Digital Public History Inside and Outside the Box

Abstract The relationship between history and information technology is long and troubled. Many projects have opened and closed, many pioneering initiatives have achieved success and attention, but often they have not ‘taught’ or left a fruitful legacy. These experiments, studies and conferences have built a rich basis for the relationship between the disciplines, but the difficult connection needs to be further explored. Although no digital history research centres exist in Italy nowadays, it is possible to look at several Italian projects in order to discuss the strange position of the digital issue within public history conferences, the place of history in the large digital humanities environment and finally the definition itself of digital history.

Keywords Digital history. Digital humanities. Public history. History. Computer science.

1 Introduction

There is a long-standing relationship between historians and information technology. Historians were among the first humanists to welcome the emergence of new analysis tools developed by ITC. Several pioneering projects, studies and conferences have shaped a difficult and often unsatisfactory relationship between the two areas.1 Instead of retracing this long and intricate relationship, we will focus on recent Italian meetings and current Italian digital humanities projects. The aim of this essay will be to present and extrapolate the role of digital analysis in the historical Italian researchers’ work. 2

1 Gil 2015, 161-78; 2019, 177-81. From this point of view, the autobiography of Manfred Thaller is extremely interesting (Thaller 2017, 7-109).

2 All translations, if not otherwise stated, are made by the Author.

The meetings taken into consideration are the 2018-2019 national conferences of the Italian Association of Public History (AIPH)3 and the 2018-2020 national conferences of the Italian Association for Digital Humanities and Culture (AIUCD)4 on the basis of the respective abstract books. The selected abstracts from the 2018 first conference of the Italian Association of Medieval Historians (SISMED)5 were also taken into account. SISMED is the only group among the national Coordination of Historical Societies6 that chose this form of communication for their recurring meeting. The evolution of historical research can be inferred from the proceedings of these institutional meetings, which were organised by national historical associations. The accepted abstracts are concise, structured descriptions with keywords, but not yet filtered by the long process of peer review of the scholarly journals. The collected data has been compared with the Italian digital humanities projects highlighted on the AIUCD website7 and with the essays of a recent book dedicated to Digital History (Paci 2019).

6 http://www.sissco.it/articoli/componenti-del-coordinamento-delle-societa-storiche/. The coordination includes the Central Council for Historical Studies, the Italian Association of Public History (AIPH), the University Council for the History of Christianity and Churches (CUSCC), the University Council for Greek and Roman History (CUSGR), the Society of Italian Economic Historians (SISE), the Italian Society of Historians Women (SIS), the Italian Society for the History of the Modern Age (SISEM), the Italian International History Societies (SISI), the Italian Association of Medieval Historians (SISMED), the Italian Society for the Study of Contemporary History (SISSCO).

2 Digital Humanities in AIPH and in SISMED

Although public history is a field of historical research that has long been widespread in several nations, it is only recently that this ‘discipline’ has been galvanised in Italy with the creation – unprecedented in Europe – of the AIPH and the organisation of three highly attended national conferences.8 This subject is peculiar and interesting for our purposes, because it is highly diachronic and transdisciplinary, given that it has no chronological limits and collects initiatives promoted by very different professional actors, united by the red thread of history: historians, documentary filmmakers, journalists, archivists, museologists, librarians, photographers, cultural operators, re-enactors etc. In short, in the public history field an extremely wide concept of history is used by a large range of people who ‘make history’, in a way that sometimes looks too dispersive, but by bucking the heavy disciplinary specialisation of the academic world.9 However, concerning our analysis – the importance of digital history for the production of knowledge by historians –, the AIPH books offer different qualitative and quantitative data in comparison to what is found in a traditional miscellaneous volume of ancient, medieval, modernist or contemporary historians. In fact, our society values the promotion of participatory projects and the involvement of the public. This makes digital tools and methods often indispensable and relevant for the public historians, compared to a more traditional research practice in the academic environment. Unfortunately, a comparative analysis of the transversal historiographical production of the academic Italian world is greatly hampered by the variety and the quantity of the sector’s scholarly journals. As mentioned, there has been only one book of abstracts published by a traditional historians’ national association. The analysis of this unique piece, the collection of SISMED documents composed just after the first national conference (SISMED 2019),10 provides the following data: out of 140 interventions, distributed in 48 panels, a significant use of typical digital humanities tools and methods has been found only in 2 panels (4.2%) and 6 papers (4.2%); in no case was the digital issue a central topic, not even in order to address methodical issues.

8 Ravenna 2017, Pisa 2018, Santa Maria Capua a Vetere-Caserta 2019. The fourth (Venezia-Mestre 2020) was cancelled because of the pandemic COVID-19. On the Public History in Italy and in the international framework, see Noiret 2009, 275-327; Noiret 2011, 10-35; Cauvin 2018, 3-26.

9 The Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research (MIUR) provides up to 77 different sectors for the area 10 Sciences of antiquity and philological-literary and historical-artistic sciences, even if with exquisitely literary and linguistic disciplines; the area 11 Historical, philosophical, pedagogical and psychological sciences has 34 sectors: https://www.miur.it/UserFiles/116.htm.

10 SISMED 2019. This book consists of a simple juxtaposition of the original texts by the editors, without any editorial homogenization; therefore, there are considerable differences in the length and in the structure of the texts, which limits the possibility of their comparative analysis.

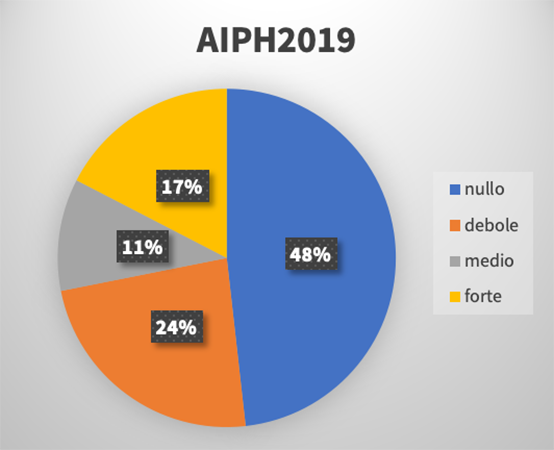

Let us now look at the data obtained from AIPH 2018 and AIPH 2019 (Salvatori, Privitera 2018; Santarelli 2019). A first analysis concerned the importance of the ‘digital’ in the papers according to four levels: unsatisfactory, weak, medium and strong. See figure 1 for the results (translation: nullo = zero or unsatisfactory, debole = weak, medio = medium and forte = strong) [fig. 1].

