New Field, Old Practices: Promises and Challenges of Public History

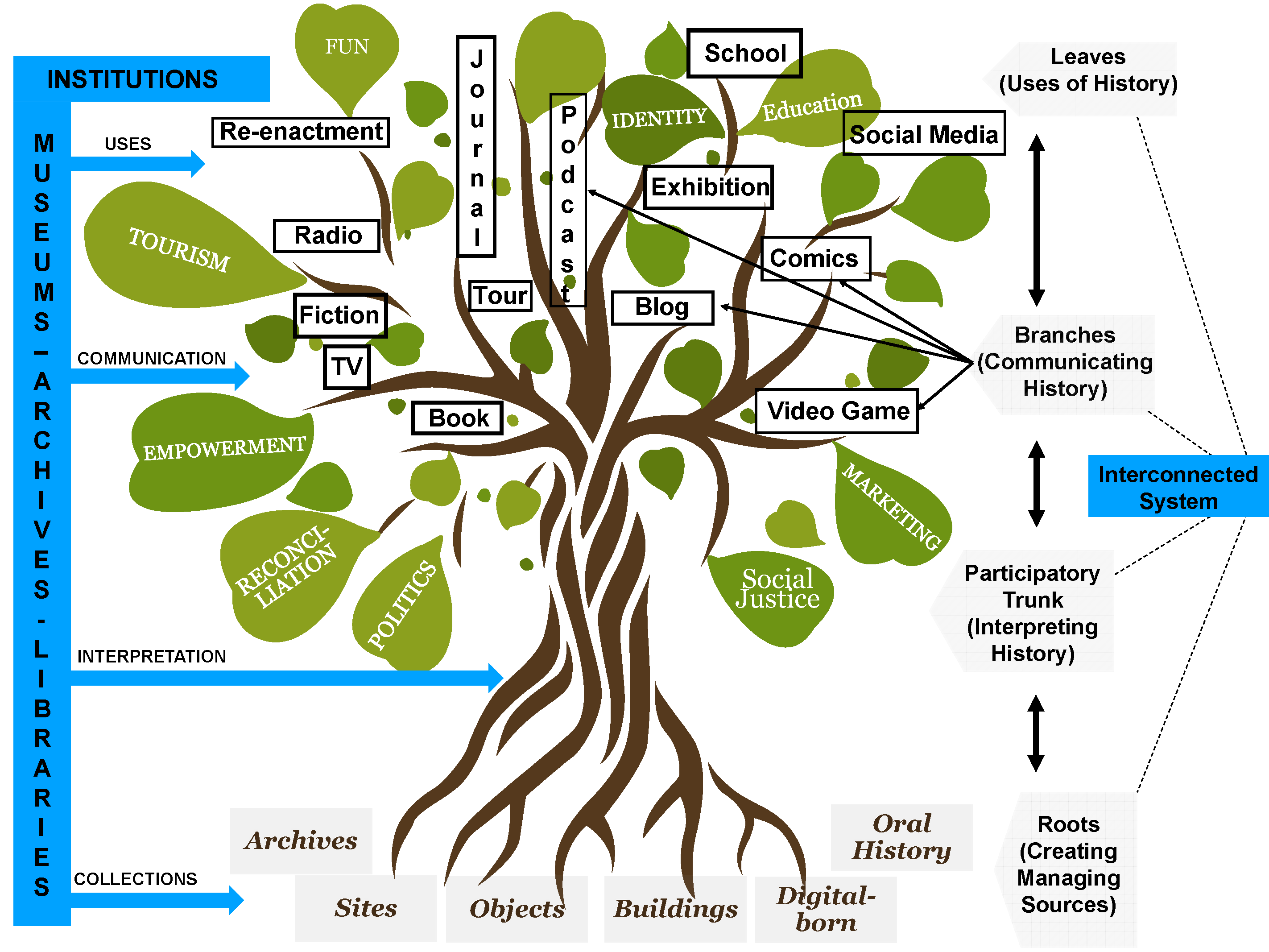

Abstract Although public history is becoming increasingly international, the field remains difficult to define and subject to some criticism. Based on sometimes long-established public practices, public history displays new approaches to audiences, collaboration and authority in history production. This article provides an overview of public history, its various definitions and historiography, and discusses some of the main criticisms of the field. Public history is compared to a tree of knowledge whose parts (roots, trunk, branches and leaves) represent the many collaborative and interconnected stages in the field. Defining public history as a systemic process (tree) demonstrates the need for collaboration between the different actors – may they be trained historians or not – and aim to focus on the role they play in the overall process. The future of international public history will involve balancing practice-based approaches with more theoretical discussions on the role of trained historians, audiences and different uses of the past.

Keywords Public history. Historiography. Collaboration. Memory. Ethics. Training.

Let us be honest; despite recent developments in the field, public history remains largely unknown outside the circles of its practitioners. If we explain that we practise, study or work with public history, our interlocutors are likely to raise their eyebrows, confess their ignorance and ask for more details. Once we explain what we do and why we practise public history, our interlocutors may easily find examples of their own, or even acknowledge – if they work in the field – that they have been working with public history without knowing it. The rise in public history comes partly from its long-established practices. Public history is built on an apparent paradox: it is a new field based on old practices. And the fact that public history includes old practices is also a sign of the times; it reflects a changing context in the ways we preserve, research, interpret, study, communicate, use and consume the past. One of the most visible changes, the rise and use of the Internet, has revolutionised how people access and communicate knowledge. History is not immune to these profound changes, nor should it be. Questions such as who owns the past, what role historians play and who can call themselves historians are an integral part of the debates on public history. As the field of public history is becoming increasingly international – see for instance the 2020 World Conference of Public History in Berlin, Germany – it seems timely to question how, and if, one should define public history. This article proposes an overview of the field, presenting its historiography, the reasons for its success and some criticism.

1 Public History: A Field Full of Promise

The term public history has often been associated with the United States, where it was first coined in the 1970s. The National Council on Public History (NCPH) – the main organisation for public history in the US – lists more than 200 programmes in the country.1 The number of programmes is such that some started to wonder if the competition between them would become an issue (Weyeneth 2013).

This article is the English translation of: “Campo nuevo, prácticas viejas: promesas y desafíos de la historia pública”, published in Hispania Nova. Primera Revista de Historia Contemporánea, núm. 1 extra, 2020, 7-51.

1 See the NCPH website, http://ncph.org/program-guide/. Unless otherwise noted, all the webpages cited in the article have been accessed on 20 January 2021.

Yet public history is not limited to the US or North America. Public history projects, programmes and conferences exist in many European countries and also in Brazil, Australia, New Zealand, Russia and China. The International Federation for Public History (IFPH), set up in 2011, aims to connect projects, professionals, students and other practitioners worldwide.2 The IFPH’s Call for Presentation for its 2018 annual conference in Sao Paulo, Brazil, attracted 54 individual papers and 15 panel submissions, with 92 authors from 26 countries around the world [fig. 1]. National public history associations have also been set up in Brazil (Rede Brasileira de História Pública), in Italy (Associazone Italiana di Public History, AIPH) and more recently in Japan (パブリックヒストリー研究会), attesting to the development of the field.3 Publishers propose textbooks, collections of essays, handbooks and companions in English, Portuguese, Italian, German, Polish, Chinese and Spanish (Cauvin 2016; Gardner, Hamilton 2017; Dean 2017; Mauad, De Almeida, and Santhiago 2016; Lucke, Zundorf 2018). Peer-reviewed journals – still a ranking criterion for research and publication – now specialise in public history too. The Public Historian, Public History Review, International Public History, and to some extent Public History Weekly, demonstrate that public history has reached a level of academic recognition.4

2 See the IFPH website, https://ifph.hypotheses.org.

3 See the Rede Brasileira de História Pública (“Rede” – RBHP) website, http://historiapublica.com.br, the AIPH website, https://aiph.hypotheses.org, and the website for the Japanese association, https://public-history9.webnode.jp.

4 The Public Historian, https://tph.ucpress.edu; Public History Review, https://www.uts.edu.au/public-history-review; International Public History, https://www.degruyter.com/view/j/iph; Public History Weekly, https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com.

While it is clear that public history is becoming increasingly international, defining the field remains challenging and open to discussion. For instance, the website of the 2020 World Conference of Public History does not provide a definition of public history. The IFPH itself only points out that international public history is “a field in the historical sciences made up of professionals who undertake historical work in a variety of public and private settings for different kinds of audiences worldwide”.5 The least we can say is that the meaning is (purposefully) unclear.

