Officina di IG XIV2 – Civic Inscriptions from Hellenistic Kephaloidion

Abstract This study delves into the only three Hellenistic civic inscriptions of Kephaloidion (modern Cefalù), a secondary harbour in northern Sicily. The inscriptions, despite their fragmentary nature, reveal unique linguistic and historical features that align with regional trends, including the role of civic officials. Two of these inscriptions are rather early examples of civic epigraphy in Kephaloidion, and appear to be dedications of local officials with some unique features. The third one, a statue base honouring a Roman individual of the gens Domitia, may be one of the oldest examples of honorific epigraphy for a provincial governor in Sicily, if identified with L. Domitius Ahenobarbus (pr. 97 BC).

Keywords Kephaloidion. Hellenistic Sicily. Civic epigraphy. Local officials. Provincial governors.

The city of Kephaloidion (modern Cefalù) was during the Hellenistic period a secondary harbour on the northern shores of Sicily, almost midway between the bigger cities of Thermai to the west and Halaesa to the east. With just seven Hellenistic inscriptions currently recorded in I.Sicily,1 its epigraphic yield has been modest, partly due to the low quality of local stone. Out of those seven inscriptions, three fragmentary pieces are reviewed in this paper, the only ones that can be categorised as public. I will argue that these three inscriptions are of major interest for the history of the city and of Sicily as a whole, as they combine elements that can be contextualized in the regional trends (both Sicilian and specifically from its northern coast) with certain original linguistic or historical features that make them remarkable. The paper offers reinterpretations for two of those three inscriptions.

am very grateful to Jonathan Prag and Marcus Chin, who have helped me in the process of writing this paper, and to the editors and two reviewers of Axon for their comments and corrections, which have improved it considerably. I am grateful to the Diocesi di Cefalù and Don Domenico Messina, who kindly permitted me access to the inscription located in the tower of the Cathedral of Cefalù and allowed the publication of photographs.

1 As of 25 October 2024. All seven are in Greek and, apart from the three civic inscriptions that this paper reviews, there are four of funerary typology: IG XIV 351 = ISic001173; SEG XXXIV, 949 = ISic002830; SEG XXXVI, 847 = ISic002952; SEG LVII, 877 = ISic002951.

1 Hellenistic Kephaloidion

The city of Kephaloidion (Cephaloedium in Latin) seldom appears in literary sources. The very first occurrence is in 396,2 amid a brutal war between Carthage and Syracuse and Himilco’s campaign against the latter and Messana in which the ‘fortress of Kephaloidion’ (τὸ Κεφαλοίδιον φρούριον) appears, alongside Himera, on good terms with the Punic general. Dionysius subsequently punished that alignment by taking the city.3 Archaeological elements confirm the creation of a walled settlement in this phase, when it even started minting coin, thus indicating a higher status than a mere φρούριον.4 In 307, another Syracusan army, en route from Thermai, captured the city, this time led by Agathocles, who put it under the command of Leptines as ἐπιμελητής. In fact, Agathocles offered next year to abandon the government of Syracuse in exchange of rule over Thermai and Kephaloidion.5 These episodes suggest a close link of the city with the nearby Himeraean/Thermitan community: Himilco obtained the friendship of both sites at the same time, whereas Agathocles’ seizure happened immediately after securing an alliance with Thermai.

2 Unless otherwise stated, all the dates are BC.

3 Diod. 14.56.2; 14.78.7.

4 Jenkins 1975; Cutroni Tusa, Tullio 1987.

5 Diod. 20.56.3; 20.77.3.

Diodorus’ last allusion to the city corresponds to 254, during the Roman campaign that conquered it together with Panormos and, shortly afterwards, most of the surrounding region.6 Subsequent references to Kephaloidion are scarce, and describe it as a second level town (πόλισμα in Strabo, oppidum in Pliny).7 Its ridged hinterland probably hindered agrarian productivity and, in fact, fishing was a significant component of the local economy,8 although the area was affected by tithers’ abuses under Verres’ governorship.9

6 Diod. 23.18.3.

7 Str. 6.2.1; Plin. Nat. 3.90; Sil. Pun. 14.252.

8 Ath. 7.302a. Tunny was particularly famous.

9 Cic. 2 Verr. 3.103; 172. See also Cic. 2 Verr. 2.128.

2 Civic Inscriptions from Kephaloidion

Hellenistic epigraphic material from Kephaloidion is equally scant, and public texts amount only to three. For centuries, a single inscription first published by Torremuzza in the eighteenth century was known, which was then present in the local bishopric archive and is now unfortunately lost. Kaibel offered both Torremuzza’s reading and his own interpretation:10

10 IG XIV 349 = ISic001171. For the original publication, Castelli 1784, Clas. I, no. 13.

|

………….. |

[ὁ δεῖνα τοῦ δεῖνα] |

|

ΤΟΥΠΟΛΥ...ΝΟΥ |

τοῦ Πολυ[ξέ]νου |

|

ΚΑΙΟΙΑΛΛΟΙΠΟΛΙ |

καὶ οἱ ἀλ[ειφόμενοι] |

|

ΗΡΑΚΛΕΙ |

Ἡρακλεῖ |

It was not until the early 1980s that new material was added to the city’s corpus. Following restoration works in the cathedral of Cefalù, a catalogue of the heritage held in the building and exposed in an exhibition was undertaken, which included two Hellenistic inscriptions unearthed during the conservation process. One of them was a sandstone block reused in the building and found under the base of the main apse’s southern edge, with the written side facing the nave. Due to the placement of the stone, which formed part of the architectonic structure, it was impossible at the time to extract it, so it was again covered under the floor following the restoration of the temple, where it remains, hidden to the public. According to Manni Piraino, the text reads as follows:11

11 Manni Piraino 1985, 145-7. For her previous reading, SEG XXXVI, 846 = ISic003090; Manni Piraino 1982, 64.

[— — — — — — — — —]

καὶ οἱ ἄλλοι πολ̣[ῖται?]

γραμματε[ὺς]

Γόργος Δωρ[ίδα?]

The second Greek inscription was reused in a wall outside the cathedral and could be recovered. It is currently inside the church, on the stairs of the southern bell tower, where it is accessible to the public.12 Carved on limestone with lumachelle, a locally widespread variety present in the local Hellenistic funerary inscriptions, buildings or the urban pavement, the text is now only visible with difficulty due to its imperfect craving and the irregular colour and surface of the material. Nevertheless, it became clear from the beginning that it contained the left part of an honorific Hellenistic text dedicated by the Kephaloiditan assembly (δᾶμος, albeit restored, appears evident) to a Roman individual, tentatively identified by Manni Piraino as a member of the gens Domitia:

12 Manni Piraino 1985, 147-9, with a preliminary reading in Manni Piraino 1982, 63-4; SEG XXXXVI, 845 = ISic003089. Tullio 2009, 669.