Figure 1 Comparison of the ‘weight’ of the ‘digital’ in papers analysed during AIPH 2019

The number of proposals without connection to the digital world and its tools has strongly decreased and the attention to the new technologies has deepened at the same time; the second remarkable feature is that the ‘medium’ and ‘strong’ values largely exceed those expressed by the SISMED’s book for both years.

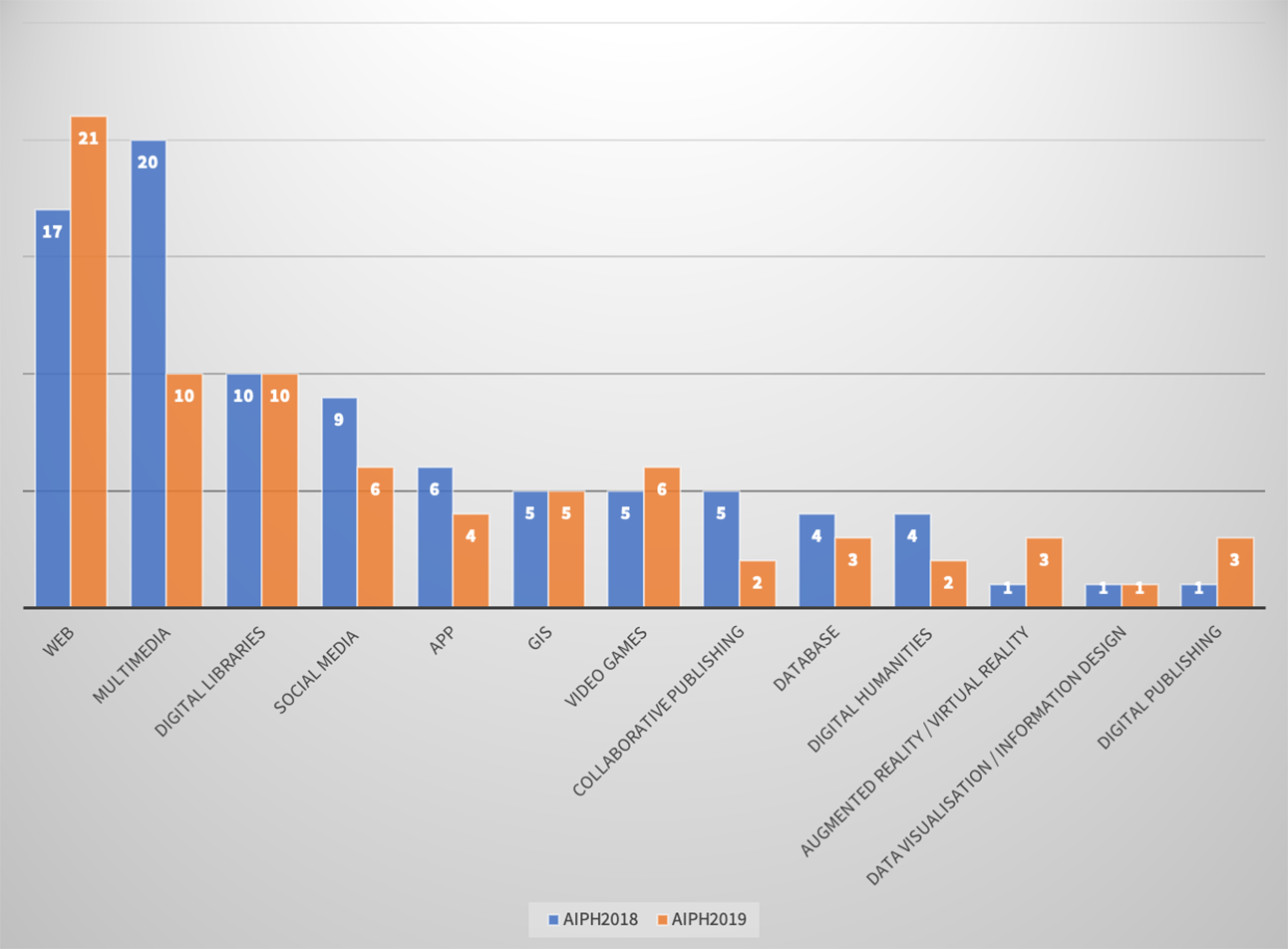

After carefully analysing which tools and methods of digital humanities are being privileged in the domain of public history, though considering only presentations for the medium employed and the strong proposal, the results of this inquiry are shown in figure 2 [fig. 2].

Figure 2 Tools and methods of digital humanities in Italian public history congresses

The most interesting areas of the digital world are the web and social media. Public History activities take place mainly in the ‘real’ world and in ‘material’ projects, but this field undoubtedly received a consistent boost from the web, finding new and extremely effective tools for interacting with its own various audiences. I do not refer to a simple presence on the web – as a showcase –, nor to a new digital shape given to the traditional dissemination: the use of the web and social media in a good public history project needs a well balanced and complementary use of different media organised around the web interface; this interface turns into a complex construction, with qualified maintenance duties, when it becomes a gateway for collaborative projects for digital source collections (by crowdsourcing). On the web the public historian knows not only how to organise contents and manage collections but has to turn him/herself into a ‘manager of participation’, skilled both with a good basic competence on different digital tools, and with a deep understanding of communicative methods and languages.

