case: A Review of Franco Moretti, Distant Reading”. Digital Humanities Quarterly, 8(1).

Schöch, C. (2013). “Big? Smart? Clean? Messy? Data in the Humanities”. Journal of Digital Humanities, 2(3). http://journalofdigitalhumanities.org/.

Schwartz, Y. (2005). Vantage Point [In Hebrew]. Or Yehuda: Dvir.

Shaked, G. [1977] (2000). Modern Hebrew Fiction. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Underwood, T. (2017). “A Genealogy of Distant Reading”. Digital Humanities Quarterly, 11(2). http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/11/2/000317/000317.html.

Underwood, T. (2019). Distant Horizons: Digital Evidence and Literary Change. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.1086/707111.

Vlieghe, J. et al. (2016). “Everybody Reads: Reader Engagement with Literature in Social Media Environments”. Poetics, 54, 25-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2015.09.001.

Wilkens, M. (2021). “‘Too isolated, too insular’: American Literature and the World”. Journal of Cultural Analytics, 6, 52-84. https://doi.org/10.22148/001c.25273.

Wittig, S. (1978). “The Computer and the Concept of Text”. Computer and the Humanities, 11(4), 211-15. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30199899.