ὁ δᾶμο[ς τῶν Κεφαλοιδιτᾶν]

Λεύκιον ❦ Δο[μίτιον?...]

Γναΐου ❦ υἱωνο[ν…]

εὐνοίας ἕνεκα

In this paper, I shall propose that the two inscriptions recovered in the cathedral of Cefalù offer insights into the administrative and political life of ancient Kephaloidion. After physically analysing the piece, I additionally propose a new reading and further development for the second inscription.

3 IG XIV 349 and SEG XXXVI, 846: καὶ οἱ ἄλλοι πολῖται

The first of the inscriptions from the cathedral is also fragmentary, as only the bottom lines survive, with further loss in the right edge. It seems that little is missing on the right side, but the damage in the upper part is unfortunately impossible to assess. The expression καὶ οἱ ἄλλοι πολ[ῖται] in the first extant line suggests that a personal name existed in the preceding, likely with its patronym and perhaps even additional name or demotic adscription (which, if long enough, may have actually occupied two lines). Some parallels may be drawn from the last line, Γόργος Δωρ[… The name Γόργος is a well-attested name in Sicily, and even another individual linked to Hellenistic Kephaloidion bears it.13 Manni Piraino interpreted the latter word as Δωρίδα, although she did not justify her choice. Δωρ is most probably the beginning of the patronym rather than any other element. Given the apparently little space lost on the right, the patronym cannot have been too long, but parallels that fit are scarce. Δωριέως or Δωριῶς, genitive forms of Δωριεύς, a name linked to Sicily only by the campaigns of the homonym Spartan prince ca. 500, is not elsewhere epigraphically attested in the island, and the name Δωρικός (gen. Δωρικού) is only attested in fifth century Syracuse. Δωρόθεος, more broadly present in the island, seems too long to fit in the gap.14

13 LGPN IIIa s.v. “Γόργος”, 23-31. A stele from Demetrias in Thessaly reads Γόργος Διογνήτου Κεφαλωιδίτης (Thess. Mnem. no. 158 = Arvanitopoulos 1909, 408-9).

14 Hdt. 5.43-8; Diod. 4.23.3; Paus. 3.16.4-5b (Δωριεύς, see also CIL X, 7092 = ISic000374); Diod. 14.7.7 (Δωρικός). The name Δωρόθεος is present in Solous (IG XIV 312 = ISic001131), Thermae (IG XIV 313 = ISic001132), Halaesa (SEG LIX, 1100 = ISic030277) and Syracuse (Manganaro 1997, 313). See also I.Lipara no. 659 = ISic000806 (Δωροθέα) and I.Mus.Palermo no. 136 = ISic003495 (Δωρο--?--). Δωριῶς would be preferred as genitive form in Sicily (Mimbrera 2012, 237).

Several features denote the civic nature of the inscription. Firstly, there is the mention of the scribe (γραμματεύς), quite uncommon in Sicily. Apart from the list of the strategoi of Tauromenium and a bronze proxeny decree from Agrigentum, the few other instances of allusions to a γραμματεύς in Sicilian Hellenistic epigraphy correspond to votive texts. In Akrai, several collective dedications to Aphrodite mention the local γραμματεύς alongside the other magistrates.15 However, the most prominent parallel is found near Kephaloidion, in Thermai, in a dedication of the local ἀγορανόμοι to Aphrodite that alludes to the γραμματεύς at the very end of the text.16 Secondly, another rare characteristic is the inclusion of the locution καὶ οἱ ἄλλοι πολ[ῖται]. I completely agree with Manni Piraino’s restitution of the fragmentary text here, as I can find no other logical solution.17 This is an unusual clause in Sicilian epigraphy, with a single parallel found in Messina, which is nevertheless unanimously considered a forgery.18 In Greece and Asia, it often appears in honorary decrees to foreigners who receive citizenship, in isopoliteia treaties or in manumission decrees, in the clause bestowing equal civic rights to the local citizenry. These typologies do not apply to the inscription of Kephaloidion, much shorter than the rest. Manni Piraino considered it a votive text, alluding similarities with the piece from nearby Thermai also mentioning the γραμματεύς. Brugnone’s reconstruction of ἐκ τοῦ δήμου in the hardly readable third line of the Thermitan text, between the mentions to Aphrodite and the scribe, is suggestive and syntactically close to the inscription of Kephaloidion, but far from certain, in part because the Doric variant δᾶμος is universal in Sicily: the solution ἐκ τοῦ δάμω fits harder in the few visible traces of the stone.19 Anyway, the lack of a verb after καὶ οἱ ἄλλοι πολῖται similarly to other Eastern inscriptions makes the votive option probable. The most likely reconstruction would be the personal name of a local magistrate or civic official preceding the phrase καὶ οἱ ἄλλοι πολῖται, of which parallels exist at Delphi and Smyrna.20

15 IG XIV 208 (ISic001028); 209 (ISic001029); 211 (ISic001031); 212 (ISic001032). For Tauromenium, IG XIV 421 = ISic001246; for Agrigentum, IG XIV 952 = ISic030279.

16 IG XIV 313 = ISic001132.

17 It appears futile to interpret a magistracy here, as the only viable option, the politarchs (καὶ οἱ ἄλλοι πολιτάρχαι), is confined to Macedon and adjacent regions: Horsley 1994.

18 Korhonen 2018, 112-16 (correcting his previous position favouring its authenticity, I.Mus.Catania no. 236 = ISic003352). Kaibel already considered it a forgery inspired by Torremuzza’s publication of the inscription from Cefalù (see IG XIV 349).

19 IG XIV 313 = ISic001132. Brugnone 1974, 219-21. The reading is impracticable, but it appears that the line ends with –ου (personal appreciation from autopsy). Bechtel proposed ἐκ τοῦ ἰδίου (SGDI III no 3248).

20 FD III 4 no. 69 (οἱ άρχοντες καὶ οἱ ἄλλοι πολῖται); I.Smyrna no. 578 (οἱ στρατηγοί καὶ οἱ ἄλλοι πολῖται, although the first part is lost). See also IG XII.4.2 586 (Kos).