This situation clearly emerged in a study I conducted with the students of the master’s degree program in Digital Humanities in Pisa from 2017-2018. In collaboration with AIPH, in September 2017 I promoted a spontaneous collection of best Public History practices in order to better define the extremely manifold panorama of practices that emerged from the 1st national conference in Ravenna (June 2017) and to propose guidelines for the promotion and the implementation of Public History initiatives.11 The projects were examined and discussed within the Digital Public History course I held, through the development and the use of an evaluation grid based on authorship, fairness, transparency, methodological validity, participation and role of the public historian. One of the aspects that the students have most evaluated and discussed was the presence of the digital in Public History practices. The other aspect evaluated was the possibility to distinguish Digital History and Digital Public History. About the first point, the projects were really heterogeneous, starting from a superficial or immature presence on the web as meta-medium to an aware and highly specialised use of it. The latter level concerned activities that combined the creation of the project site – in order to publish historical sources with metadata – with a differentiated use of the social networks to collect the sources with crowdsourcing practices. Equally another aspect that was highly appreciated was the transition from the video lesson or interview (a digital version of the classic conference) to different formats with video-dialogues shared on social media open to comments and interactions.

11 The practices were collected by a call spread through the AIPH website and on the main social networks (Facebook and Twitter). The collection was made through a Google form that asked compilers to provide, besides the description of the project, details on the sources used, the relationship with the public, the main medium, the nature of the promoters. See the report in Salvatori 2018.

In short, the initiatives that made a qualitative leap were those that had consciously used digital humanities tools and methods to implement collaborative practices for history, crowdsourcing initiatives, opportunities for dialogue between private memories and institutional archives, up to virtual reality and multisensory paths. In this sense, the digital public historian seems to acquire the role of the “designer of the historical knowledge […] who apply investigation, analysis, imagination and interpretation as ‘techniques’ to create meaningful media environments suitable for the communities he/she wants to involve”.12

12 Salvatori 2018, see the contribution of Stefano Capezzuto.

Going back to figure 2, the second most popular topic, after the methods and tools related to the web, concerns the techniques and the methodologies related to the construction of Digital Libraries (i.e. the organised collection of digital information) (Tammaro 2005). Other tools seem to have a minor role, although the importance of apps, GIS (geographic information system), and video games must be recognised. Video games, however, are not usually built by the public historian, but only analysed for their possible use in Public History practices.13

13 With the important exception of the gamification project by Fabio Viola: https://www.tuomuseo.it/.

3 History in the AIUCD Digital Humanities

The AIUCD was established in March 2011. Since its first conference, it collected and published the proceedings of its national initiatives, even if in different formats; the recent update of the site, more or less in correspondence with the birth of the official journal Umanistica Digitale,14 has allowed for a better organisation of these materials and therefore has also facilitated the analysis.15 For the years 2018-2020 there are two books of abstract and a book of proceedings, whose structure is really comparable.16

15 On Umanistica Digitale in the BoA page there are the Books of Abstract of the 2016-2019 meetings and the proceedings of 2013 and 2020 (https://umanisticadigitale.unibo.it/pages/view/boa); in the site also the materials of the 2012, 2014 e 2015 meetings are linked (http://www.aiucd.it/convegno-annuale/).

16 The main difference is that for AIUCD2020 authors were asked to submit an extended essay after the first selection. These are the books: Spampinato 2018; Allegrezza 2019; Marras et al. 2020.

Given that all the abstracts are related to the complex galaxy of the digital humanities, my research obviously concerned the presence and role of History as a discipline. Once I identified the historical research, I focused on the tools and methods used to carry out the studies. The first problem in labelling the papers was to define the ‘historical’ projects. I distinguished them from those dealing with other subjects. Such distinction was extremely difficult to make, although I founded it on consistent and solid motivations: on the one hand, digital humanities are, by nature, interdisciplinary and therefore usually create extremely hybrid communities of practice; on the other hand, working in the field of human sciences, digital humanists always exhibit a relationship with history, whether they take care of the edition of a text, build digital libraries of cultural heritage, model an epigraph in 3D, or focus on the analysis of a phenomenon using Social Network Analysis. However, there is an epistemological difference between a 3D model of a Romanesque capital built to be viewed in a museum’s app and one that can be explored on GIS about the medieval iconography: both projects have to do with history and need historical skills, but only the second originates from and directly answers to a historical question.

Likewise, if we look at the wide sector of the digital editions of texts, it is obvious that these publications always facilitate historical research, but there is a clear difference between an edition built to study linguistic data and one that highlights the elements of greatest historical relevance. In order to recognise Digital History within the current Italian Digital Humanities, a painful simplification of complexity was nonetheless necessary: I chose identify some macro areas for the historical papers, based on a few general categories, taking into account the main question at the basis of the research. Therefore, the category ‘historical disciplines’ has been applied only to the abstracts where the proximity to the historical problems was explicit and predominant (History, Art History, History of Literature, History of Science, Oral History, History of Ideas, History of Architecture), providing different labels for contributions dedicated to the field of Archives, Libraries, Bibliography and Artistic-Architectural Heritage. As for the Disciplines of the Text, they were considered both collectively and by distinguishing them among Publishing, Philology, Literature and Linguistics (the digital edition of historical sources has been included in the ‘Philology’ label).

The outcome is in table 1:17

17 Please note that an abstract can have from one to three labels and the ‘education’ label for AIUCD2019 was expunged as the conference was dedicated to Pedagogy, Teaching, and Research in the Age of Digital Humanities.

|

AIUCD 2018 |

AIUCD 2019 |

AIUCD 2020 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

abstracts |

52 |

% |

57 |

% |

43 |

% |

|

Digital humanities |

2 |

3,85 |

15 |

26,32 |

2 |

4,65 |

|

Cultural heritage |

14 |

26,92 |

13 |

22,81 |

10 |

23,26 |

|

Publishing |

1 |

1,92 |

2 |

3,51 |

0 |

0,00 |

|

Philology |

11 |

21,15 |

5 |

8,77 |

8 |

18,60 |

|

Philosophy |

0 |

0,00 |

2 |

3,51 |

0 |

0,00 |

|

Geography |

1 |

1,92 |

0 |

0,00 |

0 |

0,00 |

|

Literature |

6 |

11,54 |

9 |

15,79 |

4 |

9,30 |

|

Linguistic |

7 |

13,46 |

6 |

10,53 |

12 |

27,91 |

|

Historical disciplines |

12 |

23,08 |

8 |

14,04 |

7 |

16,28 |

In table 2, the presence of History was isolated among the macro sector of the Disciplines of the Text and the remaining branches of the Digital Humanities.