5 See the IFPH website, https://ifph.hypotheses.org.

Figure 1 Participants at the 2018 IFPH Conference in Sao Paulo, Brazil (Lucchesi 2018)

2 Do We Need – or Want – a (Single) Definition of Public History?

In his 2008 article “Defining Public History: Is It Possible? Is it Necessary?”, Robert Weible pointed out that “For all the talk of public history that we have been hearing for more than 25 years, it is a little awkward that historians are still uncertain about what ‘public history’ might actually mean. So perhaps it is fruitless to seek consensus on a single definition” (Weible 2008). I would argue that much more than a categorical, ultimate, single definition of public history, what we need is international discussions, exchanges and collaboration on what public history can become. Very much like the collaborative aspect of public history, defining the field should include various understandings, practices and theories.

2.1 Because Public History is not Like Pornography, “I Do not Know It When I See It”: Reasons for Defining Public History

If we recognise that public history is a subfield of historical studies, then we can look at other historical fields for inspiration. For instance, the Oral History Association proposes a definition of oral history as “a field of study and a method of gathering, preserving and interpreting the voices and memories of people, communities, and participants in past events”.6 Even though oral history is more established and more widespread than public history, this supports the idea that we need a definition of the field.

6 Oral History Association website, https://www.oralhistory.org/about/do-oral-history/.

The fact that public history is relatively unrecognised could also provide momentum for a clearer definition. Based on the 2009 NCPH survey undertaken among public history professionals, John Dichtl and Robert Townsend wrote that “Public history is one of the least understood areas of professional practice in history because the majority of public history jobs are outside of academia” (Dichtl, Townsend 2009). In the introduction to the 2018 keynote lecture at the NCPH annual conference in Hartford, Connecticut, the mayor of the city confessed that he had never heard of public history before. To prepare his speech, he googled ‘public history’ and found the NCPH page that compares public history to pornography, which was defined in 1964 by a United States Supreme Court Justice as “I know it when I see it”.7 The mayor confessed to a smiling audience that this definition did not really help him understand the field. If we follow this example, people looking for public history could end up with this Google search result [fig. 2].8 The NCPH’s definition and website, followed by Wikipedia and Weible’s article, were the four first results of my search. Although my location affected the results, they tend to show specific North American views and definitions. What is at stake here is not the validity of the NCPH’s definition, but rather the fact that practitioners, scholars and students (especially outside the US) may have different approaches that should be considered when proposing international definitions of public history. The success and institutionalisation of public history in the United States can be seen as an inspiration but there is a need for alternative international understandings of the field. The NCPH cannot be the unilateral authority in defining international public history. I would strongly argue that defining public history should be an international and collaborative process in which the variety of voices and interpretations contributes to enriching the field. However, the task of defining public history collaboratively and internationally is beset with many challenges.

7 NCPH website, https://ncph.org/what-is-public-history/about-the-field/.

8 As geolocation matters for Google searches, I should clarify that I googled ‘public history’ in Mozilla Firefox on 10 August 2019 in Colorado, USA.

Figure 2 Google Search result for ‘public history’, 10 August 2019

2.2 Problems in Defining Public History

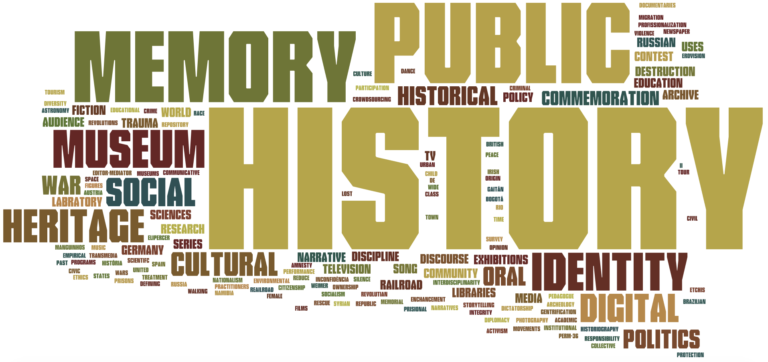

One challenge in defining public history comes from the breadth and variety of practices involved [fig. 3]. This word cloud produced by Anita Lucchesi presents some of the many concepts, practices, tools and issues in public history that arose during the 2018 conference of the International Federation for Public History. This diversity challenges any strict definition of the field. Defining public history creates tensions. In 2007, the NCPH proposed that public history should be defined as “a movement, methodology, and approach that promotes the collaborative study and practice of history; its practitioners embrace a mission to make their special insights accessible and useful to the public” (Corbett, Miller 2007). This prompted strong criticism, with Kathy Corbett and Dick Miller claiming that the statement assigned public historians the role of “missionaries” and denied “lay people a creative role” (Corbett, Miller 2007). The criticisms can partly be attributed to the role of the NCPH in the United States. The organisation was established in the 1970s in response to the variety and heterodoxy of historical practices outside academia. Although it initially contested the idea that academic historians were missionaries bringing knowledge to the public, when it attempted to propose a fixed definition of the field in 2007, the NCPH somehow repeated the same mistake in assigning a ‘mission’ to public history practitioners. The challenge in defining public history is to balance the need to identify and frame the field while offering space for discussion, collaboration and disagreement.

Figure 3 Word Cloud of Keywords of 2018 IFPH proposals, 2018 (Lucchesi 2018)

Moreover, national trends and historiography can make the task of agreeing on an international definition of public history even more problematic. There are debates about the translation of the term itself. For instance, while the English term ‘public history’ is often translated in French (Histoire Publique), Portuguese (Brazil) (História Pública) or Dutch (Publieksgeschiedenis), the Italian Association for Public History (AIPH, Associazione Italiana di Public History) and some programmes in Germany keep the English expression.9 In Italy, one argument for not translating public history was so that Italian practices could be connected to broader international networks.10 As Serge Noiret (president of the AIPH) explains, “individuals are open to the field in Italy and have no problem at all in importing solutions from other countries and readapting them locally”, whereas the term storia pubblica would instead be understood as referring to the controversial uses of the past.11 Although public history is often translated in French, it raises some specific issues, as in French and some other languages the term ‘public’ can indicate close links with the state and its administration, partly because of the long history of the welfare state in Europe. Public history may therefore be understood as either state-sponsored history or even the history of the state administration. Likewise, in post-colonial contexts, using a term that is rooted in British and North American practice can raise tensions.

9 See the website of the German programme at Freie Universität Berlin, http://www.fu-berlin.de/en/studium/studienangebot/master/public_history/index.html, and the programme at the University of Amsterdam, http://www.uva.nl/en/disciplines/history/specialisations/public-history.html. For the programme in Paris, see http://www.u-pec.fr/pratiques/universite/formation/master-histoire-parcours-histoire-publique-644604.kjsp.

10 Interview with Chiara Ottaviano (board member of the AIPH), Ravenna (Italy), 4 June 2017.

11 Interview with Serge Noiret (President of the AIPH), Florence (Italy), 28 July 2017.

There is therefore a definite ambiguity about whether or not we should define public history. I personally do not think it is necessary – or even possible – to provide a strict one-size-fits-all definition of the field that encompasses the multiple international approaches. However, I do think it is necessary to create spaces to discuss what public history can be and how it relates to local, national and thematic practices and theories of history.

3 Public His(tree): An Interconnected and Collaborative System

Several definitions of public history have used metaphors. British historian Ludmilla Jordanova pointed out that “public history must be an umbrella term, one which, furthermore, brings together two concepts ‘public’ and ‘history’ which are particularly slippery and difficult to define” (Jordanova 2000, 149). She presented the field as a way to gather practices under a common name. More recently Italian historian Marcello Ravveduto proposed travelling from land (academia) to the archipelago of public history (Ravveduto 2017, 136). Using this metaphor, Ravveduto posits that public history, much like an archipelago, is made up of small islands (practices) that are distinct but close to one another, connected by the sea. In a similar vein, Jennifer Dickey has recently compared public history to a “big tent”, borrowing the metaphor used for digital humanities (Dickey 2018; Pannapacker 2011).