This solution can be supported by a parallel in Sicily, the famous Syracusan dossier with a letter of Hiero II followed by an oath of the civic body. In the second part of the inscription, which contains the oath by local officials and citizenry, scholars reconstruct the fragmentary text with the locution ὅρκιον βουλᾶς κα[ὶ στραταγῶν] καὶ τῶν ἄλλων [πολιτᾶν].21 However, the most resembling inscription including the expression καὶ οἱ ἄλλοι πολῖται in Sicily actually comes from Cefalù itself, and it is the first of the pieces mentioned in this paper.22 Torremuzza provided the first record of the mutilated text, which he found in the local bishopric archive in the middle of the eighteenth century. He read the third line as ΚΑΙ ΟΙ ΑΛΛΟΙ ΠΟΛΙ, which both himself and later Franz already developed as καὶ οἱ ἄλλοι πολῖ[ται] (CIG III, 5592). It was Kaibel who in his edition for the IG XIV, interpreted it as καὶ οἱ ἀλ[ειφόμενοι], linking it to local gymnastic culture, probably driven by the reference to Herakles and other instances of ἀλειφόμενοι in nearby Haluntium.23 However, the allusion to Herakles is far from unnatural in Kephaloidion, since he seems to have been the principal civic deity at that time. Local coinage commonly depicts him since the fourth century (when the city appears in literary sources), and sometimes alongside the legend ΕΚ ΚΕΦΑΛΟΙΔΙΟΥ or ΚΕΦΑΛΟΙΔΙΤΑΝ on the obverse, and ΗΡΑΚΛΕΙΩΤΑΝ on the reverse, which denotes the importance of his cult.24 Therefore, it seems more appropriate to interpret IG XIV, 349 as follows:

21 IG XIV 7, l.B 6-7 = ISic000827.

22 IG XIV 349 = ISic001171.

23 IG XIV 369 = ISic001192; IG XIV 370 = ISic001193.

24 CNS I, Kephaloidion nos 1-5, 10-13, 16-17. Consolo Langher 1961; Jenkins 1975, 93-9 (refuting previous theories that ascribed the coins to Heraclea Minoa).

[ὁ δεῖνα]

τοῦ Πολυ[ξέ?]νου

καὶ οἱ ἄλλοι πολῖ[ται]

Ἡρακλεῖ

The son of Polyxenos was probably a local magistrate or even the high priest of Herakles in Kephaloidion.25 Taking into account that Kaibel’s reading of the inscription was the only evidence so far to identify a gymnasium in Kephaloidion, it seems preferable to assume that the current documentation does not allow to support that theory.26 Similar characteristics can be inferred for the inscription of the cathedral, another dedication, maybe even to Herakles too due to its civic nature. In that case, the inscription would be roughly composed of six lines, of which the last three are almost complete. The first three lines would have contained the allusion to the god receiving the dedication (Herakles?),27 and perhaps the position of the main dedicator (either a local official or priest) and his name and patronym occupying two lines in total:

25 There was an important sacerdos maximus in the city at the time of Cicero: Cic. 2 Verr. 2.128.

26 Archaeological research has recently also relativized the presence of gymnasia in Sicily: Trümper 2018.

27 For other dedications in Sicily whose first element is the god who receives the offering, see IG XIV 431 = ISic001256 (Tauromenium); IG XIV 575 = ISic001394 (Centuripae); SEG XXXVII, 761 = ISic000770; I.Halaesa no. 4 = ISic003686 (Halaesa); SEG L, 1009 = ISic003109 (Catana); SEG XXXIV, 979 = ISic003009; SEG XLIV, 787 = ISic000634; Manganaro 1965, 186 = ISic003427 (Syracuse).

[Ἡρακλεῖ?]

[ὁ δεῖνα]

[τοῦ δεῖνα]

καὶ οἱ ἄλλοι πολ̣[ῖται]

γραμματε[ὺς] 5

Γόργος Δωρ[ιῶς?]

Manni Piraino’s dating between late fourth and early third century (which, based on its similarities with IG XIV 349, probably applies to the lost inscription too) is hard to ascertain as the evidence is rather superficial, although coherent with the few elements that can be put forward. The palaeographic features barely visible in the photographs are consistent with her proposal, which also coincides with the possible Syracusan influence that these inscriptions share. The expression καὶ οἱ ἄλλοι πολῖται is a local institutional expression not elsewhere attested in Sicily with the only exception of the Syracusan dossier, and even the choice of Herakles, the quintessential Dorian deity, as local divinity at an early stage (as shown in epigraphy and numismatics) could suggest a Dorian-Syracusan link. This influence may have originated from Syracuse’s intermittent control of the area during the fourth century: the victories over Carthage usually included the submission of Kephaloidion, and Agathocles even appointed an ἐπιμελητής for the city in 307. On the other hand, another option is the arrival of displaced populations from Heraclea Minoa following its seizure by the Punic army, as some deduce from fourth century coinage, although this theory is contested by certain scholars.28 In any case, the general political prominence of Syracuse in the island during this time explains that it inspired the administrative structures of the young Kephaloiditan city, whereas the adoption of the Sicilian Doric koina is a natural development.29