|

AIUCD 2018 |

AIUCD 2019 |

AIUCD 2020 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

abstracts |

52 |

% |

57 |

% |

43 |

% |

|

|

Disciplines of the text |

25 |

48,08 |

22 |

38,60 |

24 |

55,81 |

|

|

Cultural heritage |

14 |

26,92 |

13 |

22,81 |

10 |

23,26 |

|

|

Historical disciplines |

12 |

23,08 |

8 |

14,04 |

7 |

16,28 |

|

|

History |

4 |

7,69 |

4 |

7,02 |

3 |

6,98 |

|

|

Other |

3 |

5,77 |

2 |

3,51 |

2 |

4,65 |

|

The three meetings, albeit with some understandable oscillations, offer a fairly stable picture of Italian Digital Humanities, where the projects belonging to the Disciplines of the Text and to the management of the digital (digitised or born digital) cultural heritage are dominant. The world of historians in a broad sense promotes an average of 15-17% of the projects, a percentage that decreases considerably if we consider History – in a narrower sense – as a discipline different from other specialised sectors, which obviously developed peculiar methodologies, such as History of Architecture or History of Art.

A closer look at the historical proposals allows us to better recognise the digital humanities tools and methods that have been used in research (overall analysis for the three-year period 2018-2019). In evaluating table 3, consider that, even here, I had to simplify by combining the multiple tools developed in these recent years.

|

History |

History of Arts (Music, Visual Arts) |

History of Culture (Literature, Science, Ideas) |

History of Architecture |

Archaeology |

TOT |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Database |

6 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

12 |

|

GIS |

4 |

1 |

5 |

|||

|

Web/social |

3 |

2 |

5 |

|||

|

Social network analisys |

2 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

||

|

Multimedia |

1 |

1 |

2 |

|||

|

Text encoding |

1 |

1 |

2 |

|||

|

Corpora |

1 |

1 |

2 |

|||

|

Semantic web |

1 |

1 |

2 |

|||

|

3D modeling |

2 |

2 |

||||

|

Digital libraries |

1 |

1 |

2 |

|||

|

Distant reading |

1 |

1 |

||||

|

Data visualization |

1 |

1 |

Apart from the anomalous data of archaeology, which is in fact not represented in the AIUCD activity and therefore cannot be assessed from the point of view of its relationship with digital humanities through the considered sources, the data clearly show important the use of databases is for Digital History and, in particular, GIS. The relationship between history and geography has always been obviously very close, but we can surely say that the GIS has provided the historical, archaeological and architectural disciplines with a key tool that can produce a qualitative leap in cataloguing, analysing, comparing, and visualising historical data. GIS is obviously used in many other fields, but in this analysis, it appears as the main tool in historical projects. This data is certainly not new: see, for example, Francesca Bocchi’s pioneering research in Bologna.18 It also represents a useful reference for any plans to extend the training of historians in the field of the digital humanities.

Then, we cannot overlook the data about the web, which essentially concerns the publication of research outcomes for a wider public, with the contextual use of social networks and multimedia communication formats. Here too the data is not surprising and has a logical explanation: for historians the relationship with their ‘audience’ is fundamental, to a greater extent than in other human sciences. As we have already seen in the analysis on the AIPH books of abstracts, digital history often tends to naturally become digital public history, both because the historical interpretation has a very close and complex link with the public narrative of history,19 and because the birth of the web and the social networks has created new historiographic practices open to direct participation of the users. Another phenomenon shown in the table is the distance that still divides historians from the tools that have long been developed and used by linguists, philologists and scholars of literature. All digital humanities essays rightly praise father Busa and identify the Computational Linguistics as the starting point of the new course of the human sciences since the Seventies, but the text encoding techniques, the study of the concordances, and the natural language processing tools are still very far from the practice of the historians, as well as the semantic web and the social networks analysis.

19 By public narrative of the History we obviously do not mean only the History conveyed and promoted by the institutions, but also that produced by the communities, the groups, the movements.

This distance is well exemplified by looking at some ongoing projects reported by the AIUCD website, which, in the vast majority of cases, provide the historian with resources to explore a certain phenomenon, but are not promoted by historians.20

20 http://www.aiucd.it/progetti/. It would be a useful and interesting service if the digital humanities projects always included a section that would make the reader aware of the use that is being made of the resource itself.

The Vespasiano da Bisticci’s Letters edited by Francesca Tomasi21 is an excellent example of a digital scholarly edition of a fifteenth century Florentine copyist, accompanied by several philological orientation tools (authorities, synoptic table, philological notes, description of the witnesses) and other information. The historical data, however, are offered only through linked data from the corresponding DBpedia entries and no further information on the historical figure, the period or the historical context can be found on the site. To avoid misunderstandings, I evaluate the edition of Vespasiano da Bisticci’s Letters as one of the best Italian digital humanities projects currently active: I simply recognise that this source is hardly useful for historical research, not made for and nor thought by historians. A similar statement, albeit with the necessary distinctions, can be done – looking at the AIUCD showcase – for DanteSources, Digital Ramusio, Epistolario Alcide de Gasperi, Idilli di Giacomo Leopardi, Petrarchive, La dama boba, Last Letters and PoLet500.

The remaining projects on the site showcase are collections of resources that could be filed in the macro-category of the ‘Cultural Heritage’ collection: digital libraries of historical textual or material or hybrid sources, equipped with a rich set of metadata and searchable through a dedicated engine. These projects include the DASI (Digital Archive for the Study of pre-Islamic Arabian Inscriptions), the CPhCl (Catalogus Philologorum Classicorum), the Digital Library of Family Books or The Uffizi Digitization Project with the 3D collection of the Greco-Roman sculptures of the Uffizi, Palazzo Pitti and the Boboli Gardens museums. These are essentially digital libraries, organised repositories of objects related to the cultural heritage (therefore valuable resources for the historian), normally built without the presence of a historian on the team and – apart from The Uffizi Digitization Project – made to answer to linguistic/literary questions. The only exception in this panorama is Colonizzazioni interne e migrazioni (Inner colonizations and migrations),22 a digital history project that collects, catalogues and geolocates the projects of colonisation promoted by the European chancelleries between the 16th and 18th centuries by involving foreign settlers. Also, Colonizzazioni interne e migrazioni offers a repertoire of resources, but it gives priority, compared to the direct consultation of primary sources, to materials half-processed or processed to answer historical questions.