Using metaphors to define public history has given rise to criticism. Recently, Marko Demantowsky argued for instance that Jordanova’s use of the umbrella metaphor can be persuasive but lacks theoretical grounding and is therefore limited in defining public history. But metaphors can often provide useful insights into the development of the field. They reflect a willingness to see public history as a fragmented field united by a common understanding of the historical process. These definitions depict public history as broadening the traditional historical process, “from land to archipelago”, through specific practices. The focus on practices is also present in the English Wikipedia definition: “Public history is a broad range of activities undertaken by people with some training in the discipline of history who are generally working outside of specialized academic settings […] Because it incorporates a wide range of practices and takes place in many different settings, public history proves resistant to being precisely defined”.12 In all these definitions, the question remains of how practices are connected – or to adopt Ravveduto’s metaphor, which sea connects the archipelago.

12 Wikipedia, “Public history”: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_history.

3.1 From a Trunk to a Tree: Enlarging the Historical Process

Attempting to visualise public history has pros and cons; visualisations are limited in showing the complexity of the historical process. The objective in presenting public history as a tree has no claim to be exhaustive or to present a theory-rooted definition of the field but rather to provoke discussion. Trees have often been used as symbols and metaphors. Many genealogical associations and history departments have used trees to show the connection between past (roots) and present [fig. 4]. Such metaphors have elicited some criticism as well. Proposing a natural element – a tree – as a metaphor of a human-based activity can initially seem surprising. However, the point is to show public history as a system of interconnected parts. The tree represents more than just actors; it shows stages of a process. Others have criticised the metaphor of the tree because it offers a linear and (overly) logical view, from roots to leaves, that does not leave space for ruptures, conflicts or exchanges (Deleuze, Guattari 1987). While the tree image may indeed be problematic for representations of kinship, transmission and ethnic identity, it works well as a metaphor for complex interconnected systems. For instance, Allan Johnson proposes explaining patriarchy and gender systems through the metaphor of a tree (Johnson 2014). He uses the different parts of the tree (roots, trunk, branches and leaves) to explain the articulation of the patriarchal system. Comparing public history to a tree argues that the field is based on interconnected actors – or thousands of hands as Raphael Samuel once described it (Samuel 1994, 15).

Figure 4 History Department logo, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, 2019

Rather than competing and conflicting relations between actors, the tree is built upon a necessary interconnection between roots, trunk, branches and leaves – see the dotted lines on the right of the tree [fig. 5]. The tree is divided into four parts: the roots, the trunk, the branches and the leaves. These parts are different but belong to an overall system; they cannot exist without one another. While history has traditionally been defined as the rigorous and critical interpretation of primary sources (the trunk), public history is broader and includes four parts. The roots represent the creation and preservation of sources; the trunk is the analysis and interpretation of sources; the branches are the communication of those interpretations; and the leaves are the multiple public uses of those interpretations. The more the parts are connected, the richer and more coherent public history becomes. The structure is not linear; uses (leaves) often influence what we deem important to collect and preserve (roots). The Public His(tree) should not be seen as a purely linear process but rather as an interconnected system.

Figure 5 Public History Tree of Knowledge (Cauvin 2019)

Rooted in the Past: Public History as Creation and Preservation of Sources

Public history goes beyond the simple interpretation of primary sources. It helps to create, record, manage and preserve sources. Public history includes archiving, managing collections in museums and other repositories, preserving sites and historical buildings and digitising sources. Creating, managing and preserving sources involves public-oriented objectives that require historical skills – we need to ask if the source is reliable and if it is relevant for our understanding of the past. Without the creation and preservation of primary sources – in the broadest sense, also including buildings, sites, objects, digital-born archives such as emails, and interviews – historical interpretations would not be possible. Roots and trunk are interconnected.

Interpreting Sources, the Trunk of Public History

The trunk is perhaps the most visible part of the tree, and historical interpretation is similarly what has long been considered as the main activity of historians. Although some would set public history against academic history, the two should not be considered as mutually exclusive. In fact, historical research – an expression of academic scholarship – is an important part of public history. Without initial research, public history would have no rigorous methodology for the critical analysis of primary sources and no credentials to deal with the past. Public history has even encouraged particular research methodologies. For instance, with the broadening of primary sources (the roots), historical research is increasingly moving away from only using written sources and is embracing visual, material, built and digital sources.

Communicating History: A System with Many Branches

Historians always have an audience, even if it is a niche of a few experts. But public history encourages historians to communicate to large, often non-academic audiences through multiple media, or branches of the tree. In order to share historical interpretation (trunk) with audiences, practitioners make use of a broad range of communication tools including radio, books, exhibitions, journals, tours, fiction, comics, and more recently digital and new media. A willingness to communicate beyond academic peers and a consideration for new modes of communication and how they affect content are crucial for the development of the field. Communicating with various audiences forces historians to reflect upon their approach, moving away from a jargon and concept-oriented academic style to become user-friendly and engaging.

A Tree with Many Leaves: Uses and Applications of History

Leaves provide trees with glucose through photosynthesis. The fact that history is consumed – and used – in many different ways is not new (De Groot 2008). History is used for many purposes, some of which may include marketing, politics, education, identity, empowerment and simply fun. I would argue that the multiple uses and applications of history must be considered as an important part of public history. One limit of this visualisation is the fact that many leaves connect to each type of communication. Instead of single leaves, the tree could have included areas with multiple uses for each type of communication. However, for the sake of clarity, I decided to design individual leaves. This does not mean that all uses and applications of history are valid and equally significant – there are many debatable political and marketing-related uses of history for instance –, but it emphasises that practitioners cannot ignore how historical research and interpretation are used, consumed and applied by various public groups and individuals.

Trees have many leaves; history has many uses and applications. Public history can therefore sometimes be referred to as applied history. The latter term has been around for much longer – it was proposed by historian Benjamin Shambaugh in 1909 to discuss how history could inform present-day issues and policy (Conard 2013). Applying their skills to present-day issues, historians can work as consultants for governments, agencies, cultural institutions or companies to create and manage archives, to manage historical sites or as expert witnesses in trials (Delafontaine 2015). In North America and the United Kingdom in particular, historians are called on to contribute to public policy, bringing their expertise to the interpretation of past examples (Green 2016).

Visualising public history as an interconnected system also shows that some sites and institutions, such as museums or archives (on the left of the tree), belong to several parts. For instance, by creating collections, producing interpretations and research and also producing narratives – in particular through exhibitions –, as well as offering the possibility of using and consuming the past – for instance in gift shops –, museums demonstrate the richness of the public his(tree). The ways in which people, groups and companies use and consume history have barely been part of history discussions, but they should be part of public history. David Thelen and Roy Rosenzweig show in their study how audiences understand, make sense of, engage with and use history (Thelen, Rosenzweig 2000). Public history practitioners need to consider how their narratives are used and consumed by different audiences and therefore how they impact societies.

3.2 Collaboration, Shared Authority and Public History

While the roots, trunk, branches and leaves of the tree are clearly connected, public history also encourages collaboration within each stage. Public history is not only about working for the public; it is also about working with the public. The public is not a passive audience; it can become an actor in the process. Conceptualised by Michael Frisch to describe the dual authority in oral history – narrator and interviewer –, the notion of shared authority exemplifies how public history invites historians to reconsider the participation of a variety of actors in interpreting the past (Frisch 1990). The crucial challenge is to balance public participation with rigorous and critical methodology at all stages of the process.