28 For the latter, Consolo Langher 1961. However, her theory is convincingly refuted by Jenkins 1975, 97.

29 Mimbrera 2012.

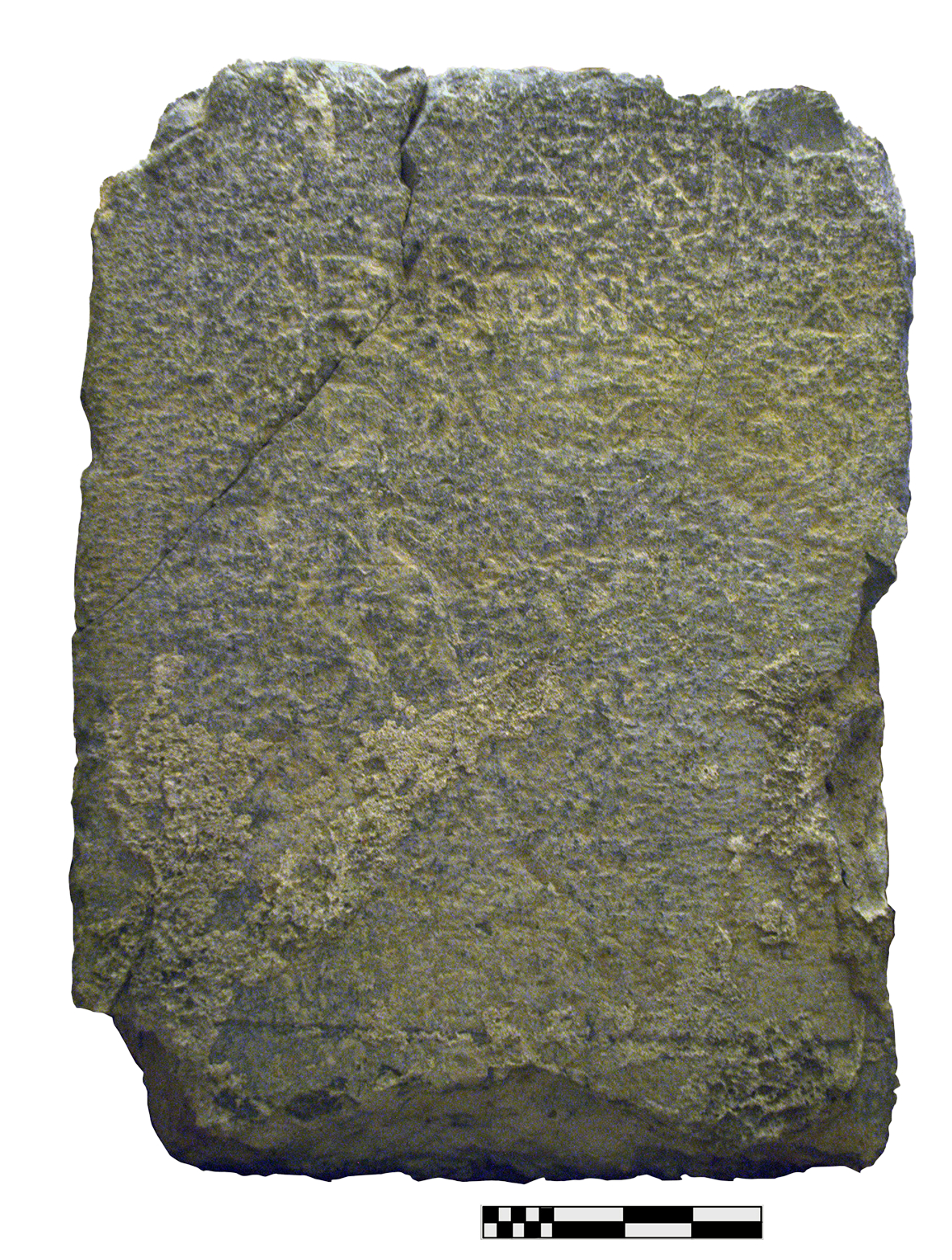

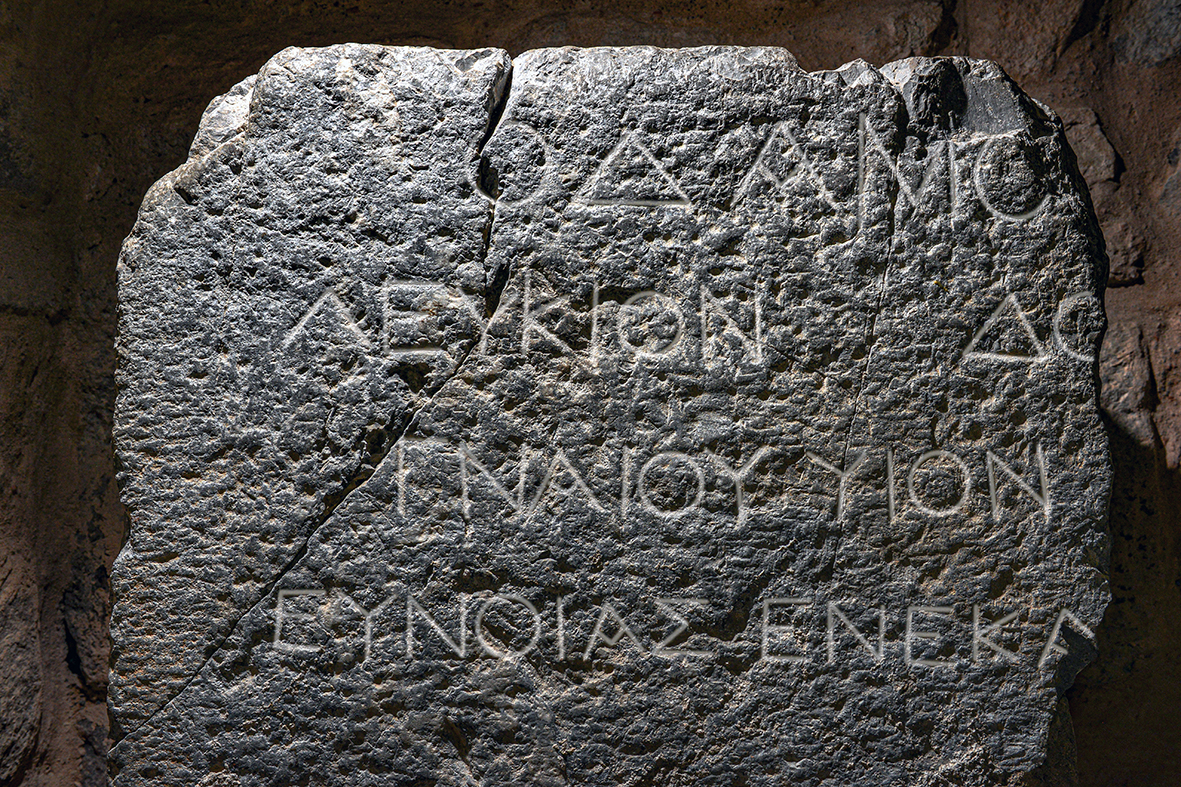

4 SEG XXXVI, 845: A New Reading and Interpretation

This is the only inscription that is nowadays physically accessible, located and visible on the stairs of the southern tower of Cefalù’s cathedral. Written on local limestone with lumachelle, both the roughness of the material and the rather superficial engraving complicate its reading. The stone is fragmentary, lacking its right end. It is 84 cm high, 60 cm wide and 25-42 cm deep, gradually decreasing from left to right and from top to bottom. The epigraphic space, composed of four lines, occupies only the top 38 cm. The script is quite irregular too, with signs shrinking every line, and even altering their sizes on each line. On the first line, letters are between 5.1-4.2 cm high, on the second 4-3.3 cm, on the third 4-3.4 cm, and on the fourth and last 3.6-3.2 cm. The use of spaces between words is also arbitrary: it is clear on the second line (where I propose a vacat), but almost imperceptible on the third and fourth, and completely absent on the first. The overall lack of uniformity makes the reconstruction of the lost portion difficult, as it is dangerous to assume that the text was centred. In any case, there is a much more pronounced justification to the left on the second and fourth lines, which could suggest they were accommodated to fit longer texts. My last autopsy produced the following transcription:

Ο ΔΑΜΟ[.]

ΛΕΥΚΙΟΝ vac. ΔΟ[…]

ΓΝΑΙΟΥ ΥΙΟΝ […]

ΕΥΝΟΙΑΣ ΕΝΕΚΑ […]

I find some differences from Manni Piraino’s original reading (see the interpretation and apparatus below).30 On the second and third lines, I did not find traces of hedera distinguens, a resource strange to Sicilian Hellenistic epigraphy, and the form of the upsilon, which Manni Piraino considered close to Ψ, appears closer to its usual shape. Although a deterioration of the material cannot be ruled out, it is also possible that the irregular surface of the rock misled the first readings, particularly given the oddity of the previously interpreted elements. Moreover, on the third line I read Γναίου υἱόν instead of υἱωνὸ[ν]. This correction eliminates another anomaly of the editio princeps, as there are no other instances of υἱωνός in Sicilian epigraphy to my knowledge. In both cases, the irregular surface of the rock, sometimes mistakable with engraving, probably misled Manni Piraino. A horizontal stripe below the letter leads to confusion between omicron and omega on the third line, but other inscriptions from Cefalù, similar in palaeography and material, depict a distinct omega, less circular and more slender, that do not match this case.31

30 Manni Piraino 1985, 147-9.

31 A notable example is IG XIV 351 (ISic001173, with photographs), reused in the left quoin of the Chiesa del Santissimo Sacramento, next to the cathedral of Cefalù itself. The material and lettering of this funerary inscription perfectly match those of SEG XXXVI, 845 = ISic000845.