22 https://storia.dh.unica.it/colonizzazioninterne/about by Giampaolo Salice. Exceptions also include the Codice Pelavicino Digital Edition, edited by myself: an edition in which the text encoding looks with particular attention at historical data and the web interface is designed for the collaboration with the public; it is not examined because it is still incomplete (http://pelavicino.labcd.unipi.it/).

4 A Strange Position

At least two sectors – Disciplines of the Text and Digital Libraries – touch on the strange position of Digital History in current historical research. Historians seem to have completely assigned the competence on the digital edition and the treatment of written sources of the Disciplines of the Text and the responsibility for the management of historical collections, corpora, archives and digital libraries to the professionals of the GLAM sector,23 who do not play an active role in designing platforms and survey tools. In these areas, History is practically everywhere, but used as parsley in the cooking: it seasons many dishes, but it does not hold a whole one.

23 Acronym for Galleries, Libraries, Archives and Museums.

This distance appears less wide in the Digital Public History field, where – as we know well by now – digital libraries rank third in the use of digital tools and methods, after the web and the social media; but that kind of projects are usually promoted by public historians who work in the GLAM world. So, the situation remains basically the same. The web – as we know well by now – provides a huge quantity and variety of content. It allows free access to primary and secondary sources that the users can freely collect, associate, annotate and elaborate in a personal or collective (community) reading. When a digital library not only allows for a good access to the sources, but favours their discovery and rediscovery, enhances certain contents, and brings a peculiar investigation path to the attention of the user in order to answer a collective need or because of its historical relevance, then we are in the field of the Digital Public History. It does not matter if the author is an archivist or an historian.

Among the best examples is the project Cartastorie of the Museum of the Historical Archive of the Banco di Napoli,24 born to enhance the enormous heritage kept in the folders of the ancient Neapolitan banks in perfect complementarity with the database and the digital services of the archives themselves: the Cartastorie, with its multimedia paths “respectful of the identity and specificities of the Archives” which address “different audiences in different ways by creating for them an experience of wonder and amazement that is not separated from sense and meaning” is a fine example of intermediation of an archival heritage with the aims and methods of the public historian. This need to reason about a new intermediation, after the great disintermediation of the various web contents formats, comes from a world – the GLAM one – made by people who daily and steadily work on the sources of the historians’ work.

5 Digital Tools and Methods: An Educational Problem?

My analysis is mirrored in a recent book edited by Deborah Paci on Digital History, an interesting collection of essays that reflects on the ‘digital historical culture’ nowadays, presenting a panorama of the ongoing research (Paci 2019).

In the book, practices and research of Digital History are in fact distributed over four main sections or thematic areas, the same that emerged from our study: the communication of historical content at different levels of complexity and participation (web/social/storytelling), the historical-geographical databases (GIS), the archiving and information retrieval practices (our ‘cultural heritage’ label), and the use of computational linguistics and text processing methods in the historian’s job.

The relative weight of the 4 areas are more or less corresponding to that highlighted in our brief excursus, with a clear prevalence of the use of GIS and the methods and tools related to web communication; less featured are the information retrieval techniques and the computational methods for the analysis of the written sources. As regards the digital archives and libraries, the volume highlights that the search interface, the underlying data model, the quality of the digitization of the texts, and the navigation tools themselves are difficult to use by and therefore unsatisfactory for historians (Maxwell 2019); however, from this point of view, historians obviously pay for their self-isolation, because design teams of digital libraries are rarely involved in the building of those platforms and those who actually build them do not have a sufficient knowledge on information retrieval methods. As regards the Disciplines of the Text, the tools and methods for a semi-automatic analysis of a written source are now widespread, as are the techniques for the social network analysis in textual corpora, but these methods are very rarely used in the Italian historiography of the last 10 years.25 Likewise, the evolution of the methods to publish a good digital edition of historical sources has reached an extremely high level of quality, but in most cases, we see only philologists at work, with the consequent publication of excellent digital editions, where the historian often works traditionally. In the other two major areas – GIS and the web – the situation is much better, but only if we look at the relative weight of these large areas compared to all the methods that emerged from the world of the digital humanities, and not because of their relevance in the historical studies.

25 The essay about the software MACHIATO is meaningful for the understanding of Machiavelli’s diplomatic correspondence described nowadays still as a “potential” with all the “dangers” of a “militant” initiative (Manchio 2019, 207-26).

This ‘distance’ highlights a serious problem. A long time has passed since the first pioneering experiments in the field of the Digital History and skepticism has been growing ever since. It is no longer possible to carry out historical research without knowing the methods offered by the digital technologies in order to process information and – as Serge Noiret says – “we can hardly imagine separating historical research from the tools, practices and programs necessary to carry it out”. This, in fact, “is no longer a viable road” (2019, 12).26

26 A very old question already posed by Manfred Thaller (1985, 871-90) and Robert Rowland (1991, 693-720).

My analysis simply confirms a well-known problem, which in Italy has not been tackled seriously so far: the education of the historians in the use of digital tools required for his/her profession. There is an almost total absence of Digital Humanities courses and programmes in the bachelor and master’s courses of history in Italy. This has in fact put Digital History in an “out of the box” position and placed historical researchers in friction with the digitization of our whole society and everyday life.

The spread of the digital in every filed of our lives, combined with the lack of a suitable education, has pushed the historians to spontaneously – and therefore haphazardly – approach only the digital methods and tools perceived as immediately useful. As regards the varied and vast world of the web, this path has led to a partial digitization of the tradition, both for research and dissemination; with the exception, for the reasons already mentioned, of the digital public historians.

As far as GIS is concerned, the question is more complicated. The use of GIS in digital public history implies – if the tool is used only for the visualisation of historical data – the acquisition of specific skills. GIS requires a huge construction work of the data model, a wise design of the platform allowing for a dynamic visualisation, transparency on the methodological choices, and a detailed documentation to restrain the user’s disorientation in front of the search engine.27 It is clear that GIS is a really important tool for the historian as well as a demanding one: hence also the advantages of the application of GIS in digital history are confined to a small niche of users.