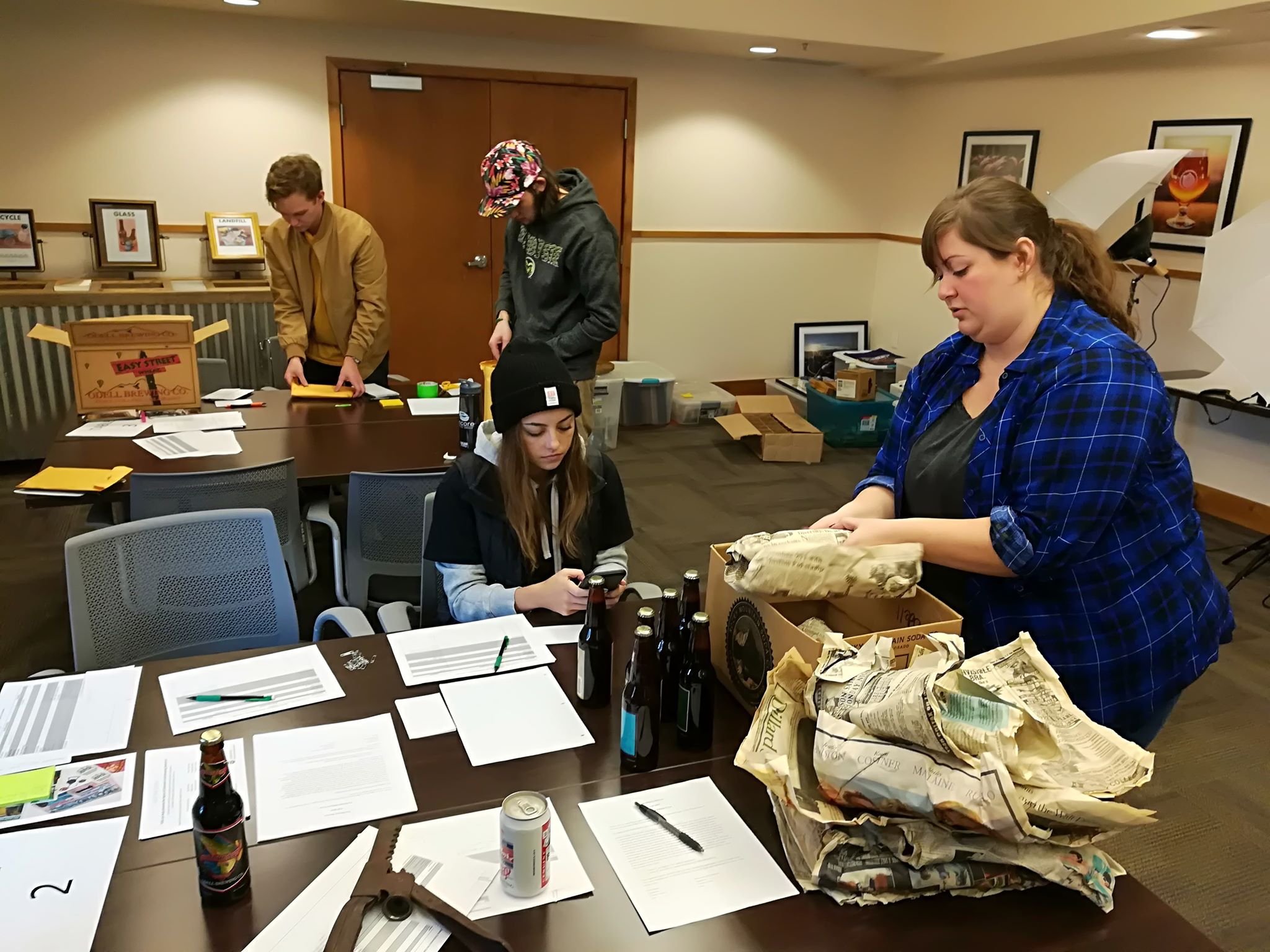

When it comes to the roots of the tree, public participation can help in collecting new sources to document the past. For instance, I have organised several history harvests [fig. 6] in which scholars and students work with local communities to document and collect sources about a given topic. This is why the trunk of the tree is composed of several intertwined channels that represent the participatory and collaborative process. Historical interpretation – the trunk – requires more complex skills and public participation can become more challenging. However, some examples show how members of the public can participate in analysing primary sources and identify sites, actors or materials.13 Public participation in communicating history is also quite widespread. Through the concept of “participatory museums”, Nina Simon has demonstrated how public interaction and public engagement can help visitors to become actors of knowledge production in museums (Simon 2010).

13 See for instance Patrick Peccatte’s project, PhotoNormandie, https://www.flickr.com/people/photosnormandie/.

Figure 6 Public history student collection of artefacts about the history of beer in Colorado, United States, 2019

The collaborative approach of public history is part of a broader process of democratisation of knowledge production that was encouraged by the rise of the Internet. Beginning in the early 2000s, the proliferation of Web 2.0 technologies has allowed users to easily create, edit and share content through crowdsourcing and citizen science projects. With crowdsourcing and user-generated content, cultural institutions and other public history projects have developed collaborative practices in which members of the public can upload and share historical documents, contribute to the process of researching collections and engage with primary sources to interpret the past.14 Such collaborative practices make public history highly engaging as well as subject to criticism since they call for a new definition of the role of historians.

14 See the Children of Lodz Ghetto project at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (Frankle 2013).

3.3 “Not Everyone can Become a Great Artist, But a Great Artist can Come from Anywhere” (Anton Ego, Ratatouille , 2007)

In the past, I have made no secret of my disdain for Chef Gusteau’s famous motto: Anyone can cook. But I realize, only now do I truly understand what he meant. Not everyone can become a great artist, but a great artist can come from anywhere. (Bird 2007)

This quote from the blockbuster movie Ratatouille can be applied to the development of public history. Not everyone can become a great historian, but good public history can come from anywhere. It also means that one does not have to be an academic historian to practise public history. Curators, archivists and other professionals can produce extremely useful collection-based research. Many historical narratives are communicated and shared by non-academic historians. This does not mean that academic historians are not necessary for public history, but they should not be the only actors involved in the process.

The metaphor of the tree posits that historical interpretation (the trunk) is crucial but that it is not an end – or a beginning – in itself. One can be an actor in the system without being a researcher or a professional historian as long as one connects to other stages of the process. For instance, YouTubers who communicate interpretations of the past are actors of public history when they make use of sources (roots) and historical interpretations (trunk) provided by others.15 Through their communication, they also contribute to interpreting the past. Communication is never a neutral process. Just like in a tree, every stage – creating and preserving sources, interpreting sources, communicating history, using and applying history – has a function and is connected to the whole system. Public history practitioners have to be aware of one another and accept collaboration. Developing public history helps to connect archivists, researchers, history communicators, audiovisual producers and their audiences. There can be no communication of history to large audiences without previous research and interpretation, but conversely, research without audience-centred communication can lack public engagement. This is why the development of public history is helping to foster awareness and collaboration between various practitioners, even though some practices have existed for a long time. Public history is the result of a collaboration between many different practitioners, not necessarily professional or academic historians, who are identified by their role, which might be curating objects, writing historical fiction or preserving a historical house, for instance.

15 See for instance NotaBene in France, https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCP46_MXP_WG_auH88FnfS1A.

The question of whether or not public history can be done without professional historians is therefore less relevant than the question of how the different layers relate. Instead of asking whether or not a practitioner is a historian, we should ask which stage of the public history process they are engaging with and how it relates with others. This is why I now tend to refrain from using the term ‘public historian’ – broadly used within the NCPH – and prefer to use the term ‘practitioner’, as not all individuals involved in public history define themselves as historians. I admit that this structure of public history as an interconnected system may sound optimistic – ignoring conflicting practices, interpretations and uses of the past – but it aims to connect the many long-divided practices of history.

Professionally trained historians should not feel disempowered by this approach to public history. On the contrary, the collaborative approach reasserts the need for academic and professional historians, but with different roles. Instead of acting as missionaries bringing knowledge to passive audiences, professional historians could be responsible for sharing methodological skills to study sources. Helping to contextualise and interpret sources is one of the most useful tasks that historians can bring to the field. Historians can participate in the construction of collaborative spaces for interpretation. In 2006, Barbara Franco – President of the American Association for State and Local History – pointed out that the “role of the historian or scholar in civic dialogue must be focused on creating safe places for disagreement rather than on documenting facts or achieving a coherent thesis” (Franco 2006, 3). I agree, but I think that this is not limited to civic dialogue and rather refers to public history at large. Historians can connect the different stages and actors of public history, in other words they can become the sap that connects the roots, the trunk, the branches and the leaves.

4 The Rise of Public History: A Short Historiography

As historian Ian Tyrrell confesses, “scholars tend to see public history as something new” but “historians have long addressed public issues” (Tyrrell 2005, 154). Tyrrell reveals an important misunderstanding. Although the term ‘public history’ was first coined in the US in the 1970s, the practices of ‘doing history in public’ go much further back. Historian Paul Knevel asserts that “ever since the activities of the Italian humanist historians of the fifteenth century, Western historiography had had a public function” and he considers humanists like Bruni and Guicciardini as the first ‘modern’ European public historians, using history to show their fellow burghers important civic duties and the merits of the city-state they were living in (Knevel 2009, 7). The question is not whether or not these humanists were (public) historians; the point is that there has clearly been no lack of publicly-engaged scholars interacting with broad audiences in the past.

Despite these much older examples, the professionalisation of history in the late 19th and early 20th centuries affected the relationship between professional historians and their audiences. History became a scientific and professional discipline for which academic journals became the preferred vehicle of dissemination. Inspired by German historian Leopold von Ranke, professional historians aimed to produce factual historical narratives disconnected from present considerations (Novick 1988, 43). Professional historians addressed more and more specific audiences – their academic peers – and moved away from popular writing styles. This specialisation lay the groundwork for the ‘ivory tower’ that the founders of the public history movement were so keen to dismantle.