For the first line, the Sicilian tradition of specifying the community that produces the decree (Manni Piraino thus developed τῶν Κεφαλοιδιτᾶν),32 albeit extended, is not universal. Hellenistic honorific inscriptions from Apollonia, Haluntium and Tyndaris (all three on the northern shore like Kephaloidion, although closer to Messina) lack the indication to the city.33 Since my impression is that the lost portion of the stone is smaller than Manni Piraino assumed, I favour the omission of the ethnic.

32 Following a widespread convention in Sicily: SEG XXXIV, 951 = ISic001660 (ὁ δᾶμος τῶν Λιλυβαιιτᾶν); IG XIV 434 = ISic001259; SEG XXXII, 936 = ISic003125; SEG XXXII, 937 = ISic003124 (ὁ δᾶμος τῶν Ταυρομενιτᾶν). The community is also specified in Phintias (IG XIV 256 = ISic001076), Segesta (IG XIV 288 = ISic001107; I.Segesta no. G4 = ISic001680; I.Segesta no. G5 = ISic001681), Halaesa (IG XIV 353 = ISic001175; IG XIV 356 = ISic001178; SEG XXXVII, 759 = ISic000800) and Syracuse (Syll.3 II no. 428 = ISic003331).

33 IG XIV 359 = ISic001181 (Apollonia); IG XIV 366 = ISic001189 (Haluntium); Manganaro 1965, 203 = ISic003348 (Tyndaris).

The second and third lines clearly contain the name of the honoured individual. The elements that survive (Λεύκιον … Γναίου υἱόν) point to a Roman man, and the first letters following the praenomen being ΔΟ, the only reasonable solution is that he was a member of the gens Domitia. I substantiate the reconstruction Λεύκιον Δομέτιον Γναίου υἱόν Αἰνόβαρβον, already considered by Manni Piraino in her second publication,34 on several arguments. The Ahenobarbi are the most prominent branch of the gens Domitia during the Republic, and Lucius and Gnaeus are the praenomina that their most renowned members bear. The spelling Δομέτιος is ubiquitous during the Hellenistic period, the variant Δομίτιος not arising until the Augustan age.35 A roughly similar pattern occurs with the form Αἰνόβαρβος instead of Ἀηνόβαρβος, which again emerges under Augustus’ reign.36 Some palaeographic features suggest a rather late Hellenistic period, with traces being more regular than in SEG XXXVI, 846, for instance in the shapes of the sigma, the gamma, and even the alpha or the mu, and in the size of the omicron (which is smaller in the previous case). These characteristics are coherent with local funerary inscriptions roughly dated to 200-50. 37 On the other hand, the form Λεύκιος indicates that the inscription from Cefalù is previous to Augustan era, when the alternative Λούκιος is found in Sicily.38 Early during the Julio-Claudian period the use of Latin for epigraphic dedications began to generalise too.39

34 Manni Piraino 1985, 149.

35 IG VII 413 (Oropos); IG IX.12.2 242 (Thyrreion); IG XII.6.1 351 (Samos); SEG XV, 254 (Olympia); I.Délos V no. 1763; I.Ephesos III no. 663; VI no. 2059; I.Knidos I no. 33; I.Smyrna no. 589; I.Iasos no. 612; Staatsverträge IV no. 706 v (Crete).

36 IG VII 413 (Oropos); IG IX.12.2 242 (Thyrreion); SEG XXIV, 580 (Amphipolis); I.Ephesos III no. 663. See, for the Augustan period, IG II2 4144; 4173 (Athens); I.Milet I,2 no. 12b; AE 1932 no. 6 (Chios).

37 IG XIV 351 = ISic001173; SEG XXXVI, 847 = ISic002952; SEG LVII, 877 = ISic002951. The pi and the rho are also dissimilar in the funerary inscriptions and in SEG XXXVI, 846, but they are unfortunately not present in the inscription discussed.

38 SEG XXVI, 1055 = ISic001418 (Agrigentum); SEG XXXIV, 953 (Lilybaeum); SEG XLII, 834 = ISic003001 (Buscemi).

39 The habit is evident in colonies and municipia (Prag 2002, 17; Korhonen 2011), but elsewhere too, and coincides with the general abandonment of Greek for such inscriptions: CIL X, 6992 = ISic000280 (Tauromenium); CIL X, 7501 = ISic003469 (Gaulos); EE VIII no. 708 = ISic003339 (Agathyrnum); I.Lipara no. 751 = ISic004267; I.Lipara no. 752 = ISic004268; I.Lipara no. 753 = ISic004269.

On the fourth and last line, one would expect nothing more than εὐνοίας ἕνεκα, but since the letters are smaller and the text is justified to the left, it rather seems that supplementary formulations followed. Manni Piraino’s proposed restoration (albeit in l. 3, since she considered the lost text to be larger), εὐεργέτην, is not coherent with the existent Sicilian documentation: although foreigners (including Roman magistrates) received that honour, it is only attested in decrees (often alongside proxeny). The statue bases for εὐεργέται honour exclusively local citizens, and usually in a later period.40 Actual parallels of formulae in Sicily accompanying εὐνοίας ἕνεκα include θεοῖς πᾶσι, τᾶς εἰς αὑτόν and καὶ εὐεργεσίας. Among these, the expression that accompanies εὐνοίας ἕνεκα most immediately is καὶ εὐεργεσίας, particularly in nearby Halaesa, and therefore I prudently consider it a likely continuation, even though other possibilities exist.41 Taking into account these corrections, I propose this interpretation:

40 Prag 2018, 120-1. For the proxeny and euergesia decrees, IG XIV 952 = ISic030279; IG XIV 954 = ISic030281 (Agrigentum); IG XIV 953 (Malta); IG XIV 12 = ISic000832; IG XIV 13 = ISic000833; SEG LX, 1015 = ISic002947; SEG LX, 1016 = ISic002948 (Syracuse). For the statue bases, IG XIV 273 = ISic001096; IG XIV 277 = ISic001097; SEG XXXIV, 951 = ISic001190 (Lilybaeum); BE 1953, 277 = ISic003348 (Tyndaris); and also IG XIV 316 = ISic001135 (Thermae); IG XIV 367 = ISic001190 (Haluntium).

41 For the epigraphic tradition in Halaesa, see Prestianni Giallombardo 2012 (particularly pp. 176-80, 185); Prag 2018, 120-5 (with further Sicilian context on honours). It is true that the most repeated wording is εὐνοίας καὶ εὐεργεσίας ἕνεκα, and that τᾶς εἰς αὑτόν is usually added too. IG XIV 354 = ISic001176; SEG XXXVII, 759 = ISic000800; SEG XXXVII, 760 = ISic000612; SEG LXII, 658 = ISic003351 (Halaesa); SEG XXXII, 936 = ISic003125 (Tauromenium). The overall impression is that locally distinct traditions existed: IG XIV 359 = ISic001181 (Apollonia). For the wording of honorific epigraphy in Hellenistic Sicily, Dimartino 2019, 198-9; Henzel 2022, 90-1.