27 From this point of view an excellent example is Slave Voyages (https://www.slavevoyages.org) created by the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship, the University of California (Irvine and Santa Cruz), and the Harvard University Hutchins Center: the result of a three-year (2015-2018) work carried out by an interdisciplinary team of cartographers, computer scientists, historians, librarians and web designers through the collaboration of scholars from various European, African and American universities, Slave Voyages does not ‘only’ allow to explore and display in a unique dynamic multi-source dataset on the transatlantic travel of slaves, but offers a rich set of explanations of sources, data model and historical essays that help the research and the interpretation of the phenomenon.

If Italian universities continue to churn out historians unaware of the main methodological questions posed by the digital humanities and unable to master their main tools, the “out of the box” position of digital history is destined to consolidate, no matter how much interesting, useful, and methodologically valid work is carried out by these self-formed digital historians. Back in 2015 Serge Noiret said: “today the ‘digital’ part of the historian’s profession has become essential even when one does not think of practicing a new discipline such as ‘digital history’ within digital humanities, but of continuing traditional practices updating them” (2015, 267). However, this update never took place,28 and this took history away from academic historians, opened their profession to an extremely wide and varied range of people and institutions, and left the historians outside the process of developing new methods of analysis. The trend seems clear, and while not necessarily negative or worrying, it is a position that has serious consequences on the relationship among the university, society, and the job market.29 So far, nothing has been able to change this stand-off: not the pioneering works – now good practices after forty years of experimentation –, nor the articles that highlighted potential and problems, nor the research that explained the innovations brought by the digital tools. The only relevant countertrend signal could come, in my opinion, from the Public History movement and its inevitable digital component. Although there is ongoing resistance of the Italian academy to incorporate the main tools and methods of the Digital History, new scenarios could be opened in Italy for the digital historian if Public History adds these tools to the historian’s educational path.

28 Many international authors denounce this lack of evolution everywhere. For example, Toni Weller (2013) talks about the soft impact of the digital revolution on the pre-existing practices of historians and in continuity with their professional traditions. Technology has not led to a new discipline from which to move in order to solve epistemological problems that, without digital tools, could not even be thought of.

29 A short personal note: in 20 years of teaching in Pisa in the degree course in Digital Humanities, several of my students – with an ‘insufficient’ historical education but a good one in Digital Humanities – found good jobs in archives, museums, libraries and in research projects with relevant historical-cultural aim, while their colleagues from the degree courses in History or Cultural Heritage were struggling to find a job corresponding to their CV.

6 History (with the Digital) and the Problem of the Statements

My previous statement could run counter to those who make a distinction between Digital History and Digital Public History as well as between Digital History and ‘history with digital tools’. Serge Noiret says that it is important to define the respective areas, in order to better highlight the characteristics of the Digital History in the wide galaxy of the Digital Humanities: “digital history is not history with digital and it is no longer time of generalist fields and universal humanistic practices with digital”, and “the digital history that uses and dominates technologies always refers to specific cognitive practices of historians and of the historian’s job”. Consequently, Noiret differentiates between “research, teaching, communication of the outcome [of historical research] today necessarily linked to the digital” (i.e ‘history with digital tools’) and “digital history” strictly speaking (2019, 13). The latter is defined by Deborah Paci as “a research area that uses, in the scholarly field of historical disciplines, methodologies, computational tools and computer techniques aimed at automatic or semi-automatic data processing, which are displayed and given back to the scholar through quantitative analysis” (2019, 19).

Personally, I find the definition of Deborah Paci correct, but partial, because the wide and articulated range of complementary activities that leads the historian to be ‘digital’ does not necessarily involve quantitative analysis, but all application of digital technologies to historical research that are methodologically sound. To avoid misunderstandings, I do not think that consulting the MGH online, publishing one’s essay on academia.edu, creating a bibliography on Zotero or broadcasting a history conference on streaming channels makes a historian digital, but maybe all these things together in a unified and well set project would. However, the profession of historian includes a very wide range of activities, in which digital tools and methods have a relevant place even if they do not involve computational activities.