The rise of public history as a field in the 1970s was the result of an international re-examination of history-making. As James Gardner and Paula Hamilton rightly explain, “The history of public history as a term and concept is told in the United States as an internal story in which emissaries from the United States introduce it as a practice to the rest of the world. In fact, from the 1970s and 1980s many western countries experienced similar expansion in professionalization of heritage, expansion of history interpretation, and also the oral history movement, the method that provided the most impetus for broader community projects” (Gardner, Hamilton 2017, 4). It is indeed necessary to set the creation of the public history movement in a broader, more international and comparative context.

Some historians developed new publicly-engaged practices in the 1960s and 1970s. In Britain, although the term public history was not used until very recently, new approaches to public participation emerged (Hoock 2010). Historian Raphael Samuel created the History Workshop at Ruskin College (an adult-education institution in Oxford, Britain, strongly rooted in trade unions). His approach came from a “desire to lessen the authority of academic history and thereby further a democratisation of the study and uses of history” (Jensen 2012, 46). In giving voice to under-represented social groups, Samuel was, in terms of participatory process, more radical than the public history movement that emerged in the United States in the 1970s (Schwartz 1993). Comparing historical practices in the US and in Britain, Tyrrell explains that “the British tradition facilitated popular and working class recording of their own historical experiences and involved important contributions to this process by trade unions, workers’ education, and local history groups” (Tyrrell 2005, 157). Less based on radical history and activism, the movement in the US is characterised by its capacity to institutionalise the field through academic training.

Robert Kelley first coined the term public history at the University of California in Santa Barbara in the 1970s. A university professor, environmental historian, consultant and expert witness on matters related to water rights, Kelley wanted to redefine the history profession to include practical applications – and jobs – outside education. He wrote that “public history refers to the employment of historians and historical method outside of academia” (Kelley 1978, 16). According to Wesley G. Johnson, another founding member of the movement, training up public historians was an answer to the isolation of academic historians. Johnson explained that “increasingly the academy, rather than historical society or public arena, became the habitat of the historian, who literally retreated into the proverbial ivory tower” (Johnson 1978, 6). The public history movement in the US set out to create new historians who would break free from the ‘ivory tower’ in which academic historians had been working.

The roots of the movement were also very pragmatic. In a context of global economic depression during the 1970s, universities experienced a major employment crisis. Jobs in higher education fell dramatically. There were too many historians for too few jobs in academia. Public history appeared to be one possible solution to the crisis. The vocational tropism of public history – proposing jobs outside education – matched this context of diversification in higher education.

The unity of the public history movement in the US can partly be explained by the development of university training in the field. The first postgraduate programme in public history opened at the University of California in Santa Barbara in 1976. Two years later, Wesley Johnson launched the first issue of The Public Historian and organised several conferences about public history (Johnson 1999). Held between 1978 and 1980, the conferences contributed to the creation of the National Council on Public History (NCPH) in 1979. The new association, the journal and the creation of university programmes institutionalised public history as a specific field of study.

While the institutionalisation of the field progressed in the US, the concept of public history also resonated in other parts of the world, although public history was often considered as an American model. In 1984, French historian Henry Rousso speculated: “created in the United States, public history is crossing the Atlantic. Is this the future of history?” (Rousso 1984, 105). In Australia, Graeme Davison later argued that public history was mostly informed by the American public history movement (Davison 1998).

Wesley G. Johnson, one of the founding members of the movement in the United States, participated in several international events in which he attempted to bridge various understandings and practices of public history. From 1981 to 1983, he went on several international tours in Europe and Africa during which he listed different programmes that had public history components (Johnson 1984, 91, 95). He met with some historians who were already accustomed to applying history to present-day issues. British historian Anthony Sutcliffe met him in 1980 and immediately saw “the mutual, and understandable, sympathy between public history and urban history in North America” (Sutcliffe 1984, 9; Stave 1983). Sutcliffe explained that he “sensed a potentially constructive common interest between public history and the discipline of economic and social history which, in its distinctive British manifestations, already acknowledged some of public history’s perspectives” (Sutcliffe 1984, 9). But despite this initial convergence, public history practices in Europe did not really materialise until the 2000s.

In 2009, some historians within the NCPH created a working group to internationalise public history (Adamek 2010, 8). While the group was formed within the NCPH, the goal was to go beyond North America. The group evolved into a committee and was formally named the International Federation for Public History (IFPH) in 2010. Although the IFPH initially involved some long-time advocates of public history in the US like Arnita Jones and Jim Gardner, it slowly evolved into a more international network of practitioners. Unlike the process of internationalisation in the 1980s, which mostly attempted to spread a specific approach from the US, the IFPH aims to connect different local and national understandings of the field. The IFPH does not propose a single definition of what public history is or should be. Instead, a recent project created a space for discussion in which practitioners from all over the world can present their sometimes very different views of the field. Since public history is based on collaboration, it makes a great deal of sense to apply this approach to defining the field itself.

5 Public History Under Criticism

This overview of public history should not hide the many debates within – and sometimes harsh criticisms of – the field. Public history has always been a highly contentious field, and these criticisms can help improve our understanding of the issues at stake. While some of the criticisms are based on valid arguments, others demonstrate a reluctance to reconsider the way history is done, performed, taught or communicated. Some of these criticisms and possible responses can be found below. Needless to say, I do not claim that this list is exhaustive. Likewise, each criticism calls for a response developed at length, which would be ill suited to the format of this article. Instead of providing clear-cut, definitive answers, I explore some options to further inform discussions.

5.1 “There is No Need for Public History”

Some scholars have claimed that there is no need for public history. In a now-famous article published in 1981, Ronald Grele, albeit acknowledging the need to engage and communicate with large audiences, explained that “[i]t is probably obvious to point out that historians have always had a public. From its earliest times, the study of history has been a public act” (Grele 1981, 41). He criticised the proponents of public history, claiming that they had forgotten that many historians had long been working in cultural institutions, archives, museums and historical societies. In his view, the creation of a public history movement was partly the result of university-based historians trying to reassert their control over existing local historical practices.

Grele’s assertion indeed raises important issues about how we define public history. Although the term public history was coined in the 1970s, practices of ‘doing history in public’ had been around for much longer, as seen above. In addition to early 20th-century examples of applied history, many other historians had been working in cultural institutions or had been employed by governments and military services. In the United Kingdom, the War Office, the Admiralty and the Committee of Imperial Defence had “their own historical sections before the First World War” (Offer 1984, 28). Historical sections were extended to other departments after WWII (Beck 2006). Other historians worked in companies. In Germany, the Krupp Company developed internal archives as early as 1905 with the help of historians. Likewise, historian William D. Overman became a permanent employee of the US-based Firestone Tire and Rubber Company in 1943 to “establish the first professionally staffed corporate archive in the United States” (Conard 2013, 161). So the public history movement did not invent the wheel; some of its practices already existed and should be included in the historiography of the field. But despite the fact that public history is to some extent based on long-held practices, the movement has served to connect these practices and to enlarge the overall process of history.

Grele’s argument was recently used by Irish historian John Regan to criticise the need for a specific field of public history. According to Regan, “an assumption of public history’s advocates is that the public does not engage with scholarship” and “in the Republic of Ireland, there exists a healthy practice of disseminating historical knowledge from the universities to general audiences”. He cites historians appearing on radio and television or writing for newspapers (Regan 2010, 268). The argument that we do not need a specific field because history is already public resembles the argument of another Irish historian, Gearóid Ó Tuathaigh, who claims that “this notion of an incompatibility between professional and public history (is) fundamentally misconceived” (Ó Tuathaigh 2014). I agree that the strict opposition between the supposedly well-demarcated public history and academic/professional history is problematic. Indeed, what would be the distinction between a public historian and a non-public historian? Going back to the metaphor of a tree, academic scholarship is an integral part of the process if connected to the other stages of public history. John Regan’s vision of public history is, however, limited to communicating history to large audiences. It still represents a top-down approach in which ‘experts’ bring knowledge to passive audiences, with very little public collaboration or participation. What is more, some skills are necessary to practise public history. Designing exhibitions, making audiovisual productions and compiling and managing archives and collections are, for instance, some of the skills that need to be learned to practise public history. We need public history because it helps raise awareness of what it takes to research, interpret, communicate and share historical knowledge.