Ὁ δᾶμο[ς]

Λεύκιον vac. Δο[μέτιον]

Γναίου υἱόν [Αἰνόβαρβον]

εὐνοίας ἕνεκα [καὶ εὐεργεσίας?]

Apparatus

Key MP1 = Manni Piraino 1982; MP2 = Manni Piraino 1985.

1. δᾶμο[ς τῶν Κεφαλοιδιτᾶν], MP1, MP2.

2. Hedera distinguens instead of vacat, MP2; ΔΟ̣, MP1; Δο[μίτιον Λευκίου υἱόν], MP2.

3. Hedera distinguens after Γναίου, MP1, MP2; υἱωνό[ν…], MP1; υἱωνό[ν Ἀηνόβαρβον εὐεργέτην], MP2.

Translation: “The People to Lucius Domitius [Ahenobarbus], son of Gnaeus, on account of his own good will [and benefaction?].”

Figure 1 Cathedral of Cefalù (staircase of the southern bell tower). Hellenistic honorific inscription (SEG XXXVI, 845 = ISic003089)

Figure 2 Detail of the upper part of the stone with the inscription honouring L. Domitius (SEG XXXVI, 845 = ISic003089)

Figure 3 Detail of the upper part of the stone with the inscription honouring L. Domitius (SEG XXXVI, 845 = ISic003089). Edited to enhance the reading

It is impossible to ascertain the context in which the inscription was erected, given our limited knowledge of the history of Kephaloidion. However, the present interpretation of the fragmentary inscription permits a possible identification of the honoured man, Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, with the consul of 94, who had previously been praetor and governor of Sicily, most probably in the year 97, in the aftermath of the Second Servile War. Of course, our list of Roman governors in Republican Sicily is patchy, but this is the only magistrate of the gens Domitia attested in the province during the Republic.42 His administration is largely unknown, apart from an anecdote concerning the execution of a hunter who breached the prohibition for slaves to bear weapons.43 Manni Piraino proposed an early dating for the inscription of Cefalù, in the early third century, but a later date is plausible (and even probable) on palaeographic and typology grounds, and ascribing it to ca. 97 is entirely reasonable. Epigraphic honours to Roman magistrates in Sicily sometimes explicit their position in the text, but this is far from a general practice. Since L. Domitius governed Sicily as a praetor, it is tempting to develop on the third line Γναίου υἱόν [στρατηγόν] instead of his cognomen, but the available record of other honoured Roman magistrates shows that the cognomen is universally mentioned, whereas often the office is not.44 Those ellipses may be the consequence of the honours being bestowed after leaving office, when allusions to a magistracy would be less justified.

42 Prag 2007. Broughton mentions a L. Domitius Cn. f., senator in 129 and whose career remains obscure (MRR II, 490). The only source that attests him is the SC de agro Pergameno (I.Smyrna no. 589, l. 15, 22-3; I.Adramyt. no. 18, l. 5-7; I.Ephesos III no. 975), whose dating (either 129 or 101) is polemic.

43 Cic. 2 Verr. 5.7; Val. Max. 6.3.5; Quint. Inst. 4.2.17. RE V.1, Domitius 26.

44 IG XIV 435 = ISic001260 (Tauromenium); SEG XXXVII, 760 = ISic000612; CIL X, 7459 = ISic000583 (Halaesa); SEG I, 418 (Rhegium). In the case of governors, the office is only mentioned in SEG LXII, 691 = ISic003419 (Soluntum, ἀντιστράταγος); SEG L, 1025 = ISic002947 (Syracuse, ανθύπατος); IG XIV 612 (Rhegium, στραταγὸς). For the epigraphic use of the offices, see Ferrary 2000, 349-50.

If the identification with L. Domitius (consul 94) were correct, this would be the earliest honorific inscription (arguably a statue base) for a Roman governor and magistrate by a Sicilian city, predating those erected in Tauromenium to C. Claudius Marcellus (governor in Sicily 79-78) and in Soluntum to Sex. Peducaeus (governor in 76-75).45 So far, the only inscription dated before is the Latin dedication of the Italicei in Halaesa to Lucius Cornelius Scipio, who was praetor in Sicily in 193. However, this is a lost and polemic source, and its reading is far from certain.46

45 IG XIV 435 = ISic001260; SEG LXII, 691 = ISic003419. It also predates G. Vergilius Balbus’ inscription in Halaesa (IG XIV 356 = ISic001178, he was propraetor of Sicily in ca. 60: Cic. Planc. 95-6; Schol. Bob. 87 Stangl). Caninius Niger’s inscription belongs to the late second or early first century (SEG XXXVII, 760 = ISic000612). The earliest epigraphic honour recorded to a Roman official is the proxeny decree for the ἐπιμελητής Tiberius Claudius of Antias in Entella in the aftermath of the First Punic War (SEG XXX, 1120 = ISic030297). For honours to Romans in Hellenistic Sicily, see Prag 2007, 254-5; Berrendonner 2007, 214-18; Henzel 2022, 91-2.

46 CIL X, 7459 = ISic000583. Gualtherus’ transcription actually reads SCHIZIAM or FIIZIVM instead of Scipionem, so an alternative interpretation is possible: Badian proposed L. Cornelius Sisenna (governor in 77, Cic. 2 Verr. 2.110): Badian 1967, 94 fn. 1.

It is impossible to ascertain the causes behind the erection of this statue, but some possibilities can be considered. Firstly, as already mentioned, Domitius’ activity in Sicily is for the most part obscure, but since he governed Sicily during a post-war period, he had multitude of occasions to favour local communities with their reconstruction. A notable parallel would be the mysterious Lucius Asyllius that Diodorus records around the same period, whose positive and charitable measures enabled the economic recovery of the province from the previous devastation.47 Secondly, it is possible that L. Domitius Ahenobarbus favoured the small city of Kephaloidion and that there was a special bond between the Roman and the community. One could interpret in this context the presence of members of the local elite belonging to the gens Domitia at the end of the first century.48 Thirdly, it is true that Sicilian cities erected plenty of statues for Verres so, even if they tore down most of them soon thereafter,49 it seems that provincials regularly honoured Roman officials regardless of them actually deserving it.

47 Diod. 37.8.1-4. Diodorus does not allude to honours received by Asyllius, but it seems likely that they existed given the popularity of his governorship among the Sicilians.