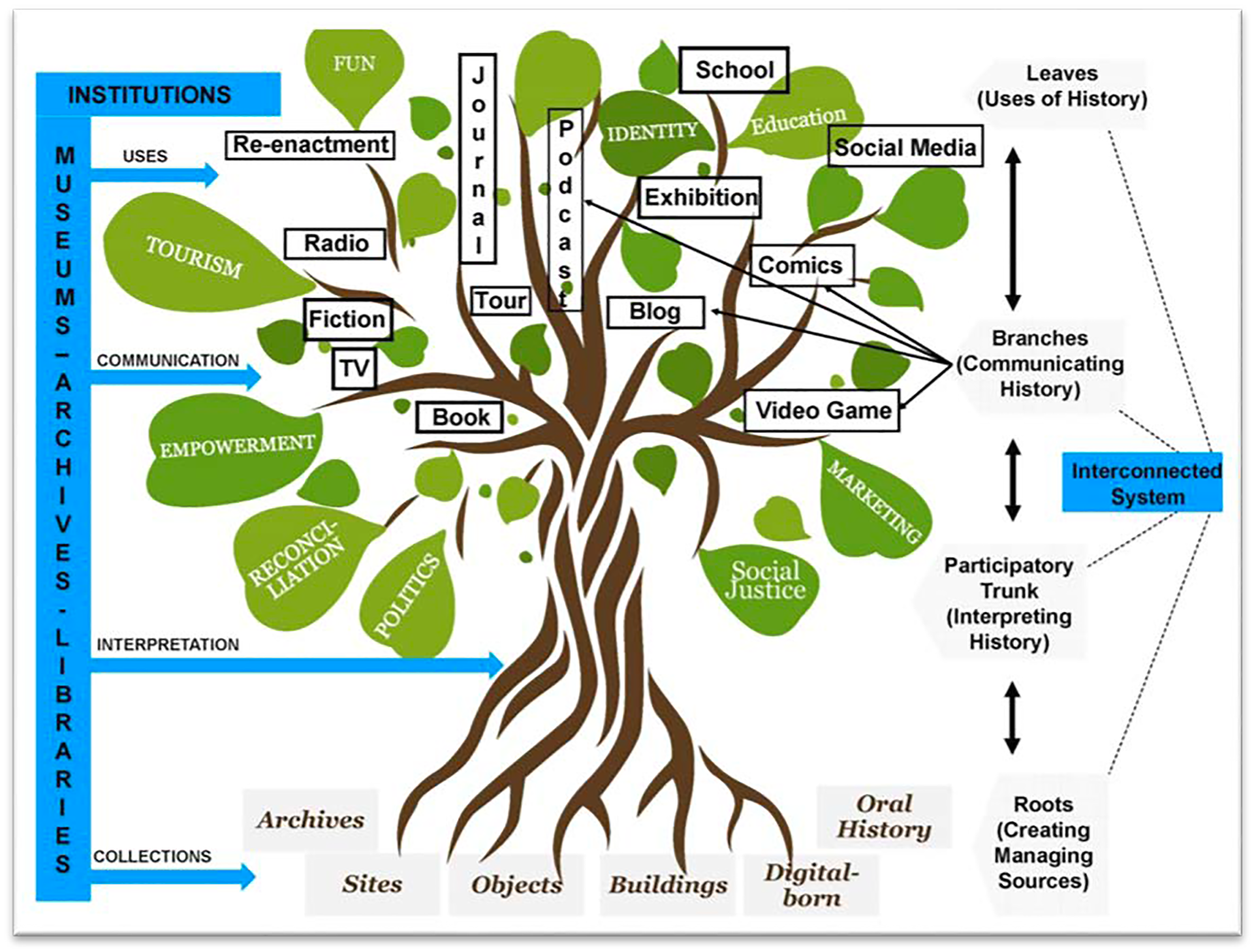

There are numerous fields in which digital technology enters the work of the historian without necessarily involving an “automatic or semi-automatic processing of data” or, at least, in which such treatment constitutes only a part of the process. The historian’s job is never confined to pure research, isolated from the environment, but lives on the deep interconnections that it has with the society which it communicates with. In the Public History Tree designed in 2019 by Thomas Cauvin these interconnections are expressed in an extremely effective way:

The tree is divided into four parts: the roots, the trunk, the branches and the leaves. Although they are different, these parts belong to a single system; one cannot exist without the other. While history has traditionally been defined as the rigorous and critical interpretation of primary sources (the trunk), public history is somewhat broader and includes four parts. The roots represent the creation and conservation of the sources; the trunk corresponds to the analysis and interpretation of the sources; the branches represent the diffusion of these interpretations; and the leaves are the multiple public uses of such interpretations. The more connected the parts, the richer and more coherent public history becomes. Furthermore, the structure is not linear; the uses (leaves) often have an impact on what we consider important to collect and store (roots). The public tree should not be seen as a pure linear process, but rather as an interconnected system. (Cauvin 2020, 20-1)

Figure 3 Public History Tree designed in 2019 by Thomas Cauvin

Cauvin’s tree schematically represents the Public History that is – in reality – a subset of History as a discipline. But I do not think that the differences – between Public History and History – are so macroscopic. Many believe that traditional history is localised in what we could define – in Cauvin’s tree – as the roots and the trunk, i.e. in the exegesis. This is characterised by the comparison of the sources, new interpretations, and communication of the outcomes only or mainly to the scholarly community. Even if for someone the tree of History may look more like a cypress – with reduced and codified interactions with the public – than like an oak or a willow, the interconnection between all parts remains strong and tight, because the historian must always use digital tools with a strong awareness, dominating and understanding their mediums. A digital historian working on the social media may certainly have to use techniques relating to the world of big data, but first of all, he/she must understand and dominate the medium itself, he/she should use social media to share information, interact with its audiences, collect the outcomes of this interaction and then make them flow back into new research. Making a digital edition of a historical source means not only knowing the ‘text encoding’ tools and methods, but also developing an appropriate encoding that allows the recovery and the comparison of historical information in order to allow for specific visualisations and analyses.30 The digital historian must also decide on ‘how’ the user can access information and what information to convey, because the impact of that decision will necessarily influence the individual’s historical interpretation of the source itself and that of the various communities (scholarly, local, specialised etc.).

30 For example, the variable spelling of common or proper names in medieval sources is a piece of information that is interesting in itself but that also requires a standardisation in order to search both variations (linguistic) and the meaning (history). In this regard, see also Thaller 2017.

Could I make ‘digital history’ without being aware of it? Could I build the website of my research not knowing the problems related to the concepts of original, copy, authenticity, counterfeiting, distribution, conservation, forgery that the digital inevitably places on the treatment of sources? Could I open the edition of a text to external comments and to a shared interpretation without being aware of the issues related to the shared authority on the web? If I do have all this knowledge, am I, or am I not a digital historian?

I know I will ruinously fall into a tautology, but I would simply modify the definition of Deborah Paci in this way: ‘digital history is a research area that employs, in the scholarly field of historical disciplines, methodologies, tools and IT techniques aimed at effectively answering historical questions’. Again Serge Noiret wonders “whether or not to continue referring to digital history today in the field – really generalist umbrella – of digital humanities” and then concludes that it is “better to translate digital humanities into individual disciplines, not to confuse tools, methods and questions”. The question is, in my opinion, ill posed. Certainly “as historians we need to create content” and have a clear “originality of our methods, tasks and final objectives in the digital field”, but we cannot do it using “digital tools different from those used by other humanists, who above all promote the exegesis, analysis and codification of the text” (Noiret 2019, 14).

There are no ‘different digital tools’. The digital historian – as we have seen – can better recognise which tools and methods belong where and which answer other scholarly questions. The historian should also use the tools of the Disciplines of the Text. Text analysis works really well and should still be used to answer to historical questions.

The return to the individual traditional disciplines would, in my humble opinion, be the real gravestone on the revolutionary flow of the digital turn for the humanistic field, which historians have often deserted. It is on the originality and specificity of the historical question – not on the tools – that the digital historian should insist on. Within the world of the digital humanities, above all, there should be a strong collaborative and interdisciplinary dimension with other digital humanists.

Several projects in the field of digital humanities are potentially relevant for the historians. These projects do not usually have historians in the team and are often incomplete and unsatisfactory. They offer large amounts of data and of resources that confuse the common reader and sometimes manage to answer only the questions raised by the creator of the resources.