5.2 “Public History is not History”

“Public history is not history, it is communication”. Another criticism levelled at public history has addressed its alleged lack of historical methodology. I was recently invited to discuss public history training at a public history summer school in Belgrade, Serbia, with students and historians from different parts of Europe.16 I presented the various skills that I want my public history students to acquire during their training. During the discussion with participants, a clear line emerged between public history practitioners – archivists and curators, for instance – and some academics. For the latter, what I had presented was not history but merely communication. They saw the role of historians as primarily carrying out original research and becoming experts in a clearly defined subject area.

16 Applied European Contemporary History website, http://aec-history.uni-jena.de/?timeline_post=2nd-summer-school.

To be fair, in my talk I had not insisted on the historiography and methodology training that my students also receive. However, those criticisms mirror a broader view that public history is too focused on communication and media. I disagree for several reasons. First, just as public history is grounded – the roots and the trunk of the tree – in primary sources and research, public history students receive training in research and historiography. But public history students also learn skills to communicate history to large audiences and to collaborate with various partners and public groups. In the same way that a good researcher does not necessarily make a good teacher, a historian is not necessarily equipped to practise public history. If historians want to work in and with the public, they have to learn skills such as how to curate and design historical exhibitions, write 150-word panels or produce audiovisual projects. History is not communication, but it can learn from communication. Jason Steinhauer thus created a group of history communicators to raise awareness and discussion about communication skills for historians. He explains that “[j]ust as the sciences have prepared a generation of scientists to be Science Communicators, so too is history preparing History Communicators to communicate new historical scholarship to non-experts in today’s complex media environment”.17

17 Jason Steinhauer’s personal website, https://www.jasonsteinhauer.com/history-communicators.

More challenging is the view that public history is not history but rather a sort of memory production. During a seminar on museums and public history held in Quito, Ecuador, one historian argued that public history had more to do with group memories than professional history:18 professional historians write history while communities develop memories. This opposition between history and memory is nothing new. It reflects the rise in memory studies over the past four decades. Some historians, like David Lowenthal, have distinguished between history and memories. In Lowenthal’s comparison, he sets historians who “while realizing that the past can never be retrieved unaltered […] still strive for impartial, checkable accuracy, minimizing bias as inescapable but deplorable” against those – he does not call them historians – who “see bias and error as normal and necessary” (Lowenthal 1997, 32). He claims that there is a multiplicity of memories emanating from groups and individuals, and that it is the task of historians to research those memories as case studies.

18 Universidad Andina Simon Bolivar, “Museos, historia publica, y politcas culturales”, https://www.uasb.edu.ec/contenido?museos-historia-publica-y-politicas-culturales.

In Lowenthal’s view, public history would closely connected to memories because it involves working with groups and communities. For example, I was working with local communities to study the history of the legacy of immigration in Colorado. Working with groups and communities can be challenging as it involves testimonies, individual recollection and emotions such as pride and anger. Peter Novick is critical of a version of public history that he defines as seeking “to legitimize historical work designed for the purposes of particularistic current constituencies”. This definition of public history contrasts with what Novick presents as the “noble dream” of “the universalist ethos of scholarship” (Novick 1988, 471-472, 510). I would argue that, going back to the metaphor of the tree, public history is not simply uncritically remembering the past; as James Gardner stressed in his critique of radical trust, (public) history is not mere opinion (Gardner 2010). Communication and uses of the past – branches and leaves – are connected to primary sources and their critical interpretation. Historians help public groups and communities develop skills to use, interpret, contextualise and compare evidence of the past. The role of trained historians is more than merely sharing their knowledge of the past; it involves sharing their skills to interpret and understand the past.

According to the criticism outlined above, working with multiple partners and public groups could lead to the fragmentation of the narratives of the past, resulting in plural memories rather than a single history. However, simply contrasting a plurality of memories with a singular history is a naive presentation of the field that ignores the many ‘history wars’ and debates when interpreting the past. Besides, multiple perspectives do not necessarily mean a lack of critical rigour in developing views of the past. For instance, the Their Past Your Future exhibition presented the Second World War from the perspective of UK veterans through testimonies (Sayer 2019, 14). But the exhibition, as a public history project, was not merely a collection of uncritical memories. Testimonies were coupled with other primary sources, footage and contextualisation. The project had the benefit of showing specific interpretations of the war while connecting them to a broader context and historical narratives. This balance between several interpretations of the past and the broader context is vital for public history as it shows how events may have a variety of valid interpretations. Sarah Lloyd and Julie Moore have proposed the concept of “sedimented histories” which can “hold different accounts of the past alongside one another, accommodating both the histories that people choose to live by and the histories that everyone lives with” (Lloyd, Moore 2015).

Public history can contribute to reconciling history and memory. Its participatory practices provide a space for individual and collective memories in the production of historical narratives. In 1996, historian David Glassberg led a discussion on the links between public history and memory (Glassberg 1996). The discussion explored how individual and collective memories can be part of public history projects. For instance, it is common in historical preservation for members of local communities to take part in discussions about what should be preserved, why and how. Public memories of sites help us discover new layers of interpretation and strengthen the authenticity of narratives. The production of public understanding of the past is more complex than a simple confrontation between history and memory. In his answer to Glassberg’s article, Robert Archibald pointed out that “the new memory research is especially important because it is audience-focused and recognizes that examining how humans receive information and construct memory is critical to our work” (Archibald 1997, 64). Different public uses and interpretations of the past are crucial to understanding how audiences make ‘sense of history’, or as Glassberg put it, as evidence of the intersection of the intimate and the historical (Glassberg 2001, 6).

5.3 Public History, Consultants and Clients

Because of its multiple connections with partners, public history has also been criticised for being present-centred. Regan argues that “Public histories popularize the past, but they are conditioned by the needs of the present. They may want to win votes for the government or loyalty for a cause, or just pay their way as commercial ventures. Public histories pander to the expectations of mass audiences, whereas historical research is more interested in the past for its own sake” (Regan 2012). Although this opposition between multiple public histories and a singular and objective historical research is highly debatable, it raises important questions about ethical issues.

Criticising public history for being market-oriented is not new nor specific to the field. There have been debates on how heritage management is influenced by marketing and commercialisation. Some scholars have denounced the packaging of the past through heritage management (Baillie, Chatzoglou, Taha 2010). In 1996, Michael Wallace criticised the ‘disneyfied’ history proposed at some museums and historical sites in the US (Wallace 1996). He claimed that some heritage projects proposed ‘edutainment’, a mix of education and entertainment, to attract more audiences, to the detriment of historical accuracy. The rise of entertainment as a policy driver for historical and heritage sites has been deplored by some scholars because of its commercialising of history. As Faye Sayer points out, “public historians have been accused of using the media and its techniques to sensationalize and romanticize the past in order to create an unrealistic, yet publicly appealing, version of history” (Sayer 2019, 15). The close links between public history and historical sites, museums and other cultural institutions – sometimes for-profit companies – make those criticisms important for ethical discussions.

Ethics and ethical practices are crucial for public history, especially when partners and clients have multiple non-educational objectives, some of which may be profit-based. Discussions on ethics are also important for historians who work as individual consultants isolated from large structures such as universities, cultural institutions, national parks or other public agencies. From the outset, historical consulting – for instance the US-based firm Historical Research Associates – has been closely associated with the NCPH.19 In the early 1980s, Johnson noticed reluctance and criticism regarding the application of history during his tours in Europe. He observed that German students and scholars were sceptical about “historians working with business corporations” and openly hostile “to the idea of historians working with federal government agencies” (Johnson 1984, 90). Similarly, Novick wondered whether consultants, under the pressure of their clients, would focus merely on the historical records that “support the case they were making, and [would do] their best to sweep under the rug or trivialize discrepant findings” (Novick 1988, 514). Criticisms focused on the fact that historical narratives would become a product and, like any product, would be sold for marketing or political purposes.

19 The NCPH provides specific resources for consultants: https://ncph.org/publications-resources/for-practitioners-and-consultants/.