48 RPC I no. 634.

49 Cic. 2 Verr. 2.48-52; 2.114; 2.144; 2.154-61; 4.89. Berrendonner 2007, 214-18.

In any case, it makes chronological sense that Kephaloidion erected a statue for a Roman commander early in the first century, as it predates the earliest known datable parallels by only a few years (two decades at most), and it is geographically reasonable as well, since those parallels come from nearby cities of the northern shore like Halaesa and Soluntum. It also arises from the Verrines that the local élite had strong ties with the Roman ruling class.50 Kephaloidion was probably a secondary city within the economic and political range of Halaesa, a major centre of the northern coast of Sicily. Cicero once groups together Halaesa, Thermae, Cephaloedium, Amestratus, Tyndaris and Herbita, which may have collaborated in other ways, as observable in some inscriptions too: the sailors of Halaesa, Caleacte, Herbita and Amestratus erected the inscription for Caninius Niger in Halaesa, and the knights of those same cities alongside Kephaloidion raised a second dedication, unfortunately still unpublished.51 The city apparently shared an epigraphic culture with these poleis that included honouring Roman officials.

50 Cic. 2 Verr. 2.128. An aristocrat from Kephaloidion, Herodotus, was at Rome during the elections.

51 Cic. 2 Verr. 3.172; SEG XXXVII, 760 = ISic000612. Scibona 2009, 108. Collura has reached the same conclusion of regular collaboration (even symmachia) among these communities: Collura 2019, 49-50. It seems also that some honorific tendencies are particular to certain areas of Sicily (like the northern coast) and not to the whole province: Dimartino 2019, 214-15. Cic. 2 Verr. 3.103 also alludes to Tyndaris, Haluntium, Apollonia, Engyum and Capitium, all of them located on the northern coast of Sicily. Interestingly, Late Republican issues from Cephaloedium show the existence not only of the gens Domitia, but also of the gens Caninia (RPC I no. 635), which may be indicative of the importance of their administration half a century before.

5 Conclusions

Even if extremely reduced, the corpus of civic inscriptions of Hellenistic Kephaloidion offers an interesting representation of this small city during the period. The earliest two fragments can probably be contextualised in the early third century, when Syracusan institutional influence is a commonplace. The reading I propose for IG XIV 359, based now on clear parallels, excludes its association with the gymnasium, and rather points to a religious dedication of a local magistrate. SEG XXXVI, 845 can now be linked, albeit with caution, to a recognisable governor of Sicily, which would make Kephaloidion the site of the earliest extant honorific inscription for such an official in the province. This is coherent with other examples from the north coast, particularly from nearby Halaesa, a major economic centre in the late Hellenistic period. In conclusion, the analysed texts show that Kephaloidion was influenced by and participated in the epigraphic tendencies and trends of its neighbours.

Bibliography

AE = (1888-). L’Année épigraphique. Paris.

CIL = (1863-). Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum. Berlin.

CNS I = Calciati, R. (1983). Corpus Nummorum Siculorum: la monetazione di Bronzo, vol. I. Milan.

EE VIII = (1899). Ephemeris Epigraphica. Corporis Inscriptionum Latinarum Supplementum. Vol. VIII, Accedunt tabulae duae. Berlin.

FD III 4 = Colin, G. (1930). Fouilles de Delphes. Vol. III, Épigraphie. Fasc. 4, Monuments des Messéniens de Paul-Émile et de Prusias, vols. 2 et 3. Paris.

I.Adramyt. = Stauber, J. (1996). Die Bucht von Adramytteion. Bd. 2, Inschriften, literarische Testimonia, Münzen. Bonn.

I.Délos V = Roussel, P.; Launey, M. (éds) (1937). Inscriptions de Délos, vol. V. Paris.

I.Ephesos III = Engelmann, H.; Knibbe, D.; Merkelbach, R. (1980). Die Inschriften von Ephesos, Bd. III. Bonn. IGSK 13.

I.Ephesos VI = Merkelbach, R.; Nollé, J. (1980). Die Inschriften von Ephesos, Bd. VI. Bonn. IGSK 16.

IG II² = Kirchner, J. (ed.) (1940). Inscriptiones Graecae II et III: Inscriptiones Atticae Euclidis anno posteriores. Ed. altera. Berlin.

IG VII = Dittenberger, W. (1892). Inscriptiones Graecae. Vol. VII, Inscriptiones Megaridis, Oropiae, Boeotiae. Berlin.

IG IX.1².2 = Klaffenbach, G. (ed.) (1957). Inscriptiones Graecae. Vol. IX.1, Fasc. 2, Inscriptiones Acarnaniae. Ed. altera. Berlin.

IG XII.4.2 = Bosnakis, D.; Hallof, K. (2012). Inscriptiones Graecae. Vol. XII, Inscriptiones insularum maris Aegaei praeter Delum, 4. Inscriptiones Coi, Calymnae, Insularum Milesiarum. Pars II, Inscriptiones Coi insulae: catalogi, dedicationes, tituli honorarii, termini (nos. 424-1239). Berlin; Boston.

IG XII.6.1 = Hallof, K. (ed.) (2000). Inscriptiones Graecae. Vol. XII, Inscriptiones insularum maris Aegaei praeter Delum. Fasc. 6, Inscriptiones Chii et Sami cum Corassiis Icariaque. Pars 1, Inscriptiones Sami Insulae: Decreta, epistulae, sententiae, edicta imperatoria, leges, catalogi, tituli atheniensium, tituli honorarii, tituli operum publicorum, inscriptiones ararum. Berlin; New York.

IG XIV = Kaibel, G. (ed.) (1890). Inscriptiones Graecae. Vol. XIV, Inscriptiones Siciliae et Italiae, additis Galliae, Hispaniae, Britanniae, Germaniae inscriptionibus. Berlin.

I.Iasos = Blümel, W. (1985). Die Inschriften von Iasos. Bonn. IGSK 28 1/2.

I.Knidos I = Blümel, W. (Hrsg.) (1992). Die Inschriften von Knidos, vol. I. Bonn. IGSK 41.

I.Milet I,2 = Fredrich, C. (Hrsg.) (1908). Milet: Ergebnisse der Ausgrabungen und Untersuchungen seit dem Jahre 1899. Bd. 1,2: Das Rathaus von Milet. Berlin.

I.Mus.Palermo = Manni Piraino, M.T. (1973). Iscrizioni greche lapidarie del Museo di Palermo. Palermo.

I.Halaesa = Prag, J.R.W.; Tigano, G. (2018). Alesa Arconidea: il lapidarium. Palermo.

I.Lipara = Campagna,L. (2003). Meligunìs Lipára XII: Le iscrizioni lapidarie greche e latine delle isole eolie. Palermo.

I.Mus.Catania = Korhonen, K. (2004). Le iscrizioni del Museo Civico di Catania. Ekenäs.

I.Segesta = Ampolo, C.; Erdas, D. (2019). Inscriptiones Segestanae. Le iscrizioni greche e latine di Segesta. Pisa.

I.Smyrna II = Petzl, G. (Hrsg.) (1990). Die Inschriften von Smyrna II, Bde. 1 und 2. Bonn. IGSK 24 1/2.