Marco Tangheroni used to say that historical sources are like ‘well-behaved girls’, they only answer if you ask them. The answer – perhaps – lies precisely in thinking about the historical questions and in investigating without fear of interdisciplinary mixes. We must use all the available tools, update them, modify them, and adapt them to the questions themselves. This operation requires a radically new way of working as an interdisciplinary team. Academic historians are very reluctant to adopt this approach, but for the public (digital) historian, maybe, it is obligatory.

Bibliography

Allegrezza, S. (ed.) (2019). “Didattica e ricerca al tempo delle Digital Humanities”. AIUCD2019 - Book of Abstracts. http://amsacta.unibo.it/6361/.

Burgio, E.; Simion, S. (a cura di) (2015). Giovanni Battista Ramusio. Dei viaggi di Messer Marco Polo. Edizione critica digitale progettata e coordinata da Eugenio Burgio, Marina Buzzoni, Antonella Ghersetti. Venezia: Edizioni Ca’ Foscari. http://virgo.unive.it/ecf-workflow/books/Ramusio/main/index.html.

Cauvin, T. (2018). “The Rise of Public History: An International Perspective”. Historia Crítica, 68, 3-26. https://doi.org/10.7440/histcrit68.2018.01.

Cauvin, T. (2020). “Campo nuevo, prácticas viejas: promesas y desafíos de la historia pública = New Field, Old Practices: Promises and Challenges of Public History”. Hispania Nova. Primera Revista de Historia Contemporánea on-line en castellano. Segunda Época, 1 extra (7/5/2020), 7-51. https://doi.org/10.20318/hn.2020.5365.

DanteSources. Per una enciclopedia dantesca digitale (2016). https://dantesources.dantenetwork.it/.

Edizione digitale dell’Epistolario di Alcide De Gasperi. https://www.epistolariodegasperi.it/#/.

Gil, T. (2015). “Storici e informatica: l’uso dei database (1968-2013)”. Memoria e ricerca, 50, 161-78. https://doi.org/10.3280/mer2015-050010.

Gil, T. (2019). “L’utilizzo dei database da parte degli storici: storiografia e dibattito attuale”. Allegrezza, S. (a cura di), AIUCD2019 - Book of Abstracts. Udine, 2019, 177-81.

Italia, Paola (a cura di). Idilli di Giacomo Leopardi. http://leopardi.ecdosys.org/it/Home/.

Manchio C. (2019). “Per un’analisi 2.0 della corrispondenza machiavelliana”. Paci 2019, 207-26.

Marras et al. (a cura di) (2020). La svolta inevitabile: sfide e prospettive per l’Informatica Umanistica. Milano: Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, 2020. http://amsacta.unibo.it/6316/.

Maxwell, A. (2019). “Le ricerche storiche sugli archivi digitali. Alcune note di ricerca”. Paci 2019, 161-74.

Noiret, S. (2009). “‘Public History’ e ‘storia pubblica’ nella rete”. Ricerche storiche, XXXIX/2-3 (2009), 275-327.

Noiret, S. (2011). “‘Public History’: una disciplina fantasma?”. Memoria e Ricerca, 37, 10-35.

Noiret, S. (2015). “Storia contemporanea digitale”. Minuti, R. (a cura di), Il web e gli studi storici. Guida critica all’uso della rete. Roma: Carocci, 267-300.

Noiret, S. (2019). “Prefazione. Homo digitalis”. Paci 2019, 9-18.

Paci, D. (2019). La storia in digitale. Teorie e metodologie. Milano: Edizioni Unicopli.

PoLet500. http://www.polet500.it.

Rowland, R. (1991). “L’informatica e il mestiere dello storico”. Quaderni Storici, XXVI, 78, 693-720.

Santarelli, D. (a cura di) (2019). Invito alla storia: terza conferenza italiana di Public History (Santa Maria Capua a Vetere e Caserta, 24-28 giugno 2018, AIPH, 2020). https://aiph.hypotheses.org/9076.

Salvatori, E.; Privitera, C. (a cura di) (2018). Metti la storia al lavoro: seconda conferenza italiana di Public History (Pisa, 11-15 giugno 2018). https://aiph.hypotheses.org/7389.

Salvatori, E. (2018). “Per un’analisi delle pratiche di Public History”. Salvatori, Privitera 2018, abstract 47.

Spampinato, D. (2018). “Patrimoni culturali nell’era digitale”. AIUCD2018 - Book of Abstracts. http://amsacta.unibo.it/5997/.

Storey, H.W.; Walsh, J.A.; Magni, I. (eds). An Edition of Petrarch’s Songbook Rerum vulgarium fragmenta. http://dcl.slis.indiana.edu/petrarchive/.

Tammaro, A.M. (2005). “Che cos’è una biblioteca digitale?”. DigItalia, 1. http://digitalia.sbn.it/article/view/325/215.

Thaller, M. (1985). “Possiamo permetterci di usare il computer? Possiamo permetterci di non usarlo?”. Quaderni Storici, XX, 60, 871-90.

Thaller, M. (1993). “Historical Information Science: Is There Such a Thing? New Comments on an Old Idea”. Historical Social Research Supplement, 29, 60-286.

Thaller, M. (2017). “Between the Chairs. An Interdisciplinary Career”. Historical Social Research Supplement, 29, 7-109. http://doi.org/10.12759/hsr.suppl.29.2017.7-109.

Tomasi, F. (2013). Vespasiano Da Bisticci’s Letters. A Semantic Digital Edition. http://doi.org/10.6092/unibo/vespasianodabisticciletters.

Vega, Lope de (2015). La dama boba: edición crítica y archivo digital. Bajo la dirección de Marco Presotto y con la colaboración de Sònia Boadas, Eugenio Maggi y Aurèlia Pessarrodona. PROLOPE, Barcelona; Alma Mater Studiorum, Università di Bologna, CRR-MM, Bologna.

Vitali, G.P. Last Letters from the World Wars: Forming Italian Language, Identity and Memory in Texts of Conflict. http://www.ultimelettere.it/LastLetters/people/.

Weller, T. (2013). History in the Digital Age. Routledge.