However, pressure and interference are not limited to consultants. Fuelled by the recent upsurge in populism and political uses of the past, every historian – including those working in universities – can be affected by interference and pressure (Etges, Zumdorf, Machcewicz 2018). The founding members of the public history movement in the US did not ignore ethical questions. Every article of the first issue of The Public Historian mentioned ethical issues in public history.20 The NCPH set up an Ethics Committee in the early 1980s that led to the development of the first NCPH Ethical Guidelines in 1985 (Karamanski 1986). Theodore Karamanski led a round table on Ethics and Public History and later published a collection of essays entitled Ethics and Public History in 1990 (Karamanski 1990). In 2007, the NCPH updated its Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct, highlighting public historians’ responsibility towards the public, their clients and employers, and towards the profession and colleagues.21

20 The Public Historian, 1(1), 1978.

While those resources are available to all historians, it is still essential to engage in discussions about the role of historians and the uses of history. Ethics are so crucial that they must be discussed and practised in public history training. A recent proposal for an online Master of Public History at the State University of New York proposes an entire course on Ethics and Public History, an initiative that should also be introduced in any public history training programme.22 But ethical issues remain challenging for two reasons. First, the broad range of public history practices, formats and partnerships makes it difficult to provide one single code of ethics for the whole field. Ideally, codes of ethics from other related fields such as museums and archives should also be consulted.23 Working for/with museums requires a different set of ethics from historical preservation or audiovisual production. Second, ethical practices may vary from one country to the other depending on laws and regulations. It is important for the international public history movement to provide help, resources, guidelines and institutional support for historians working outside academia all around the world.

22 Although the Master is not available yet, more information can be found on the website for the certificate in public history: https://www.esc.edu/graduate-studies/advanced-certificates/certificate-public-history/.

23 For the US, see for instance the American Alliances for Museums’ Code of Ethics, https://www.aam-us.org/programs/ethics-standards-and-professional-practices/code-of-ethics-for-museums/, and the Society of American Archivists’ Core Values Statement and Code of Ethics, https://www2.archivists.org/statements/saa-core-values-statement-and-code-of-ethics.

5.4 “Public History is a Set of Blind Practices”

Some historians have asked for more theoretical understanding of public history. During an international workshop at the University of Wroclaw, Poland, in March 2018, three experts in the field – David Dean, Jerome de Groot and Cord Arendes – underlined the need for more theorisation of the terms ‘public’ and ‘history’ and the links between the two.24 De Groot points out in a forthcoming article that “public history historiography has been driven by pedagogical models that privilege skills, ethics, and a ‘professional-based practice approach’”. He goes on to say that “it remains the case that public history lacks a model for critical engagement with corporations, or a flexible way of ‘reading’ their contribution to historical awareness”.25 As early as 1984, while comparing practices in France and in the US, Henry Rousso stressed that “pragmatism is not a French quality (or impairment)” – implying that historians in the US were – perhaps too eagerly – driven by public practices (Rousso 1984, 114). In his view, before any application of public history, French historians would need to engage in major theoretical debates.

24 Applied European Contemporary History, “The Public in Public and Applied History”, University of Wroclaw, March 2019, http://aec-history.uni-jena.de/.

25 Forthcoming article in The Public Historian. I am grateful to Jerome de Groot for giving me access to his article.

At first glance, a lack of theorisation is a fair criticism. Many panels of public history conferences, at least in the US, are about ‘how to’ practice in the field.26 Public history teaching also focuses a great deal on skills and practices. The NCPH confirmed this trend by recently undertaking a survey of public history employers to list the main skills that public history students need to find jobs (Scarpino, Vivian 2017). However, this lack of theory is only partially true. Many university training programmes on public history propose introductory courses that discuss theories and approaches to the field. Public history courses provide excellent opportunities to develop self-reflective practices among historians and history students. I would also argue that the opposite, namely a lack of practices, can paradoxically challenge the development of the field. Many academic historians are not used to practising history outside academic circles, and one initial reflex may be to study – and not to practice – public history, focusing merely on the theories of the field without engaging or collaborating with audiences. Public history should not become a new form of memory studies in which historians merely study representations of the past.

26 See the NCPH website for the programmes of past conferences: https://ncph.org/.

The need to balance theories and practices can help when discussing specific challenges in the field. We should develop and propose new theories to accompany public collaboration, co-production and shared authority. Although some books have been published recently, more discussion is needed on how to balance public participation and rigorous critical methodology to interpret the past (Adair, Filene, Koloski 2011). Working with several European partners, I have been developing a collaborative research project to find new approaches and theories on how to practise public history.27 We should not see the ‘public’ as a singular notion, we should instead consider the many ‘publics’ – the variety of groups, actors and partners – that take part in public history. While Michel-Rolph Trouillot proposed an excellent interpretation of the power relations and agencies at stake in the creation and preservation of archives, other themes must also be debated (Trouillot 1997). In 2002, Jill Liddington proposed that public history should be connected with theoretical discussions on the public sphere, popularised in 1962 by Jürgen Habermas (Liddington 2002, 89). Various questions may arise: How do we define and identify these audiences and participants? Are practitioners collaborating with all or only a few public groups? Should Holocaust deniers and racist or fascist groups be part of the collaboration? If not, who decides, and on what basis, with whom to collaborate? Are we only collaborating with groups with whom we share values? If so, we need to discuss our approaches to and definitions of audiences and participants and their role in public history.

27 Public History as the New Citizen Science of the Past, Luxembourg Centre for Contemporary and Digital History, https://www.c2dh.uni.lu/projects/public-history-new-citizen-science-past-phacs

More theory also means some self-critical assessment. By comparing practices and approaches, international public history can encourage self-reflection. For instance, public history tends to focus on contemporary – especially 20th-century – history. Stefanie Samida, an archaeologist and media studies scholar, rightly argues that limiting public history to a certain era may be one of its weaknesses (Samida 2011). However, this is not true for every national context. In Italy, the AIPH includes many examples of projects and actors connected with antiquity and public archaeology.28

28 See also the conference Medievalism, Public History, and Academia: The Re-creation of Early Medieval Europe, c. 400-1000 (Malmö University, 26-28 September 2018), https://exarc.net/history/call-papers-medievalism-public-history-and-academia.

It would be presumptuous to make hasty conclusions about a field – public history – that is so recent and diverse. If anything, the internationalisation of public history has demonstrated the existence of various approaches and understandings of the field. The multiple approaches pave the way for rich and complex debates about broader uses, practices and theories of history. Some of those history practices were in existence long before the term public history was coined, but the conception of public history as a field offers several advantages. Comparing public history to a tree helps to present the field as a system in which all parts – roots, trunk, branches and leaves – are connected. Each part, and every player, of public history benefits from the whole system. The fact that primary sources and critical methodology are at the basis of public history is particularly important in a context of fake news, mistrust and disinformation, in which historians can bring expertise. Public history calls for a general reappraisal of trained historians’ role. Developing public history will involve trained historians sharing authority with other actors and questioning how history is used and consumed by individuals, communities, groups, institutions, agencies and governments. Far from denying the role of historians, public history provides them with new opportunities to engage and interact with the public. Rather than merely giving lectures and providing truths about the past, historians can work on building collaborative spaces and projects in which all actors can learn, practise and share skills to collect, analyse, interpret and communicate history. If successful, the tree of public history has the potential to contribute to the democratisation of knowledge production while maintaining a critical and methodological understanding of the past.

Bibliography

Adair, B.; Filene, B.; Koloski, L. (eds) (2011). Letting Go? Sharing Historical Authority in a User-Generated World. New York: Routledge.

Adamek, A. (2010). “International Task Force”. Public History News, 3(1), December, 8-9.

Archibald, R.R. (1997). “Memory and the Process of Public History”. The Public Historian, 19(2), 61-4. https://doi.org/10.2307/3379144.

Baillie, B.; Chatzoglou, A.; Taha, S. (2010). “Packaging the Past. The Commodification of Heritage”. Heritage Management, 3(1), 51-71. https://doi.org/10.1179/hma.2010.3.1.51.

Beck, P. (2006). “Public History: Civic Engagement and the Historical Profession”. Unpublished paper.

Bird, B. et al. (2007). Ratatouille. Burbank (CA): Walt Disney Home Entertainment.

Cauvin, T. (2016). Public History: A Textbook of Practice. New York; London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315718255.

Cauvin, T. (2018). “The Rise of Public History: An International Perspective”. Historia Critica, 68, 3-26. https://doi.org/10.7440/histcrit68.2018.01.

Conard, R. (2013). Benjamin Shambaugh and the Intellectual Foundations of Public History. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt20q2006 .

Corbett, K.; Miller, D. (2007). “What is Public History?”. H-Net Discussion Networks, May. https://lists.h-net.org/cgi-bin/logbrowse.pl?trx=vx&list=H-Public&month=0705&week=c&msg=HAUuHywQGvciGXBxeGKPgw&user=&pw=.

Davison, G. (1998). “Public History”. Davidson, G.; Hirst, J.; MacIntyre, S. (eds), Oxford Companion to Australian History. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 532-5.