ISic = Prag, J. (2017-). I.Sicily: Inscriptiones Siciliae. Oxford. http://sicily.classics.ox.ac.uk/inscriptions/.

LGPN IIIa = Fraser, P.M.; Matthews, E. (1997). A Lexicon of Greek Personal Names IIIa. Peloponnese, Western Greece, Sicily, and Magna Graecia. Oxford.

MRR = Broughton, T.R.S. (1951-52). Magistrates of the Roman Republic. 2 vols. New York.

RPC I = Burnett, A.; Amandry, M.; Ripollès, P.P. (edd.) (1992). Roman Provincial Coinage, vol. I. London.

SGDI = Collitz, H.; Bechtel, F. (1884-1915). Sammlung der griechischen Dialekt-Inschriften. Göttingen.

Staatsverträge IV = Errington, R.M. (2020). Die Staatsverträge des Altertums. Bd. 4, Die Verträge der griechisch-römischen Welt von ca. 200 v. Chr. bis zum Beginn der Kaiserzeit. München.

Syll.3 II = Dittenberger, W. (Hrsg.) (1917). Sylloge Inscriptionum Graecarum, Bd. II, 3. Ausg. Leipzig.

Arvanitopoulos, A.S. (1909). Thessalika Mnemeia, Athens.

Badian, E. (1967). “A.J.N. Wilson: Emigration from Italy in the Republican Age of Rome”. Gnomon, 39(1), 92-4.

Berrendonner, C. (2007). “Verrès, les cités, les statues et l’argent”. Dubouloz, J.; Pittia, S. (éds), La Sicile de Cicéron: Lectures des Verrines. Besançon, 205-27.

Brugnone, A. (1974). “Iscrizioni greche del museo civico di Termini Imerese”. Kokalos, 20, 218-64.

Castelli, Gabriele Lancillotto, principe di Torremuzza (1784). Siciliae et objacentium insularum veterum inscriptionum nova collectio prolegomenis et notis illustrata, et iterum cum emendationibus, & auctariis evulgata. Palermo.

Collura, F. (2019). I Nebrodi nell’antichità: Città Culture Paesaggio. Oxford.

Consolo Langher, S.N. (1961). “Gli Ήρακλειώται έκ Κεφαλοιδίον”. Kokalos, 7, 166-98.

Cutroni Tusa, A.; Tullio, A. (1987). “Cefalù”. Bibliografia topografica della colonizzazione greca in Italia e nelle Isole Tirreniche, 5, 209-21.

Dimartino, A. (2015). “L’epistola di Ierone II e l’orkion boulas (IG XIV, 7): un nuovo dossier epigrafico?”. Epigraphica, 77, 39-65.

Dimartino, A. (2019). “Epigrafia greca e pratiche onorarie in Sicilia durante l’età ellenistica e romana”. Trümper, M.; Adornato, G.; Lappi, T. (eds), Cityscapes of Hellensitic Sicily. Rome, 197-217.

Ferrary, J.L. (2000). “Les inscriptions du sanctuaire de Claros en l’honneur de Romains”. BCH, 124, 331-76. http://dx.doi.org/10.3406/bch.2000.7266.

Henzel, J.H. (2022). Honores inauditi. Ehrenstatuen in öffentlichen Räumen Siziliens vom Hellenismus bis in die Spätantike. Leiden.

Horsley, G.H.R. (1994). “The Politarchs in Macedonia, and Beyond”. MedArch, 7, 99-126.

Jenkins, G.K. (1975). “The Coinages of Enna, Galaria, Piakos, Imachara, Kephaloidion and Longane”. AIIN Suppl., 20, 77-103.

Korhonen, K. (2011). “Language and Identity in the Roman Colonies of Sicily”. Sweetman, R.J. (ed.), Roman Colonies in the First Century of Their Foundation. Oxford, 7-31.

Korhonen, K. (2018). “Quattro iscrizioni di interesse storico-religioso attribuite a Messina”. Linguarum Varietas, 7, 105-18.

Manganaro, G. (1965). “Ricerche di Antichità e di epigrafia siceliote”. Archeologia Classica, 17, 183-210.

Manganaro, G. (1997). “Nuove tavolette di piombo inscritte siceliote”. PP, 52, 306-48.

Manni Piraino, M.T. (1982). “Il materiale antico reimpiegato e rielaborato in età normanna – Iscrizioni greche”. Mostra di documenti e testimonianze figurative della basilica ruggeriana di Cefalù: materiali per la conoscenza storica e il restauro di una cattedrale. Palermo, 63-4.

Manni Piraino, M.T. (1985). “Iscrizioni greche del Duomo”.Bonacasa, N.; Tullio, A.; Bonacasa Carra, R.M.; Manni Piraino, M.T.; D’Angelo, F. La Basilica Cattedrale di Cefalù. Materiali per la conoscenza storica e il restauro 3. La ricerca Archeologica. Preesistenze e materiali riempiegati. Palermo, 145-9.

Mimbrera, S. (2012). “The Sicilian Doric Koina”. Tribulato, O. (ed.), Language and Linguistic Contact in Ancient Sicily. Cambridge, 223-50. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139248938.012.

Prag, J. (2002). “Epigraphy by Numbers: Latin and the Epigraphic Culture in Sicily”. Cooley, A.E. (ed.), Becoming Roman, Writing Latin?. Portsmouth, 15-31.

Prag, J. (2007a). “Ciceronian Sicily: The Epigraphic Dimension”. Dubouloz, J.; Pittia, S. (éd.), La Sicile de Cicéron : Lectures des Verrines. Besançon, 245-71.

Prag, J. (2007b). “Roman Magistrates in Sicily, 227-49 BC”. Dubouloz, J.; Pittia, S. (éds), La Sicile de Cicéron : Lectures des Verrines. Besançon, 287-310.

Prag, J. (2018). “A New Bronze Honorific Inscription from Halaesa, Sicily, in Two Copies”. JES, 1, 93-141.

Prestianni Giallombardo, A.M. (2012). “Spazio pubblico e memoria civica. Le epigrafi dall’agora di Alesa”. Ampolo, C. (a cura di), Agora greca e agorai di Sicilia. Pisa, 171-200.

Scibona, G. (2009). “Decreto sacerdotale per il conferimento della euerghesia a Nemenios in Halaesa”. Scibona, G.; Tigano, G. (a cura di), Alaisa-Halaesa. Scavi e ricerche (1970-2007). Messina, 97-112.

Trümper, M. (2018). “Gymnasia in Eastern Sicily of the Hellenistic and Roman Period”. Mania, U.; Trümper, M. (eds), Development of Gymnasia and Graeco-Roman Cityscapes. Berlin, 43-73.

Tullio, A. (2009). “Indagini archeologiche (2000-2001) nell’area della Basilica Cattedrale di Cefalù”. Kokalos, 47-48, 669-73.