De Groot, J. (2008). Consuming History: Historians and Heritage in Contemporary Popular Culture. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203889008-5.

Delafontaine, R. (2015). Historians ad Expert Judicial Witnesses in Tobacco Litigation. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14292-0.

Deleuze, G.; Guattari, F. (1987). A Thousand Plateaus. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Demantowsky, M. (ed.) (2018). Public History and School. International Perspectives. Berlin: De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110466133.

Dichtl John; Townsend, R.B. (2009). “A Picture of Public History: Preliminary Results from the 2008 Survey of Public History Professionals”. Public History News, 29(4), September. https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/september-2009/a-picture-of-public-history.

Dickey, J. (2018). “Public History and The Big Tent Theory”. The Public Historian, 40(4), November, 37-41. https://doi.org/10.1525/tph.2018.40.4.37.

Etges, A.; Zumdorf, I.; Machcewicz, P. (2018). “History and Politics and the Politics of History: Poland and its Museums of Contemporary History”. International Public History, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.1515/iph-2018-0006.

Franco, B. (2006). “Public History and Civic Dialogue”. OAH Newsletter, 34(2), May, 3-6.

Frankle, E. (2013). “Making History with the Masses: Citizen History and Radical Trust in Museums”. MITH, 4 April. https://mith.umd.edu/dialogues/making-history-with-the-masses-citizen-history-and-radical-trust-in-museums/.

Frisch, M. (1990). A Shared Authority: Essays on the Craft and Meaning of Oral and Public History. Albany: SUNY Press.

Gardner, J.B. (2010). “Trust, Risk and Public History: a View from the United States”. Public History Review, 17, 52-61. https://doi.org/10.5130/phrj.v17i0.1852.

Gardner, J.; Hamilton, P. (eds) (2017). Oxford Handbook of Public History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199766024.001.0001 .

Glassberg, D. (1996). “Public History and the Study of Memory”. The Public Historian, 18(2), 7-23. https://doi.org/10.2307/3377910.

Glassberg, D. (2001). A Sense of History: The Place of the Past in American Life. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Green, A. (2016). History, Policy and Public Purpose. London: Palgrave Pivot. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-52086-9.

Grele, R. (1981). “Whose Public? Whose History? What is the Goal of a Public Historian?”. The Public Historian, 3(1), Winter, 40-8. https://doi.org/10.2307/3377160.

Hoock, H. (2010). “Introduction”. The Public Historian, 32(3), 7-24. https://doi.org/10.1525/tph.2010.32.3.7.

Jensen, B.E. (2012). “Usable Pasts: Comparing Approaches to Popular and Public History”. Kean, H.; Ashton. P. (eds), Public History and Heritage Today. People and Their Pasts. London; New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 42-56. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230234468_3.

Johnson, A. (2014). The Gender Knot: Unraveling Our Patriarchal Legacy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Johnson, W.G. (1978). “Editor’s Preface”. The Public Historian, 1(1), 4-10. https://doi.org/10.2307/3377660.

Johnson, W.G. (1984). “An American Impression of Public History in Europe”. The Public Historian, 6(4), Fall, 86-97. https://doi.org/10.2307/3377384.

Johnson, W.G. (1999). “The Origins of the Public Historian and the National Council on Public History”. The Public Historian, 21(3), Summer, 168-9. https://doi.org/10.2307/3378969.

Jordanova, L. (2000). History in Practice. London: Arnold.

Karamanski, T. (1986). “Ethics and Public History: An Introduction”. The Public Historian, 8(1), 5-12. https://doi.org/10.2307/3377069.

Karamanski, T. (1990). Ethics and Public History: An Anthology. Malabar: Krieger Pub Co.

Kean, H; Ashton, P. (eds) (2012). Public History and Heritage Today. People and Their Pasts. London; New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kelley, R. (1978). “Public History: Its Origins, Nature, and Prospects”. The Public Historian, 1, Fall, 16-28. https://doi.org/10.2307/3377666.

Knevel, P. (2009). “Public History. The European Reception of an American Idea?”. Levend Erfgoed. Vakblad voor public folklore & public history, 6(2), 4-8.

Liddington, J. (2002). “What is Public History? Publics and Their Pasts, Meanings and Practices”. Oral History, 30(1), 83-93.

Lloyd, S.; Moore, J. (2015). “Sedimented Histories: Connections, Collaborations and Co-Production in Regional History”. History Workshop Journal, 80(1), 234-48. https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/dbv017.

Lowenthal, D. (1997). “History and Memory”. The Public Historian, 19(2), Spring, 30-9. https://doi.org/10.2307/3379138.

Lucchesi, A. (2018). Public History: Brazil Goes International! IFPH website. https://ifph.hypotheses.org/1942.

Lucke, M.; Zumdorf, I. (2018). Einfuhrung in Die Public History. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht.

Mauad, A.M.; De Almedia, J.R.; Santhiago, R. (eds) (2016). História pública no Brasil: Sentidos e itinerários. São Paulo: Letra e Voz.

Novick, P. (1988). That Noble Dream: The “Objectivity Question” and the American Historical Profession. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Offer, A. (1984). “Using the Past in Britain: Retrospect and Prospect”. The Public Historian, 6(4), 17-36. https://doi.org/10.2307/3377380.

Ó Tuathaigh, G. (2014). “Commemoration, Public History and the Professional Historian: An Irish Perspective”. Estudios Irlandeses, ix. https://doi.org/10.24162/ei2014-4028.

Pannapacker, W. (2011). “‘Big Tent Digital Humanities,’ a View From the Edge”. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 31 July. https://www.chronicle.com/article/Big-Tent-Digital-Humanities/128434.

Ravveduto, M. (2017). “Il viaggio della storia: dalla terra ferma all’arcipelago”. Bertella Farnetti, P.; Bertuccelli, L.; Botti, A. (eds), Public History. Discussioni e pratiche. Milan: Mimesis, 131-46.

Regan, J. (2010). “Irish Public Histories as an Historiographical Problem”. Irish Historical Studies, xxxvii, 265-92. https://doi.org/10.1017/s002112140000225x.

Regan, J. (2012). “Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde: The Two Histories”. History Ireland, 20(1). https://www.historyireland.com/20th-century-contemporary-history/dr-jekyll-and-mr-hyde-the-two-histories-2/.

Rousso, H. (1984). “L’histoire appliquée ou les historiens thaumaturges”. Vingtième Siècle, 1, 105-22. https://doi.org/10.2307/3770138.

Samida, S. (2011). Inszenierte Wissenschaft: Zur Popularisierung von Wissen im 19. Jahrhundert. Bielefeld.

Samuel, R. (1994). Theatres of Memory: Past and Present in Contemporary Culture, vol. 1. London: Verso.

Sayer, F. (2019). Public History: a Practical Guide. 2nd ed. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Scarpino, P.; Vivian, D. (2017). What Do Public History Employers Want?. https://ncph.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/What-do-Public-History-Employers-Want-A-Report-of-the-Joint-Task-Force-on-Public-History-Education-and-Employment.pdf.

Schwartz, B. (1993). “History on the Move: Reflections on History Workshop”. Radical History Review, 57, 203-20. https://doi.org/10.1215/01636545-1993-57-203.

Simon, N. (2010). The Participatory Museum. Museum 2.0. http://www.participatorymuseum.org

Stave, B.M. (1983). “A Conversation with Joel A. Tarr: Urban History and Policy”. Journal of Urban History, 9, 195-232. https://doi.org/10.1177/009614428300900203.

Sutcliffe, A. (1984). “Gleams and Echoes of Public History in Western Europe: Before and after the Rotterdam Conference”. The Public Historian, 6(4), 7-16. https://doi.org/10.2307/3377379.

Thelen, D.; Rosenzweig, R. (2000). The Presence of the Past: Popular Uses of History in American Life. New York: Columbia University Press.

Trouillot, M.-R. (1997). Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston: Beacon Press.

Tyrrell, I. (2005). Historians in Public: The Practice of American History, 1890-1970. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Wallace, M. (1996). Mickey Mouse History and Other Essays on American Memory. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Weible, R. (2008). “Defining Public History: Is it Possible? Is it Necessary?”. Perspectives on History, 1 March. https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/march-2008/defining-public-history-is-it-possible-is-it-necessary.

Weyeneth, R. (2013). “A Perfect Storm”. History@work, 6 September. https://ncph.org/history-at-work/a-perfect-storm-part-1/#more-3666.